It is very difficult to fathom how two opposing opinions can both be correct. The Ritva explains this in a wondrous manner: “When Moshe received the Torah at Sinai, God provided him with forty-nine perspectives to declare a matter pure, and forty-nine to declare it impure. Moshe Rabbeinu asked, ‘Master of the universe, why are these necessary?’ God answered, ‘So that they should be transmitted to the sages of every generation, that the law will be determined by them in accordance with the needs of their time.'”

It is very difficult to fathom how two opposing opinions can both be correct. The Ritva explains this in a wondrous manner: “When Moshe received the Torah at Sinai, God provided him with forty-nine perspectives to declare a matter pure, and forty-nine to declare it impure. Moshe Rabbeinu asked, ‘Master of the universe, why are these necessary?’ God answered, ‘So that they should be transmitted to the sages of every generation, that the law will be determined by them in accordance with the needs of their time.'”

This teaches that there are many valid paths to genuine Torah observance, all of which were received by Moshe on Sinai. But of course not all statements made are the words of the living God. As we find on today’s daf, sometimes a statement thought to be a mishnah is no mishnah at all. This means that sometimes what appears to be part of the chain of tradition is actually not and needs to be clarified as such.

Rav Menachem Mendel of Rimanov, zt”l, explains how the baalei mishnah reached a state in which they could draw down an authentic mishnah. “The baalei ha’mishnah explain how the oral Torah emerges from the written Torah. They could only draw down a genuine mishnah by completely nullifying all of their physical senses and immersing themselves absolutely in learning Torah. Once they reached this state they touched the inner essence of Torah and could determine the halachah and set down various mishnayos. When the sages perceived that a certain statement was not reached through this arduous process they declared it incorrect.

Daf Yomi Digest

Stories Off the Daf

“This is Not a Mishnah!”

Bechoros 56

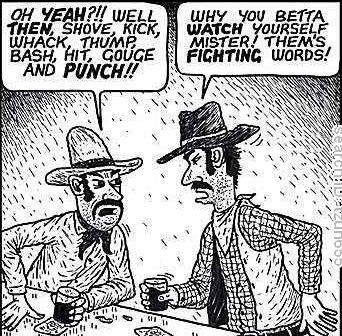

Ohmygosh! What did I just say?

This teaches that there are many valid paths to genuine Torah observance, all of which were received by Moshe on Sinai.

That statement is bound to cause something of a stir in various religious circles. It is doubtful that Christianity will accept that there are many valid paths to genuine obedience to God since we have the Master’s own words saying that there is only one way to the Father, and that is through the Son (John 14:6). Of course this is midrash we’re talking about, so it’s not as if we have to believe the “conversation” between Moses and God actually took place as recorded in our “story off the daf”. I seriously doubt that many people participating in the “Messianic” movement will be enthusiastic about this midrash either, since most of the arguments I see in the blogosphere are about obeying the Torah in only one possible way.

That, of course, doesn’t make a lot of sense from a Jewish perspective, because there really is more than one way to perform a mitzvah, depending on various circumstances. For instance, how Askenazi Jews perform some of the mitzvot and how Sephardic Jews perform those mitzvot may vary drastically. And while there may be some debate between those two groups, no one is suggesting that the Ashkenazi are the only ones who “do it right” and that the Sephardic Jews “do it wrong”…or vice versa. And frankly, even if that suggestion exists, it’s not enough to compel one group or the other to change their traditions. How a Jew performs the mitzvot and understands his or her duty to God is largely based on tradition.

But how can the midrash dare to quote a conversation between Moses and God that, in all likelihood, never took place? Remember what I said in The Rabbinization of Abraham. In order to carry the Torah forward with Judaism in the centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple, Talmudic Judaism found it necessary to “refactor” the past, projecting the view of the Rabbis of the Common Era back onto Abraham and Moses. You and I may not find this “refactoring” to be accurate or factual, but if you understand the function and purpose of Chasidic Tales, you’ll understand that many great and important truths can and must be transmitted without necessarily being based totally on fact. Christians have a tough time understanding this, but it is also likely that not everything (hold on to your hats) in the Gospel accounts of the days of Jesus is literal fact.

Did that surprise you? If you think about it for a few minutes, it probably won’t.

(I should say that this point that when I realized this, I went into a crisis of faith and struggled a great deal with the idea that my faith was based on a book that was neither a legal document in full, or a newspaper reporter’s account of the “facts”).

If you don’t believe me, pop over to Derek Leman’s blog and read this write up, Passover, Last Supper, Crucifixion: 2011 Notes, Part 2. Leman illustrates in no-nonsense terms how the different Gospel versions of the Master’s death cannot be reconciled with each other, no matter how much literary and scriptural “slight of hand” you choose to employ.

So why shouldn’t we use midrash to understand mishnah and scripture? Perhaps they are useful tools after all.

