Thus says the Lord,

“Preserve justice and do righteousness,

For My salvation is about to come

And My righteousness to be revealed.

“How blessed is the man who does this,

And the son of man who takes hold of it;

Who keeps from profaning the sabbath,

And keeps his hand from doing any evil.”

Let not the foreigner who has joined himself to the Lord say,

“The Lord will surely separate me from His people.”

Nor let the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.”For thus says the Lord,

“To the eunuchs who keep My sabbaths,

And choose what pleases Me,

And hold fast My covenant,

To them I will give in My house and within My walls a memorial,

And a name better than that of sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name which will not be cut off.

“Also the foreigner who join themselves to the Lord,

To minister to Him, and to love the name of the Lord,

To be His servants, every one who keeps from profaning the sabbath and holds fast My covenant;

Even those I will bring to My holy mountain

And make them joyful in My house of prayer.

Their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be acceptable on My altar; for My house will be called a house of prayer for all the peoples.”

The Lord God, who gathers the dispersed of Israel, declares,

“Yet others I will gather to them, to those already gathered.”–Isaiah 56:1-8 (NASB)

I made a comment in one of my recent blog posts that having rendered a simple, basic definition for living a life of holiness, what else should I write about? After all, once the path is before me, my only job is to walk the path, not write endless commentaries about it.

But somewhere in my comments, I also mentioned the need to address, among other things, certain sections of Isaiah 56, from which I quoted above. I have largely defined a life of holiness for a non-Jewish disciple of Rav Yeshua (Jesus Christ) apart from the vast majority of Jewish lifestyle and religious observance practices. To live a life of holiness and devotion to God, it is my opinion that we non-Jews have no obligation observe the traditional mitzvot associated with religious Jewish people.

But we encounter a few “problems” in the above-quoted passage from Isaiah. Even leaving out the sections that relate to “eunuchs,” “the foreigner” is not to consider himself (or herself) as being separated from His people (presumably Israel). Further, foreigners who join themselves to the Lord do so, in part, by not “profaning the sabbath” (otherwise translated as “guarding” the sabbath) and by holding fast to “My [God’s] covenant.”

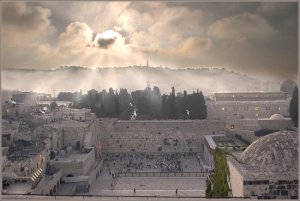

In addition, the foreigner will be joyful in Hashem’s house of prayer (the Temple) and it will be called “a house of prayer for all peoples,” which seems to indicate the people of every nation.

In addition, the foreigner will be joyful in Hashem’s house of prayer (the Temple) and it will be called “a house of prayer for all peoples,” which seems to indicate the people of every nation.

In doing some research for today’s “meditation,” I discovered I’ve written about the Book of Isaiah before.

That was a sweeping panorama of the entire book (click the link to read it all), but of Isaiah 56, I wrote only this:

Isaiah 56 is the first time in the entire sixty-six chapter book that says anything specifically about how the nations will serve God. I was wondering if the word “foreigner” in verse 3 might indicate “resident alien” and somehow distinguish between Gentile disciples of the Messiah and the rest of the nations, which could bolster the claim of some that these “foreigners” merge with national Israel, but these foreigners, also mentioned as such in verse 6, are contrasted with “the dispersed of Israel” referenced in verse 8.

And…

And the foreigners who join themselves to Hashem to serve Him and to love the Name of Hashem to become servants unto Him, all who guard the Sabbath against desecration, and grasp my covenant tightly…

–Isaiah 56:6

This is the main indication that foreigners among Israel will also observe or at least “guard” the Sabbath (some Jewish sages draw a distinction between how Israel “keeps” and the nations “guard”), and the question then becomes, grasp what covenant tightly? Is this a reference to some of the “one law” sections of the Torah that laid out a limited requirement of observance of some of the mitzvot for resident aliens which includes Shabbat?

I won’t attempt to answer that now since I want to continue with a panoramic view of Isaiah in terms of the relationship between Israel and the nations (and since it requires a great deal more study and attention).

I’m reminded that in very ancient times, the “resident alien,” a Gentile who intended for his/her descendants in the third generation and beyond, to assimilate into Israel, losing all association with their non-Israelite ancestors, had a limited duty to obey just certain portions of the Torah mitzvot in the same way as a native Israelite.

The “one law” didn’t cover all of the mitzvot, but only a small subsection, such as a limited guarding of the Shabbat, which I mentioned above.

The “one law” didn’t cover all of the mitzvot, but only a small subsection, such as a limited guarding of the Shabbat, which I mentioned above.

Also, my understanding of the legal and scriptural mechanics behind the Acts 15 Jerusalem letter edict, is that the non-Jewish disciple of Rav Yeshua was to be considered, in some manner, a “resident alien” within the Jewish religious community of “the Way,” Jewish Yeshua-believers.

Putting all this together, we may infer some limited form of Torah observance for the non-Jew in Messiah, but beyond what we have before us so far, exactly what that entails may not be entirely clear.

Although the statement in Isaiah 56 saying that the foreigner was to “hold fast My covenant” seems general, there are only two specific areas mentioned: sabbath and prayer.

Regarding the Shabbat and Isaiah 56, I’ve written twice. The first mention is from My Personal Shabbos Project:

Of course, as I said before, I think there’s a certain amount of justification for non-Jews observing the Shabbat in some fashion based both on Genesis 2 in honoring God as Creator, and Isaiah 56 which predicts world-wide Shabbat observance in the Messianic Kingdom.

The second mention was from a companion blog post called Messianic Jewish Shabbat Observance and the Gentile where I mention using a particular Shabbat “siddur” that was specifically prepared for “Messianic Gentiles,” and this references Isaiah 56:7

This seems to bridge between the first specific item, Shabbat, and the second, which is prayer. I wrote of prayer and Isaiah 56 almost a year ago in this review of a sermon series:

Judaism makes a distinction between corporate and personal prayer, and man was meant to engage in both. Participation in the Jewish prayer services, at least in some small manner, is as if you have participated in the Temple services, which as Lancaster mentioned, is quite a privilege for a Messianic Gentile. It also summons the prophesy that God’s Temple will be a house of prayer for all nations (Isaiah 56:7, Matthew 21:13).

In addition to all of the above, we have this statement made by King Solomon as part of his dedication to the newly built Temple:

“Also concerning the foreigner who is not of Your people Israel, when he comes from a far country for Your name’s sake (for they will hear of Your great name and Your mighty hand, and of Your outstretched arm); when he comes and prays toward this house, hear in heaven Your dwelling place, and do according to all for which the foreigner calls to You, in order that all the peoples of the earth may know Your name, to fear You, as do Your people Israel, and that they may know that this house which I have built is called by Your name.”

