The best evidence that the temple was the locus of prayer during the First and Second Temple periods is the book of Psalms. Virtually all the biblical psalms, even those that lament personal or national catastrophes or that hail a king at this coronation, are hymns of praise to God. They range in date from the period of the monarchy, if not earlier (some of them are Israelite versions of Canaanite or Egyptian hymns), to that of the Maccabees.

The best evidence that the temple was the locus of prayer during the First and Second Temple periods is the book of Psalms. Virtually all the biblical psalms, even those that lament personal or national catastrophes or that hail a king at this coronation, are hymns of praise to God. They range in date from the period of the monarchy, if not earlier (some of them are Israelite versions of Canaanite or Egyptian hymns), to that of the Maccabees.

All these texts imply that the recitation of prayers was a prominent feature of Jewish piety, not just for sectarians like the Jews of Qumran but also for plain folk. Jews who lived in or near Jerusalem prayed regularly at the temple. This is the plausible claim of Luke 1:10, “Now at the time of the incense offering, the whole assembly of the people was praying outside [the temple],” and Acts 3:1, “One day Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer, at three o’clock in the afternoon.”

By the third century BCE, diaspora Jews began to build special proseuchai, which literally means “prayers” but probably should be translated “prayer-houses.” Instead of “prayer-houses,” the Jews of the land of Israel had synagogai, which literally means “gatherings” but probably should be translated “meeting-houses.” Whether they prayed regularly in their “meeting-houses,” which are not attested before the first century CE, is not entirely clear.

The history of this (Amidah or Eighteen Benedictions) prayer is immensely complicated, but its basic contours were established no later than the second century CE, and its nucleus certainly derives from the latter part of the Second Temple times. It bears obvious similarities to the Lord’s Prayer (Matt. 6:9-13 and Luke 11:2-4).

…by the end of the Second Temple period, sections of the Torah were read publicly in synagogues every week.

The purpose of all these rituals was, as the Torah repeatedly says, to make Israel a “holy” people (Exod. 19:6; Lev. 19:2; Deut. 7:6). To better achieve this objective, the Jews of the Second Temple period developed new rituals, broadened the application of many of the laws of the Torah, and in general intensified the life of service to God.

After the destruction of the temple, the petition was changed from a prayer for acceptability of the sacrifices to a prayer for their restoration, and the petition entered the Eighteen Benedictions. In rabbinic times, the prayer was still in flux.

This practice is based on the idea that God can be worshiped through the study of his revealed word.

-Shaye J.D. Cohen

Chapter 3: The Jewish “Religion:” Practices and Beliefs

From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, 2nd Ed.

Forgive the rather lengthy history lesson from different portions of this chapter in Cohen’s landmark book, but as I’ve continued to read from his work, I’ve been struck by how Judaism developed significantly in practice and in its comprehension of a life of devotion to God from the days of the Mishkan (Tabernacle) in the desert to the post-Second Temple era. Some time ago, I began a series of blog posts intended to outline the evolution of Judaism as it applies to Yeshua (Jesus), halakhah, and the “acceptability” of the various Judaisms in any given age and across time to the God who established Israel as a nation. You can follow the link at the end of Part 1 of the series to review all of my comments to date, which ends at Part 5. I had intended for Messiah in the Jewish Writings, Part 1 to be the “sixth” part of the series, but it was pointed out to me that certain “weaknesses” in the scholarship of the material from which I was quoting made it unsuitable for that purpose.

Before proceeding, you should probably review Noel S. Rabbinowitz’s paper “Matthew 23:2-4: Does Jesus Recognize the Authority of the Pharisees and Does He Endorse their Halakhah?” which can be found as a PDF as published in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 46:3 (September 2003): 423-47. That, along with reading the other “Evolution” blog posts in this series, should provide the foundation for continuing (and ultimately concluding) the discussion here.

In providing the series of quotes from Cohen’s book, I intended to illustrate how what was acceptable Jewish practice in worship, Temple sacrifice, and prayer developed over time and was never a single, static set of religious rules and procedures that perfectly reflected the intent of the Torah and God in the life of Israel. Sometimes in certain corners of Christianity and its variants, we find people who sincerely are seeking a more authentic method of practicing their faith, based on some sort of idealized and perfect template or model that was established, either by Moses or Jesus. Somehow that particular set of behaviors is believed to be what God wants us to do and is the only valid model by which we should construct our faith practices in the present age.