This brings us back to the idea that there may be more than one way to obey God. This brings us back to the idea that there may be one way for a Jew to obey God relative to the Messiah and Torah, and a different but still correct way for a Gentile disciple of the Master to obey God. Are these two covenants? That suggestion is usually viewed with horror, especially if taken to the extreme and seen as “the Jews have Moses and the Gentiles have Jesus.” I’m not suggesting that (although the dynamics involving religious Jews who are not “Messianic” is certainly complex). I’m suggesting that for Jews who are disciples of Jesus and for Gentiles who are disciples of Jesus, there may be two paths to obedience based on identity and “covenant connection” (Jews were at Sinai and any Gentiles who were also present were absorbed into the Children of Israel, probably within three generations). The Jews have the Mosaic covenant connection which was not designed to accommodate non-Jews except for those Gentiles who were on the “multi-generational conversion track”. The Messianic covenant is unique in that it accommodates Jewish identity, allowing “Messianic Jews” to remain Jews (this is all heavily flavored by my opinions here) and also it allows Gentiles to enter into a covenant relationship with God, being “grafted in” as “wild branches” onto the “civilized tree” (note that the grafted in wild branches remain wild for the lifetime of the tree and don’t “morph” into civilized branches) and they can still remain Gentiles…forever.

This brings us back to the idea that there may be more than one way to obey God. This brings us back to the idea that there may be one way for a Jew to obey God relative to the Messiah and Torah, and a different but still correct way for a Gentile disciple of the Master to obey God. Are these two covenants? That suggestion is usually viewed with horror, especially if taken to the extreme and seen as “the Jews have Moses and the Gentiles have Jesus.” I’m not suggesting that (although the dynamics involving religious Jews who are not “Messianic” is certainly complex). I’m suggesting that for Jews who are disciples of Jesus and for Gentiles who are disciples of Jesus, there may be two paths to obedience based on identity and “covenant connection” (Jews were at Sinai and any Gentiles who were also present were absorbed into the Children of Israel, probably within three generations). The Jews have the Mosaic covenant connection which was not designed to accommodate non-Jews except for those Gentiles who were on the “multi-generational conversion track”. The Messianic covenant is unique in that it accommodates Jewish identity, allowing “Messianic Jews” to remain Jews (this is all heavily flavored by my opinions here) and also it allows Gentiles to enter into a covenant relationship with God, being “grafted in” as “wild branches” onto the “civilized tree” (note that the grafted in wild branches remain wild for the lifetime of the tree and don’t “morph” into civilized branches) and they can still remain Gentiles…forever.

Now we come back to the key phrase in today’s midrash.

This teaches that there are many valid paths to genuine Torah observance, all of which were received by Moshe on Sinai.

If you’re a non-Jew and you’re upset with how someone else is interpreting Gentile “Torah obedience”, figuring your way is right and their way is wrong, hold up a minute. First off, you Gentiles may not have any sort of “Torah obedience” based on the Mosaic covenant, so you may be traveling on the wrong path all together. Second, even within Judaism, as I previously mentioned, there is more than one accepted halacha to performing the mitzvot.

Hopefully, this will shake up someone’s moral certitude the next time they get into an Internet argument about how the Torah is supposed to be obeyed. If you continue to do your studying and are honest about it, you may find your assumptions challenged. The great Hillel was the master of teaching this lesson to potential converts, as recorded at SaratogaChabad.org.

Let us use the famous story of Shammai, Hillel and the three converts (Shabbos 31) to demonstrate the fusion of Halacha and Aggadah,: A gentile once came to Shammai, and wanted to convert to Judaism. But he insisted on learning the whole Torah while standing on one foot. Shammai rejected him, so he went to Hillel, who taught him: “What you dislike, do not do to your friend. That is the basis of the Torah. The rest is commentary; go and learn!” Another gentile who accepted only the Written Torah, came to convert. Shammai refused, so he went to Hillel. The first day, Hillel taught him the correct order of the Hebrew Alphabet. The next day he reversed the letters. The convert was confused:”But yesterday you said the opposite!?” Said Hillel: “You now see that the Written Word alone is insufficient. We need the Oral Tradition to explain G-d’s Word.” A third gentile wanted to convert so he could become the High Priest, and wear the Priestly garments. Shammai said no, but Hillel accepted him. After studying, he realized that even David, the King of Israel, did not qualify as a cohen, not being a descendant of Aaron

The convert was not just acting silly by standing on one foot; he was actually symbolizing his quest for true unity. This gentile had left behind a confusing plethora of pagan gods and multiple deities. He searched and finally found Monotheism, One Torah and One G-d, wanting to live by a single unifying principle, the ‘one foot’ on which all else stands. Hillel taught him that the underlying principle that unites all is Jewish Love. The second convert, had rejected the other man-made religions as human concoctions, was attracted to the Divine Torah, which consisted solely of G-d’s word. He was shocked to find that we follow a Rabbinical tradition. He wasn’t being rebellious, but sincerely asking a valid question; “I wish to observe G-d’s word alone, not any human additions.” Hillel creatively showed him that the two Torahs are not two separate systems, but are one and the same. The written word and the oral traditions complement each other. It is as basic as the Aleph Bais, where you can’t have one without the other. Indeed, the Torah itself bids us to follow the enactments of the sages. The third convert, disillusioned with pagan shallowness, aimed for a higher meaning to life. He yearned to reach the highest level, assuming that being a High Priest is the ultimate spiritual fulfillment.

Hillel didn’t just chase these would-be converts away, he (seemingly) accepted them on their own terms but allowed them to study and discover their own errors. Once they did so, they put aside their original assumptions and realized that in order to convert, they had to accept the Torah as it was within the Jewish framework of their day.

Hillel didn’t just chase these would-be converts away, he (seemingly) accepted them on their own terms but allowed them to study and discover their own errors. Once they did so, they put aside their original assumptions and realized that in order to convert, they had to accept the Torah as it was within the Jewish framework of their day.

May God grant us the ability, wisdom, and will do to the same.