–I Kings 8:41-43

This doesn’t seem to be limited to the resident alien temporarily or even permanently dwelling among Israel, but includes any non-Jewish visitor who, for the sake of God’s great Name, comes to Jerusalem and prays toward (facing) the Temple.

Of all the commandments incumbent upon both the Jew and the Gentile believer, it seems that prayer is to be shared among all peoples.

But what about Shabbat or, for that matter, any of the other commandments?

I want to limit myself (mostly) to Isaiah 56 since it seems to be a sticking spot for many non-Jews who believe it acts as a “smoking gun” pointing toward the universal application of all of the Torah commandments to everyone, effectively obliterating everything God promised about Jewish distinctiveness.

Since non-Jews are so prominently mentioned in this chapter, I decided to see what (non-Messianic) Jews thought of this.

The easiest (though highly limited) way to do so was to look up this portion of scripture online at Chabad.org see read Rashi’s commentary on the matter.

Here’s verse 3:

Now let not the foreigner who joined the Lord, say, “The Lord will surely separate me from His people,” and let not the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.”

Here’s Rashi’s commentary on the verse:

“The Lord will surely separate me from His people,”: Why should I become converted? Will not the Holy One, blessed be He, separate me from His people when He pays their reward.

My best guess at the meaning of this statement is that the Gentile should not convert to Judaism since, when Hashem gives Israel its reward, won’t the convert be set apart from His people?

But I’m almost certainly reading that statement wrong. It makes no sense to me, since converts, according to the Torah, are to be considered as identical to the native-born. I don’t have an answer for this one.

The other relevant verses are 6 through 8, and here’s Rashi’s only commentary on them:

for all peoples: Not only for Israel, but also for the proselytes.

I will yet gather: of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] of the nations) who will convert and join them.

together with his gathered ones: In addition to the gathered ones of Israel.

All the beasts of the field: All the proselytes of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] All the nations) come and draw near to Me, and you shall devour all the beasts in the forest, the mighty of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] the mighty of the nations) who hardened their heart and refrained from converting.

Referring to “foreigners” as proselytes or non-Jewish converts to Judaism is rather predictable and an easy way to avoid the thorny problem of Gentile observance of Shabbos or some other sort of association with Israel.

The last commentary seems to make some mention of “heathens,” possibly meaning that, in the end, Jews and non-Jews will turn to God, but ultimately, it seems, Rashi expects all non-Jews to convert to Judaism as their only means to become reconciled with Hashem.

My general knowledge of Jewish belief (and I suspect I’ll be corrected here) indicates that non-Jews will exist in Messianic days and those devoted to Hashem will be Noahides or God-fearers, just as we have those populations in synagogues today. They will have repented of their devotion to “foreign gods,” which from a more traditional Jewish perspective, will include (former) Christians.

So without further convincing proofs, I’m at an impasse. I can definitively state that part of a life of holiness for both a Jew and Gentile is prayer to the Most High God. Of course, that should be a no-brainer.

So without further convincing proofs, I’m at an impasse. I can definitively state that part of a life of holiness for both a Jew and Gentile is prayer to the Most High God. Of course, that should be a no-brainer.

The Shabbat is a bit more up in the air. While I can’t see any real objection to a non-Jew observing a Shabbat in some manner, there doesn’t seem to be a clear-cut commandment. In Messianic Days, Shabbat may well be observed in a more universal manner, though the exact praxis between Jews and Gentiles likely won’t be identical.

As the discussion in How Will We Live in the Bilateral Messianic Kingdom indicated, while the vast majority of the Earth’s Jewish population may reside in the nation of Israel in Messianic Days, there may be some ambassadors assigned to each of the nations, and thus, there may be an application of the Shabbat in the nations for their sake and for the sake of Jews traveling abroad for business or leisure reasons.

I also can’t rule out a wider application of Shabbat observance for the Gentile in acknowledgement of God as the Creator of the Universe, which we see in Genesis 2:3:

Then God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made.

That’s supposition on my part, but it’s not entirely out of the ballpark.

In any event, Isaiah 56 doesn’t give us as much detail about non-Jews in relation to the Torah as some folks might think. Pray? Yes. Pray toward the Temple in Jerusalem, even if you are outside Israel? Maybe. Couldn’t hurt.

Observe the Shabbat? Maybe in some fashion. I think this part will become more clear once Messiah returns as King, establishes himself on his throne in Jerusalem, and then illuminates the world.

Observe the Shabbat? Maybe in some fashion. I think this part will become more clear once Messiah returns as King, establishes himself on his throne in Jerusalem, and then illuminates the world.

In terms of what I’ve written before, prayer should already be part of a simple life of holiness, so Isaiah 56 doesn’t add to this. Some form of Shabbat observance is allowable but may not be absolutely required for the Gentile in the present age. Isaiah 56 doesn’t make it clear that a Gentile “guarding” or not “profaning” the Shabbat is also “observing” it, and even if we do observe, there’s still not an indication that such observance would be identical to current Jewish praxis.

Bottom line: when in doubt stick to the basics.

James,

RE: “The “one law” didn’t cover all of the mitzvot, but only a small subsection, such as a limited guarding of the Shabbat, which I mentioned above.”

That’s not true. And if you don’t believe me then here’s Rashi on the subject:

“49. one law. Not only with respect to the eating of the paschal lamb is the stranger equal to the native Israelite, but also in the duty to observe all other commandments [Rashi].” pg. 399 of Soncino Chumash (edited by A. Cohen).

Also, I don’t know if you’ve read my latest post, have you? Anyway, yirat, which is imprecisely translated as “fear” in passages such as the passage in 1 Kings you quoted, is really about seeing how awesome G-d’s commands are. Such a person who has yirat HaShem doesn’t think to himself, “Now let’s see…which are the commands I don’t really HAVE to do…” No, he says to himself, “I’m so exciting about G-d’s Torah! I want it all!”

Anyway, glad to see you still blogging.

Shalom,

Peter

Sorry, Peter — You simply can’t have it all, because you are not eligible to inherit in the land of Israel. If I understand your situation correctly, you are not a circumcised convert who is responsible for the entirety of Torah, nor are you a descendant of Yitzhak and Yakov/Israel to whom the inheritance of the Avrahamic covenant(s) apply, nor are you of the houses of Israel and Judah with whom the Jer.31 covenant is to be established. As I recall, you do not live in Israel, so it would seem that you do not even qualify to be living among the people of Israel as a “ger toshav”. Living among or near Jews in the galut doesn’t actually count, but we might stretch a point in your favor just to be accommodating, because we Jewish messianists do wish you to experience the grace that HaShem extends to you through Rav Yeshua’s teaching and ministry, and to welcome you to embrace the covenant principles voluntarily from where you are outside its boundaries (as in Is.56) even though you are not an obligated participant within its boundaries.