But as the title of this series implies, perhaps the human practice of worshiping God can never be static nor was it ever intended to be a single set of rigid rules and concrete regulations that never modified in the slightest across the long centuries between Sinai and the present.

I don’t mean that right and wrong don’t have timeless value and that God changes His requirements for humanity at a whim, but humanity changes, circumstances change, and what seems right to do at one point in human history seems very much different at another point on the timeline of existence. Surely how Solomon viewed what was proper worship differed greatly from what the Rambam might have considered right Jewish practice, and yet can we say that either one of them (or both) was wrong? They were both certainly convinced that they were doing what God required, but who they were, where they lived, and the demands of history upon both of these men (and the untold scores that lived before and since) were radically dissimilar.

But while you may understand this relative to the history of the Jewish people, what at all does this have to do with believers in Jesus and who we are in Christ?

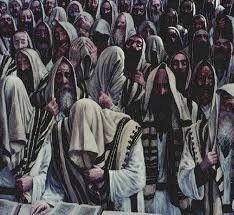

Agrippa’s first full year as king over Judea (41/42 CE) was a Sabbatical year. Drought had already begun to hamper the land. The people were gathered for Sukkot to pray for rain and to hear the new king read from the Torah (see Deut. 31:10-11). The apostles and the disciples of Yeshua were present along with the rest of the pious of Israel to witness the historic event. Their hearts burned within them, jealous for the Master. They longed for the day when King Messiah will stand in the Temple and read the Torah aloud to the assembly of Israel.

-D. Thomas Lancaster

Torah Club, Volume 6: Chronicles of the Apostles

from First Fruits of Zion (FFOZ)

Torah Portion Shemot (“Names”) (pg 329)

Commentary on Acts 12:1-24

Lancaster is no doubt taking a bit of poetic license in describing whether or not the hearts of the apostles were “burning” on this occasion, but it does cast the early Jewish disciples of “the Way” in a light that integrates them with overall Jewish religious and social participation. In the church, we tend to think of the “early Christians” as a body wholly apart from the various Judaisms that surrounded them, but as I’ve mentioned before, the Jews who were devoted to the Messiah as part of “the Way,” were just as much a valid sect of Judaism as any of the other Judaisms (Pharisees, Essenes, and so on) with which they co-existed.

Lancaster is no doubt taking a bit of poetic license in describing whether or not the hearts of the apostles were “burning” on this occasion, but it does cast the early Jewish disciples of “the Way” in a light that integrates them with overall Jewish religious and social participation. In the church, we tend to think of the “early Christians” as a body wholly apart from the various Judaisms that surrounded them, but as I’ve mentioned before, the Jews who were devoted to the Messiah as part of “the Way,” were just as much a valid sect of Judaism as any of the other Judaisms (Pharisees, Essenes, and so on) with which they co-existed.

In fact, the Jewish disciples of the Master in the days recorded by Luke in the book of Acts can only be separated from overall, normative Judaism anachronistically.

The King James Version of Acts 12:4 translates the Greek “pascha” as “Easter.”

The Greek word “pascha” (which transliterates the Hebrew “pesach”) occurs 27 times in the New Testament. In every instance except Acts 12:4, the King James translators rendered it as “Passover.” In Acts 12:4, they retained William Tynsdale’s anachronistic, Christian rendering and translated it as “Easter.”

The translation betrays a theological bias. It assumes Christianity replaced Judaism. Christ cancelled the Torah, and the Christian Jews would not have been keeping Passover any longer. In reality, the apostles had never heard of a festival called Easter. They had no special Christian festivals. They kept the Passover along with all Israel in remembrance of the Master, just as He had instructed them… (Luke 22:19)

-Lancaster, pg 338

Lancaster continues in his commentary, explaining that the separate Christian observance of Easter wouldn’t be established until the Second Century CE as the Gentile believers in Rome began to neglect observing Passover, but began to revere the Sunday that fell during the week of Unleavened bread as the day of Christ’s resurrection. As you can see, the passage of time and the demands of history have resulted in both Judaism and Christianity evolving and changing how they practice their divergent methods of worshiping God. In fact, the divergence of “the Way” from the rest of the Judaisms post-Second Temple is likely part of those historical requirements.