However, you’ve taken Rashi’s comments out of the context in which he placed them, just as you’ve previously taken out of context and overgeneralized passages where the Torah uses the phrase “one law”. But no one can say you’re not consistent, even if you consistently insist on pursuing the same error. With respect to the Passover, it is the *circumcised* stranger (i.e., the full convert) that may eat of it in full equality with Jews. And, nowadays, several centuries since Rashi offered his opinions, the modern practice, originating in galut conditions, of inviting uncircumcised non-Jews to participate in a seder, that does not actually include a sacrificed lamb but only symbolic reminders of it, has an underlying purpose of combatting the ancient blood libel against Jews. Non-Jewish symbolical participation is more effective than the older technique, still practiced, of opening the door to show the outside world the innocence of the proceedings. Non-Jewish familiarity with the symbols and the positive themes of Passover reduces the likelihood that these participants will join together with their neighbors to foment or conduct a pogrom against such unmistakably upright Jewish neighbors.

You are correct that “yirah”, as in “yirat HaShem” and “yirat ha-shamayim” is better translated as “awe” than what currently passes for “fear” in modern English usage. And, yes, the person who is in awe of HaShem doesn’t ask himself about how little he can get away with. On the other hand, he also doesn’t arrogantly claim too much for himself — particularly not aspects of HaShem’s covenant with the Jewish people that have never been assigned to him. He does not denigrate the grace to which HaShem has called him, nor disdain his position that is not under covenant, nor disdain the position of Jews who *are* under the covenant(s). The awe-filled gentile Rav-Yeshua disciple will seek to learn exactly what is most fitting to his relationship with HaShem, in all that he may do under the enlightenment of the kingdom-of-heaven mindset.

Peter, I’m sure you realize by now that we are going to disagree and that I have more in common with PL’s perspective on “one law” than yours. I can hardly believe Rashi would advocate Jews and Gentiles being mutually obligated to perform to the exact same mitzvot in the exact same manner.

Yes, I’m still blogging, thanks. Sometimes it helps to pause and reassess goals and motivations and I had a lot of encouragement to return to these “meditations.”

Proclaim Liberty,

There’s 2 things you have to do now to be taken seriously:

(1) Please support your false claim that I made the anti-Semitic assertion that I should have the Land of Israel. That is an outrageous and false claim. Alternatively, if you cannot support your ridiculous claim, you should apologize;

(2) Please support your claim that I took Rashi out of context. Please show how Rashi’s statement does not directly contradict James’ assertion that “one law” refers to a “small subsection” of the commandments. While you’re at it, perhaps you could show us how 2+2=5?

Shalom,

Peter

@Peter — Regarding Rashi out of context, you neglected that he was not addressing more than Passover, and that he was not intending to contradict the Torah’s requirement that participants who are allowed to eat the sacrificed Passover lamb are to be circumcised, which in modern terms is to be fully converted to Judaism. There is more to his context regarding references to the dangerous gentile Christian environment that forms a backdrop to many aspects of Jewish commentary in that era, but I’d need to look more closely at the passages you cited and their surrounding contextual passages to cite for you those which address your issue.

As for the other, I never accused you of an anti-Semitic claim about the land of Israel. I said that you aren’t eligible to inherit, which should demonstrate to you at least one of the differences between Jews and gentiles that is not subject to “one law” for both. Similarly, James addressed the issue that there is only a subset of Torah that can be applied to both, and that the “one law” notion is an unsupportable over-generalization.

Just a reminder, if we’re going to open this can of worms yet again, please remain civil and keep to the facts. Character assassination will not be tolerated and, as I’ve done in the past, I can close the conversation at whatever point I think it’s gone too far.

Thanks.

Signed, “The Management”

“The awe-filled gentile Rav-Yeshua disciple will seek to learn exactly what is most fitting to his relationship with HaShem,”

Mythos informed ancient governments with Divine Right and coronations, the religion/cult would take the myth and make it punctual in nature in a venue, the myth would inform the family on matters of birth, marriage, dowry and burial customs. These were all connecting points from the Big Story to daily life. The holy laws would mirror the will of the “gods.” Food. Attire. Art. Education. Linage. Sacred Land. Foundation story. All connecting points where the Big Story manifested itself in time. Being made in the Image, loving your neighbor, or having the Spirit does not really answer collective destiny absent revelation.

It’s hard for me as a gentile to actually see *tangible* connecting points between G-d and Gentiles corporately, because in the aforementioned list, there are none. Trouble is, faith life is punctual and tangible.

For the above reasons, I reckon that it is possible for Gentiles to have unique relationships with G-d on an individual basis, but it is impossible to have one on an ethnic/national basis without making up a myth of revelation or replacement to grant it some legitimacy. All national myth requires that. This is where Mormonism is actually kinda brilliant (made-up though it is): now Gentiles have a book that they are in, they have a holy law, they have a revelation, founder, family customs, a temple where G-d meets them, sacred diet, attire, art, education, a Messiah that came to them directly, rite of passage, lineage, sacred land, all the fix-ins of a robust religion revealed to them directly in their own story with G-d. Now if I could just believe it.

I guess Joseph Smith went and learned exactly “what is most fitting to his relationship with HaShem.” When the Direct Revelation (which is seen in religion as the font of legitimacy) outsources the unanswered social/ethnic questions to journeys of personal discovery, you get Mormonism, which begs to have found a font all its own. Fancy that.

I’m reading Brevard Childs on Biblical mythology in conjunction with Joseph Campbell, Ovid, and some Canaanite lore. One of the things I’ve come to understand is that where there is a mythic void – or when there exists a Story but it does not touch down anywhere in life – society abhors a vacuum. So people will fill it with something to staunch the sense of alienation. Results may vary. They’ll either rewrite themselves into the story (Mormons) or build their own connections to it they are to feel a stake in it (Supersessionism).

This is just a cold sociological observation. I still believe in the Tomb and the Dream like you, but remains is a point of severe frustration. It occupies my prayers and keeps me awake at night.

I take solace in the world of Jewish mystical texts like the Pesikta Hadta and others where Messiah comes and answers all questions. Perhaps there will be a world where G-d will say what Gentile life looks like.

Messiah now.

Sorry Peter.

I cannot fathom Rashi ever sharing a Pascal lamb with a gentile.

Drake,

So let’s talk about story. Jacob Neusner, the world’s leading scholar on Rabbinic Judaism (written 905 books, translated the entire Rabbinic corpus, etc, when I say “leading” I mean “leading”), he is famously a proponent of One Law. Here are some excerpts from 2 of his books (Recovering Judaism & The Emergence of Judaism) that show how Scripture and the Rabbis include Gentiles in the story of Israel:

RECOVERING JUDAISM:

The universality of Judaic monotheism emerges when we realize that that ‘Israel’ will encompass all who know the one true God. .. By Israel then is meant those who know God and accept his dominion, and by gentiles or non-Israel, those who worship idols. There are no other lines of differentiation in common humanity…Israel encompasses all those who worship the one God, and the rest are classified as idolaters…Those who possess the Torah–Israel–know God, and those who do not–the gentiles–reject him in favor of idols. To be Israel then means to know God, and to be gentile means not to know God. .. Israel then stands for humanity, fallen into death, risen into eternal life…Now ‘Israel’ within the same story encompasses all those who know the one and only God: the saving remnant of humanity in the aftermath of Adam and Eve, this time destined to life eternal.

THE EMERGENCE OF JUDAISM:

In the Torah and in prayers ‘Israel’ refers to the holy people of God: the children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob who stood at Sinai. ‘Israel’ refers to those who receive the Torah–God’s revealed will-and enter the covenant with God. ‘Israel’ then encompasses those born into the people and those that join the people by choice.

What difference does it make to be part of Israel? When people call themselves ‘Israel,’ they adopt for themselves and take personally the narrative of the Torah.

CONCLUSION:

Folks like PL and James like to make fun of One Law adherents. The reality is that our view is well-substantiated in Torah, in the Rabbinic Writings, and modern scholarship such as the work of Jacob Neusner (et al).

Shalom and Blessings,

Peter

Wasn’t the ger allowed to eat treife while a Jew was not?

@Peter: I can’t speak for PL, but I don’t experience myself making fun of you. I do experience myself disagreeing with you.

I haven’t read any of Neusner’s books, but in reading his Wikipedia page, a commentary on Neusner by Bible scholar James D. Tabor, and having taken a look at his book A Rabbi Talks with Jesus at Amazon.com, it certainly seems clear that he is not “Messianic” or otherwise a believer in or disciple of Rav Yeshua.

Therefore, I find it difficult to believe he has a perception of the Bible, God, and Yeshua that is in any way identical or even similar to yours (or mine for that matter).

I also noticed that he isn’t perfect or universally accepted. Again, according to links found at Wikipedia, his critics include Shaye J.D. Cohen, Craig A. Evans, Saul Lieberman, Hyam Maccoby, E.P. Sanders and several others. While I can acknowledge the body of knowledge Rabbi Neusner has contributed, you can’t hold him up as an undisputed expert.

It’s a shame that his personal website no longer exists. It might have provided a way to contact him directly and ask him point blank if he is a proponent of “one law” in the manner of say Tim Hegg. I suspect the Rabbi is not.

PL may be more familiar with Neusner’s works and perspective, but given the Rabbi’s background both as a Jew and as a scholar, I believe you may be reading what you want to read into certain paragraphs he’s written.

James,

Wikipedia is wrong. Let’s start with Shaye Cohen. Mr. Cohen tells his readers to go out and read Neusner’s writings (see “From the Maccabees to the Mishnah”). Craig Evans, he cites to the “significant evidence” found in the writings of Neusner (see Evan’s book “Jesus and the Ossuaries).

Hey, I could go through each one but you get the point. Your claim that these guys think Neusner is not an expert is totally bogus. They all go out of their way to claim he is a leading expert. In fact, they rely on Neusner’s scholarship when making their own assertions.

Peter

I didn’t say he wasn’t an expert, just that he’s not undisputed, no scholar is.

You also didn’t address the idea that Rabbi Neusner is not a devotee of Yeshua and most likely doesn’t conceptualize ‘one law’ in anywhere near the same way you do.

James,

Okay, so let’s define “One Law”. One Law means that the Torah is universal for those who know G-d and accept His dominion. Now let’s see if Neusner fits in that category:

“By Israel then is meant those who know God and accept his dominion, and by gentiles or non-Israel, those who worship idols. There are no other lines of differentiation in common humanity…Israel encompasses all those who worship the one God, and the rest are classified as idolaters…Those who possess the Torah–Israel–know God, and those who do not–the gentiles–reject him in favor of idols. To be Israel then means to know God, and to be gentile means not to know God.”

So he believes there’s 2 segments of humanity: those who fear G-d and keep the Torah and those Gentile idolaters who reject the Torah. Therefore, he is One Law. By the way, you don’t have to be a Believer in Yeshua to believe in One Law.

Peter said:

Let’s not and say we did. Remember, I’m writing these days to define my own praxis, not to define yours. You can do anything you want. And having discussed this topic about a billion times before, I don’t really need to rehash it. “Winning” is something Charlie Sheen is more interested in. I don’t have to “win”.

That said, I no more believe Rabbi Neusner would agree that you, as a Gentile, are obligated to refrain from driving on Shabbos, daven wearing a tallit gadol and tefillin, and keep separate meat and daily dishes in your kitchen than I believe Wallace and Gromit could find a good wensleydale on the surface of the Moon. I do believe that the Torah has universal applications, but those applications do not map to Jewish religious practice for the Goyim. You can choose to believe otherwise and live your life that way. I’m OK with that.

If you still need to read my other opinions on this topic, so a search on this blogspot for “one law” to find a representative list of my other arguments. I’m not writing blog posts just so I can cover old ground.

Steve,

Great question.

Deuteronomy 14:21, at first glance, appears to give the impression that a covenanted “ger” could partake of treif meat (nevelah). However, there are 2 types of gerim: paroikos (non-covenanted) and proselutos) (covenanted). In Deuteronomy 14:21 in the LXX, paroikos is used to translate “ger” because the LXX translators wished to make explicit that there are two types of “gerim”, the gerim who are covenanted (proselutos) and the gerim who are not covenanted (paroikos), and that the type of ger who was allowed to eat treif meat was in fact the “paroikos” (non-covenanted) ger. Conversely, we see in the One Law passages that “ger” is translated accordingly as a proselutos (covenanted) ger.

So how do we PROVE that there are 2 different types of ger? This is how:

Because Torah actually calls it iniquity for a ger to consume treif meat:

“And every soul that eateth that which died [of itself,] or that which was torn [with beasts, whether it be] one of your own country, or a stranger, he shall both wash his clothes, and bathe [himself] in water, and be unclean until the even: then shall he be clean. But if he wash [them] not, nor bathe his flesh; then he shall bear his iniquity,” (Leviticus 17:15-16)

Since Torah cannot contradict itself, we know there MUST be 2 different types of ger. And so the Sanhedrin which authored the LXX used 2 different terms to translate ger depending on the context. If it’s a covenanted ger then he’s a proselutos; if it’s a non-covenanted ger then he’s a paroikos (literally meaning he’s outside the house [of Israel]).

Hope that helped.

Shalom,

Peter

Hello James, from the land of Israel!

I read most of your post, and none of the comments, as I am getting ready to turn in for another day in the land.

I did want to share one thing with you – last Sabbath I spent the night at the Abraham Hostel. It is located in the Jewish area of Jerusalem. Everything is closed on Sabbath. So a Gentile (me) staying in that part of town, in a sense has no choice but to observe the Sabbath. If you want to eat, you must buy food ahead of time.