Is all this desirable? Probably not. That is, it would be great to have a Christianity that actually remained a normative part of Judaism and was able to include Gentile practitioners who came to faith in the Messiah, but such was not to be.

Lest you be wise in your own sight, I do not want you to be unaware of this mystery, brothers: a partial hardening has come upon Israel, until the fullness of the Gentiles has come in.

–Romans 11:25 (ESV)

Paul seems to be telling us that the schism between the Gentile and Jewish believers was inevitable for the sake of the Gentiles and that, referencing Isaiah 59 and Jeremiah 31, by doing so, all Israel will be saved. (see Romans 11:26-27)

If Judaism was practiced differently and in fact, in radically different ways between the ancient times of Moses, David, and Solomon, the time of the Babylonian exile, the time of Herod, the Second Temple, and the rise of “the Way,” and in the post-Second Temple rabbinic period, can we say that all of these Judaisms are “valid?” I don’t think we have much of a choice but to say that they are. If you disagree, then you have to point to some place in history and say “here’s where the Jews made their big mistake.” I know that many Christians will point to Jesus and say that the Jewish rejection of their own Messiah caused them to become lost and gave rise to the “age of the Gentiles,” but be careful. For the first fifteen years post-ascension, only Jews were disciples of Jesus Christ. Even after Peter’s fateful meeting with Cornelius and the subsequent mission of Paul to the Gentiles of the diaspora, Jews remained in total control of the “Jesus movement” within Judaism until the fall of Jerusalem and the scattering of the vast majority of the Jewish population among the nations (there has always been a remnant of Jews living in the Land). It is rumored that there were Jews in synagogues acknowledging Yeshua as Messiah into the second, third, and possibly even up to the fifth century CE or later.

Rabbi Joshua Brumbach wrote a blog post called Rabbis Who Thought for Themselves which records the lives of a number of prominent 19th century Rabbis who all came to the knowledge and faith of the Messiah in the person of Yeshua (Jesus), and we know of a remnant of Jews in the 21st century who also have come to faith and yet have lives that are completely consistent with modern Jewish halakhah.

At no one point in history will you find the quintessential moment where you can say “that is the true Judaism” or for that matter, “that is the true Christianity.” Humanity in all our forms has been struggling with our relationship with God, what it means, and how to live it out since the days when God walked with Adam in the Garden. We never get it quite right because we live in a broken world and our vision of who we are, who God is, and what it all means is fractured and distorted, even with the Spirit of God residing with us as a guide.

We can look at the mistakes we have made and are making even now, but we cannot say that “at such and thus time, we got it all right.” We never got it right, we just made different mistakes. But faith and devotion have been a constant thread running through the tapestry and that is what we can find tied to our own heartstrings. We can then grab hold of that thread and pull ourselves along the line, touching the lives of the saints and tzaddikim who came before us, who like us, got some things right and some things wrong, but who like us, did their very best to serve the God of Heaven.

We can look at the mistakes we have made and are making even now, but we cannot say that “at such and thus time, we got it all right.” We never got it right, we just made different mistakes. But faith and devotion have been a constant thread running through the tapestry and that is what we can find tied to our own heartstrings. We can then grab hold of that thread and pull ourselves along the line, touching the lives of the saints and tzaddikim who came before us, who like us, got some things right and some things wrong, but who like us, did their very best to serve the God of Heaven.

It’s easy to point a finger at history and at men who have been dead for hundreds or thousands of years, and vilify them in order to make ourselves look better, but in reality, they were no different from us in the important ways of how human beings work. Our only constant is love of God and of each other. We look to God to be the unchanging part of our own ever-changing universe. And we wait for the day when King Messiah will stand before Israel in Jerusalem and before the body of believers from the nations, and read the Torah aloud, and we will all hear his voice, and we will all know that we are his.