Now, I realize that I could go to other parts of town, but there was something beautiful about the peace and quiet of the day. Families walked together, congregations gathered,…it was beautiful. It reminded me of what Sundays were like, growing up as a kid in Queens, NY. Everything was closed on Sunday. It was a day to go to church and spend time with family. I remember all of us gathering in my Aunt Connie’s tiny eat-in kitchen for Sunday pasta.

And something I also experienced, being here during the holiday – many people greated me with ‘Chag Samaech’. I wasn’t wearing anything to indicate I might be Jewish. I had a backpack and fanny pack, so it was clear I was a tourist. But it was truly nice to be greeted in such a way.

We were on the Wall on Simchat Torah. I had blisters on my feet, so dancing was out of the question, but my friend was included in the women dancing with out question. It was a joyous occassion, and I was blessed to be included in it.

Hope all is well with you and yours!

I’ve been following your journey in Israel on your blog, Ro. You need to install a “like” button. I don’t always have something to comment about (I know that’s probably surprising), but I’d like to acknowledge that I read and enjoyed your blog posts.

You are a visiting Gentile in Israel, so as a matter of course, things are different for you there. There’s no reason for a Jew not to say Chag Sameach to a non-Jew during a festival. It’s all part of sharing the joy. And I agree there’s a peace in Shabbat observance, something the Church did instill in western civilization (albeit on Sunday rather than Shabbos) until the last generation or so. And if a non-Jew found herself in a synagogue on Simchat Torah, she might be invited to dance along with the Jews present, and celebrate the joy of Torah.

It’s not that I believe these things are strictly forbidden for us, just that we don’t have an iron clad set of obligations. If we are invited, it’s one thing, particularly in Israel. To make demands as some folks do on the other hand, is a completely different story.

I’m gratified that you’re enjoying your trip so much and I look forward to each of your detailed, informative, and very human blog posts describing what you are doing in Israel.

@Ro Pinto — So now that you’re in Jerusalem, should I expect to see you visiting my shul this Shabbat (Ro’eh Yisrael, corner of Narkis & Ussishkin)?

Here we go again on the “one Law” thing. A “ger” is a general term with sub-catagories such as Ger Nochri, Ger Toshav, and a convert Ger Tzadek. The mitzvot in the Torah that deal with signs of the bris between Israel and G-d are ONLY for yidden…period. Tzitzis, tefillin, Shabbos (on a grander scale) and the Chaggim, are only commanded to Jews. The moral and ethical aspects of the Torah are universal, everyone has an innate understanding that theft is wrong, murder is wrong, ect. Frankly I don’t need to wear tefillin or tzitzis for my faith to somehow seem valid or extra spiritual.

James,

RE: “Let’s not and say we did”

But you already did and that’s why I had to address it. You said “he doesn’t conceptualize one law in the way that you do.” You are basically asserting that he fits some other definitional category than One Law. “No, he can’t possibly be one law.” Well, why not? That’s exactly what he is. And that’s exactly what he said.

What a wacky conversation this has been. I show where Rashi explains One Law as applying to all the commandments. The response, “No, that cannot possibly be what he is saying.” I show where Neusner says all the Torah applies to the segment of humanity that follows G-d. The response, “No, that cannot possibly be what he is saying.”

It’s like I’m showing the equation 2+2=4 and people keep scratching it out and saying. “No, that’s not right. You did it wrong.”

@Peter — Neither the Torah nor the much later rabbinic writings are so simplistic that you could adequately compare them with a simple arithmetic equation such as 2+2=4. Part of the disagreement directed against your assertions is precisely because you mistakenly treat them thus and ignore the bigger, more complex, picture.

OBTW, Peter — I agree with James that neither of us is “making fun of you”, which is to say we are not ridiculing you. We are both, each in our own manner, telling you that a particular notion that you purvey is in error. It is never “fun” to do that to someone such as yourself, who clearly has invested significant mental and emotional energy to pursue a particular path of dedication to HaShem. It is not impossible that whatever motivation is truly driving you in the direction of full Torah observance may be rooted in the limited set of justifications that do exist for a gentile disciple of Rav Yeshua to become fully converted to Judaism. That is not, however, justification to seek such appropriation of Torah, Jewish praxis, and covenantal responsibility for everyone.

While certainly I acknowledge the massive volume of scholarship product developed by Jacob Neusner, he apparently supported, in your citation, a common black-and-white version of the universe that does not allow for gentiles to exist as gentiles who have repudiated idolatry and turned to HaShem without converting to Judaism. Such perspectives existed also in the first century, as evidenced by the Acts-15 discussion in the apostolic writings. Such a perspective fails to recognize the nuances that Isaiah brought out in chapter 56 regarding “foreigners” (“b’nai nechar”) who cling to HaShem’s covenant in a manner that is described as subtly different from the Jewish responsibility to perform its precepts. For example, his characterization of how these foreigners guard the Shabbat is to keep from profaning it (i.e., not treating is as a common ordinary day). That differs from the instructions about how Jews are to sanctify the Sabbath with a holy convocation and a set order of arrangements and offerings in the sanctuary and avoidance of “melakhah” activity and a host of other details. Nonetheless, their sacrifices are to be accepted on HaShem’s altar, such that His house should be a house of prayer for all peoples (not only for Jews). Indeed, in verse 3 an interesting verb is used to characterize the individual foreigner who has “joined himself to HaShem”. He is described as “nilvah”, which is explicitly one who “accompanies” another. It is used in modern terms in Israel for an adult driver who must accompany a newly-licensed driver for a trial period. In more ancient terms (still in modern use) it describes those who accompany the body of a deceased to the grave-site. This characterization of accompaniment fits very well with the notion that James has often cited for gentile disciples operating “alongside” Jewish ones.

Tony,

RE: “The moral and ethical aspects of the Torah are universal, everyone has an innate understanding that theft is wrong, murder is wrong, ect.”

G-d’s moral value is that homosexual marriage is evil, most countries DENY this value; G-d’s moral value says murder is wrong, most countries say it’s okay to murder unborn babies.

Here’s the problem: Your assertion is that the Torah has provisions which are not moral (i.e. do not reflect G-d’s values). Pray tell, which ones are those?

The reality: the Torah is the perfect expression of G-d’s moral value system. The Torah is morality. I dare you to show us which mitzvot are not moral (i.e. do not reflect the values of HaShem).

Shalom,

Peter

Peter,

Just convert.

“No! Anything but that!” ***GASP!***

Every fear hides a wish, bud.

@Tony: Well said. Thanks.

@Peter: I wrote this morning’s meditation with you in mind. Have a look. We don’t have to agree and, in my opinion, we don’t all have to conceptualize our relationship to God in the same way. Relax. My personal viewpoint of my relationship with God affects you not at all…unless you let it.

@Drake: LOL (Sorry Peter, but it was funny).

Drake,

Conversion happens in the heart not via ritual.

However, adoption into a specific tribe (i.e. the Jewish tribe) happens with a ritual. But I’m not looking for a tribal affiliation with the People of Israel. G-d has already joined me to His People without the necessity of tribal adoption because he converted my heart. I’m a non-tribally-affiliated member of Israel. No land rights, don’t need any. I’d be happy to live in Israel one day as a servant. That’s my heart: I want to serve Israel and bless Jews.

It excites me just to think of it! Baruch HaShem!

Shalom,

Peter

Israel was allotted tribal land in Joshua. I would imagine that if you did just so happen to trip on a razor, eventually a place would be allotted to you by another Yehoshua of sorts at the top of days. You’r either a Levite or you have land. It’s part of the responsibility.

“I’d be happy to live in Israel one day as a servant. That’s my heart: I want to serve Israel and bless Jews.”

And how better to as one of them? But you could also do that as a gentile. Soldiers who deploy long enough in a land tend to “go native.” Think Dune, Avatar, and Farewell to the King. Such a lovely metamorphosis might have happened to Cornelius’ family had they lived there undisturbed.

Imagine you got this girlfriend named Judith. I always imagine my personification of Judaism looking like a punkarella or Sarah Silverman, a winsome street runaway who works at a vinyl record joint in a college town where she watches every new wave come and go. She dresses in black, studs, and tragic makeup, but proves to be one of those ride-or-die-to-the-end gems that leaves you wondering where your angel in black picked it up her blend of streetwise and old-timey.

Anyway: You’ve been shacking up with her for some time. One day Judith comes to you, puts down her cassette player, and says while popping her gum: “honey. I’m pregnant.”

You, like me, have kind-of done just that in your own way, and we’ll have some decisions to make in the long-term. You entrusted your neshamah to this gal, and she’s been growing it and shaping it, and now she reasonably expects you to stand and deliver. She’s skittish from commitment herself, having run away from home years back. But now she really sees the draw. Her father sure as hell won’t accept you for her long string of losers before you stepped into the picture. But you know what? What you have might be real, and if the kid you broken lovebirds make looks uncannily like Peter, then maybe it was written from the start. So take a chance on Lil’ Miss Ride-or-Die. Get hitched, have the kid, and ditch the two-star town.

Just don’t make her wait too long. Rabbis may use a scalpel, but Judith uses a sword.

Think about it.

I gotta get some coffee.

*drops mic*

Peter,

PL wrote:

“It is not impossible that whatever motivation is truly driving you in the direction of full Torah observance may be rooted in the limited set of justifications that do exist for a gentile disciple of Rav Yeshua to become fully converted to Judaism.”

Being Pro-Life, I believe conversion should be safe, legal, and rare. So in all seriousness, PL raises an interesting and warmly diplomatic point for a guy who normally stiff-arms gentile observance (sorry PL). You keep coming up with all sorts of twisted formulations of “Israelite without a specific tribe” which is eschatologically impossible. Or Israelite but not Jew, etc. In the tangle of all these frustrations, at the root you seem to exude quite a bit of zeal and emotional investment in the Dream. And yet you take anything but the most obvious course of action just offered to you.

If you feel the aborning emotion of kinship with a people, to serve them and live among them, perhaps PL has a point.

Maybe your destiny is as a gentile. Maybe it’s as a convert. Maybe we’ll get to Gan Eden and Avraham will correct us all and admonish us for not heeding you (I don’t think so, but hey). But I don’t think the NT’s takeaway should be that conversion is the enemy of faith, that you should see it as a bogie, but instead that the wrong motivators for converting are. If that’s true, at least think about it. You might be very happy in such a life. As not just some lost Israelite, but a Jew who chose.

On a blog of mostly rampant dissatisfaction, I wish you every happiness.

Good shabbat amigo.

@James. I’ve tried to find an add on for wordpress, though not diligently. Week look again when i get back to the US. Thank you for following!

@PL – I so enjoyed meeting you today. Maria and I truly enjoyed worshiping with you and your kehilot. Hoping to see you next week. Shavua Tov!

@Ro — I’m glad you enjoyed the service and found it educational (as you mentioned to me in person). On an educational note, I should also mention that “kehilot” is the plural form; a single congregation is a “kehilah”. May your travels in the Land be safe; and I hope likewise to see you again next Shabbat.

@Peter — I’d like to pick up a thread of yours, which equated the notion of “moral” with that of “reflecting HaShem’s values”, in order to point out that those notions are not quite equivalent. “Moral” is actually related linguistically to “mores”, which are folkways or prescribed practices — hence, “moral” is certainly intended to indicate right actions and right thinking — however, there are Torah commandments about practices which are incumbent upon Cohanim, but which Levites would be forbidden to perform. These commandments and practices unquestionably reflect HaShem’s values, but they are “moral” for one group but not for another. Similar distinctions exist between Levites and ordinary Israelites; and distinct commands exist for lepers, for women, for “strangers”, for different kinds of “ger”, for “nazirites”, and for people under special conditions of impurity. It is not “immoral” to contract impurity — though one may contract impurity through certain immoral behaviors — and under some conditions one is required to do so to fulfill certain family obligations. Thus we can see that, though all of Torah demonstrates for us the effects of HaShem’s values, some of its prescribed actions are conditional and not at all universal. However, the common usage and conception of the English word “moral” has to do with universally proper behaviors that are actually only a subset of Torah’s prescribed behaviors. This is why it became popular more than a century ago to describe some commandments as “ceremonial” rather than “moral”. While I find this division also to be somewhat inaccurate, it does illustrate that others also have recognized that there is more than merely morality in Torah.

PL,

Differentiating between common Israelites and the Levites and Kohanim DOES reflect a value of HaShem. Thus, if “moral” means G-d’s value, then it would certainly be immoral for a Levite or Kohen to violate the laws that G-d gave to them. And, conversely, it would be immoral for a common Israelite to act like a Levite or Kohen.

You can’t get around the rather obvious fact that each mitzvah conveys a “moral” value, a G-d-value.

And this silly distinction of moral and non-moral commandments goes back a lot farther than 100 years. It actually started with Thomas Acquinas:

“We must therefore distinguish three kinds of precept in the Old Law; viz. ‘moral’ precepts, which are dictated by the natural law; ‘ceremonial’ precepts, which are determinations of the Divine worship; and ‘judicial’ precepts, which are determinations of the justice to be maintained among men,” (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 2a, Question 99, Article 4)

CONCLUSION:

You can’t tell Gentiles to just keep the “moral” commands in Scripture. It doesn’t work that way. They’re ALL moral.

Shalom,

Peter

@Ro and PL: Glad the two of you were able to worship together last Shabbat in Jerusalem.

@Peter re PL’s commentary: Are all Torah commandments “moral?” Kind of depends on how you define “moral”. You’re implying that it’s “immoral” for a non-Jewish Christian to not wear tzitzit or daven wearing tefillin because the commandments are in the Torah.

However (and I know this has been said many times before), certain commandments are aimed at certain populations. They aren’t all universal. An ordinary Israelite is permitted to marry a widow but not so the High Priest. The ordinary Israelite marrying a widow is not committed an “immoral” act but the High Priest is, that is if you believe of the mitzvot define “morality.”

What about the commandments that don’t seem to have a logical purpose and are only obeyed because Hashem said to obey them. Are they “moral?”

I tend not to get hung up in this whole mess and prefer to view the Torah commandments relative to how or if they apply to certain populations. Well over half of the 613 commandments can’t be observed by Jews today, especially outside of Israel, largely because there is no Temple, no working priesthood, and no Sanhedrin.

As I’ve also said before Peter, you can choose to take on board whatever commandments you desire, but that’s a decision you are making for yourself. You can’t make it for anyone else.

Each of us negotiates his/her relationship with God. I am not your intermediary and you are not mine. God will judge us in all due time. I suspect He won’t send me to Hell for all eternity without an electric fan or a bucket of ice water simply because I don’t believe I’m commanded to wear a tallit katan under my clothing.

I’ve got my hands full day-by-day attempting to live a simple life of holiness.

I just came across an article about the universality behind the principles regarding the Shabbat. It’s not so much that it is moral to observe or guard Shabbat in some fashion and immoral if you don’t, but a matter of what is good for us.

If Hashem created the Shabbat to be of benefit, not only to Israel, but all of humanity, then it’s in our best interest to have a day of rest once a week, and to our detriment if we choose not to. That way, we may say that a person who chooses not to have a day of rest in some manner isn’t being immoral, they have just chosen to make their life just a little bit harder.

James,

In your post entitled “A Simple Life of Holiness” you wrote:

“Having a relationship with God, for anyone, is a matter of allowing your day-to-day life to reflect righteousness and holiness. How? It’s not that complicated. Do good things to other people.”

That’s sounds great…until you stop for one moment to define the terms you’re throwing around. What is good? What is moral?

But instead of trying to find out what is good in the objective sense, you’ve reduced it to a subjective and self-centered question: “what do I think is good?”

But it’s not about what YOU think is good. It’s about what G-d thinks is good. Morality, as a concept, is meaningless if it can mean whatever WE think is good (subjective standard). But it is meaningFUL if it refers to whatever G-D thinks is good (objective standard).

That’s why you have to define morality as “G-d’s value system” which then means you can’t just make up on your own a simple life of self-defined “holiness”. Once you take a moment to define morality objectively then 2 things must follow:

(1) You’re forced to use Scripture to find G-d’s value system (i.e. you’re forced to employ the ONLY objective value system we have received);

(2) You’re forced to accept that ALL of the Torah is infused with G-d’s values and that is therefore not law as opposed to morality but law which IS morality.

Next, I’d like to address your comment:

“You’re implying that it’s “immoral” for a non-Jewish Christian to not wear tzitzit or daven wearing tefillin because the commandments are in the Torah.”

If I believe that there’s no such thing as morality apart from the Torah then I wouldn’t say that Christians are immoral, I would simply say that they have fallen short His legal standard just as we all have fallen short and all must rely on G-d’s patience and grace.

I also said:

I think at our core, any of us who have attempted to live a life as a believer in Yeshua have a basic idea of what is sin and what isn’t. I don’t need to attempt to keep the portion of the 613 commandments in the Torah that are still possible for a Jew to keep as a Jew in order to know what is good and what is evil.

You witness someone leaving an ATM machine who has forgotten to remove his card. Do you use the card to withdraw more money from his account, or do you call to him and return his card?

That’s just one example of evil vs. good and I bet you didn’t have to study the Torah to know which is which.

I don’t have to live life like a Jew in order to understand what is good and then to do good (or to struggle with my evil inclination to overcome it so I will then do good).

James,

Conscience is great for some things–like avoiding harm to others. But it’s not always helpful (and often downright harmful) when it comes to identifying what is good in G-d’s eyes.

Does conscience tell you that it’s wrong to eat a bloody steak? On the contrary, it seems natural for a man with cuspids (a.k.a. Canine teeth) with their sharp points for tearing flesh, it seems natural to eat steak with the blood. Conscience doesn’t tell us that it’s wrong to do this. We FEEL no qualms whatsoever. On the contrary, we feel great when we do this thing…a thing that G-d happens to hate.

How about if a guy has 2 homosexual friends and they’re getting married and they say “Please come to our wedding!”? Conscience will naturally lie to the guy and say “It’s okay to attend the wedding. Let love win!” And most people these days want to do something “good” for their friends and their conscience says “If you don’t go, you’ll be hurting this couple!”

Conscience is not always helpful. You cannot rely on it to live the “simple life of holiness.” You MUST have an objective standard. And we have only ONE candidate for the objective standard: the revealed Will of G-d in Scripture. And it ALL of the commandments in Scripture are moral (i.e. reflect the values of G-d).

@James — A few posts back, Peter wrote:

“Differentiating between common Israelites and the Levites and Kohanim DOES reflect a value of HaShem. Thus, if “moral” means G-d’s value, then it would certainly be immoral for a Levite or Kohen to violate the laws that G-d gave to them. And, conversely, it would be immoral for a common Israelite to act like a Levite or Kohen.”

And in his latest post, he advocated for an objective standard to guide or correct natural lapses of the conscience. Of course, Torah, and the scriptures in general, provide such a standard. Moreover, Peter’s logic above was impeccable regarding HaShem valuing the distinction between Cohanic priests, Levites, and common Israelites. Since it would be immoral for a common Israelite to act like a Levite or Cohen, it is likewise immoral for a non-Jew to act like a “common Israelite” (i.e., a Torah-observant Jew).

Hence (or, if one prefers, “ipso facto”) the only subset of Torah that non-Jews may enact morally is that subset which applies to all humanity — even to the metaphorical children of the faith-filled, pre-circumcised, pre-covenantal, Avraham the “friend of HaShem” who will bless themselves by the seed of Avraham (that is, by both singular and plural meanings of the word “seed”).

Now, we might muse about the Torah’s example in the provision of the Nazirite vow, and its stringent provisions by which an ordinary Israelite could temporarily pursue a special kedushah that would ultimately enable him to present a sacrifice in the manner of a Cohen. Might there be some analog to this for a non-Jew, to enable his temporary participation in the activities of a “common Israelite”? Can we identify any actual need for such an analog? We know that non-Jews were able to offer sacrifice via the Levitical priests, similarly to the offerings of common Israelites, so apparently no special kedushah was required for that (though a cleansing mikvah was likely a pre-requisite). Certainly a non-Jew might convert to become like a common Israelite; but that would be a permanent change rather than a temporary one comparable to the Nazirite vow. Apparently the cleansing by immersion in water and HaShem’s spirit was deemed by the Apostolic Council sufficient for non-Jewish disciples of Rav Yeshua to enable them to enter fellowship with Jewish disciples, though that did not require of them more Torah observance than the Acts-15 basics — and Rav Shaul actively discouraged conversion. Non-Jewish disciples are certainly able to exploit the symbolic sacrifice proved in Rav Yeshua’s martyrdom, to obtain existential atonement; and there is no scriptural expectation that such disciples should further emulate Jewish ones beyond the moral realms of kindness, charity, sexual purity, and general uprightness of character — for which the Torah and the apostolic writings do offer general instruction — hence there would seem to exist no need at all for a non-Jewish Nazirite analog, nor a moral means for a non-Jewish disciple to take upon himself more than that subset of Torah principles cited above as applicable to all humanity.

PL,

RE: “Since it would be immoral for a common Israelite to act like a Levite or Cohen, it is likewise immoral for a non-Jew to act like a “common Israelite” (i.e., a Torah-observant Jew).”

Only if Scripture calls for non-Jews to remain distinct from Israel would it be immoral for a non-Jew to act like a common Israelite. But what does Scripture say?

We read that all nations will go up to learn the Torah, that all flesh will worship on Shabbat, keep Sukkot, that keeping Torah is the “whole duty of man”, that it is “instruction for mankind”, that the Tree of Life (i.e. the Torah) the way to which was blocked in Genesis 3:24 will once again be available to all mankind that believes in Yeshua:

“Blessed are those who wash their robes, that they may have the right to the tree of life and may go through the gates into the city. Outside are the dogs, those who practice magic arts, the sexually immoral, the murderers, the idolaters and everyone who loves and practices falsehood,” Revelation 22:14,15

That’s as crystal clear as it gets.

Shalom,

Peter

@Peter — Do you think we have come anywhere near to the conditions of Is.66:23? Or Zech.14? Do you think present conditions support some degree of attempting to behave that way? Scripture does most certainly tell Jews to remain distinct. Tenakh tells non-Jews virtually nothing directly, because it was not addressed to them. The apostolic writings note the continuing validity of Torah and Prophets (i.e., the Tenakh), the distinction between Jewish responsibility for Torah observance and the lack of legal obligation to it for non-Jewish disciples, and discourage non-Jews from converting to Judaism lest they become thus responsible for full Torah observance. There is a significant difference between the expected procedures for worship as conducted by Jews and by non-Jews, which may be expected to continue even under future conditions (“from one Rosh Hodesh to another and one Sabbath to another”) envisioned by the prophets. All the distinctions we’ve discussed in previous posts will still be valid throughout the messianic era. Access to the Tree of Life doesn’t eliminate those distinctions. Repudiation of sexual immorality, idolatry, magic, falsehood, etc., and “washing one’s robes”, doesn’t do that either. Clean-robed gentiles will (and already do) have access, alongside Jews, to HaShem, to atonement, and to other spiritual blessings; but that does not mean that they will perform identically the same tasks or cultural activities, religiously or otherwise; nor should they ever expect to do so.

Thus, of course it is immoral, against HaShem’s values and expressed wishes, for non-Jews to seek to behave as if they were Jews under the full responsibility of the Torah covenant rather than as the non-Jews they were created to be. They must glory in their position of having been cleansed by His freely-offered grace and lovingkindness — made into righteous members of the non-Jewish families of the earth — so that HaShem may be acknowledged as King over all nations and not merely over the Jewish one that has been His first priority and chosen instrument for the redemption of all humanity.

@PL: While it’s interesting to consider some sort of analog to a Nazarite vow for non-Jews, off the top of my head, I can’t think of any Biblical precedent for it. I’ll have to stand by my original statement that we non-Jews have our hands full with the subset of Torah commandments that apply to us, those that are universal and are not specifically identified with the Jewish people and Israel.

@Peter: Since I don’t believe that we non-Jewish disciples of our Rav literally become Israel when we come to faith, those laws that specifically apply only to Israel don’t apply to us, that is, me and thee.

Of course you know that already, so the best we can hope for is to talk in circles.

@James — Well of course there’s no biblical precedent for it. That’s exactly why I described the notion as something to muse about, much as ‘Hazal did with innumerable Torah passages. My conclusion was, as you saw, that there is no identifiable need for it (as well as no precedent) because there are already provisions in place for various appropriate levels of kedushah, hitkarevut, dvekut, and the like for non-Jewish disciples, and even conversion where a permanent change is deemed appropriate. Hence Peter ought to be able to approach HaShem however closely he feels he needs to do, within the frameworks and methods that you have outlined.

Agreed. I think non-Jews in Messianic Jewish or Hebrew Roots space would be a lot happier if they (we) just pursued who they (we) are supposed to be rather than going after someone else’s identity.

PL & James,

You know…I’m not the first person to notice that the commandments in Torah are so beautiful and wise that they should be observed by universal mankind. We read in the writings of Philo that the reason that the Septuagint was created was so that the rest of the world could employ the commandments and thereby “correct” their ways:

“(36) [The men selected to translate the Torah into Greek] judged [the island of Pharos] to be the most [pure and most peaceful location for preparing the translation]…and there they remained, and having taken the sacred Scriptures, they lifted up them and their hands also to heaven, entreating of God that they might not fail in their object. And He assented to their prayers, that the greater part, or indeed the universal race of mankind might be benefited, by using these philosophical and entirely beautiful commandments for the correction of their lives,” Philo, Moses 2.36

And this idea that the Torah is something that all the world should want–this idea is put forth time and time again in Scripture. Yet you both would have us believe that such a viewpoint never existed and that for universal humankind to pursue the commandments is “immoral”–an attempt to rob someone else’s identity.

I’m confident that the readers of this thread will see that the evidence for the universality of Torah is overwhelming. We can leave it at that.

Shalom,

Peter

I’ve already written about the universality of Torah and non-Jews studying Torah. It’s just that my idea (actually, the Jewish idea) of how the Torah is “universal” differs from yours.

On a related note, having renewed my interest in writing short bits of fiction, I took sort of a challenge and decided to “finish” the Book of Jonah. It’s been noted more than once, that the book seems to be unfinished. In my opinion, it ends on a cliffhanger: how is Jonah going to respond to Hashem’s challenging question about Nineveh. I decided to add a fictional fifth chapter to Jonah. The interesting result, at least for me, is how it seems to re-enforce God’s care and concern for all people and nations. However, I doubt that Jonah taught the people of Nineveh to don tzitzit and lay tefillin anymore than the Apostle Paul taught his non-Jewish students to do so.

I think that, just as in ancient times, we non-Jews can certainly learn from the Torah and from Jewish teachers, but that doesn’t make us Jewish nor does that require us to “behave Jewish” in order to draw nearer to God. The first step is repentance and if we are wise, we take that first step every day.

Keep up the great work here, brother James. I don’t get to read all the posts but the ones I have read are often encouraging.