Thus says the Lord,

“Preserve justice and do righteousness,

For My salvation is about to come

And My righteousness to be revealed.

“How blessed is the man who does this,

And the son of man who takes hold of it;

Who keeps from profaning the sabbath,

And keeps his hand from doing any evil.”

Let not the foreigner who has joined himself to the Lord say,

“The Lord will surely separate me from His people.”

Nor let the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.”For thus says the Lord,

“To the eunuchs who keep My sabbaths,

And choose what pleases Me,

And hold fast My covenant,

To them I will give in My house and within My walls a memorial,

And a name better than that of sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name which will not be cut off.

“Also the foreigner who join themselves to the Lord,

To minister to Him, and to love the name of the Lord,

To be His servants, every one who keeps from profaning the sabbath and holds fast My covenant;

Even those I will bring to My holy mountain

And make them joyful in My house of prayer.

Their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be acceptable on My altar; for My house will be called a house of prayer for all the peoples.”

The Lord God, who gathers the dispersed of Israel, declares,

“Yet others I will gather to them, to those already gathered.”–Isaiah 56:1-8 (NASB)

I made a comment in one of my recent blog posts that having rendered a simple, basic definition for living a life of holiness, what else should I write about? After all, once the path is before me, my only job is to walk the path, not write endless commentaries about it.

But somewhere in my comments, I also mentioned the need to address, among other things, certain sections of Isaiah 56, from which I quoted above. I have largely defined a life of holiness for a non-Jewish disciple of Rav Yeshua (Jesus Christ) apart from the vast majority of Jewish lifestyle and religious observance practices. To live a life of holiness and devotion to God, it is my opinion that we non-Jews have no obligation observe the traditional mitzvot associated with religious Jewish people.

But we encounter a few “problems” in the above-quoted passage from Isaiah. Even leaving out the sections that relate to “eunuchs,” “the foreigner” is not to consider himself (or herself) as being separated from His people (presumably Israel). Further, foreigners who join themselves to the Lord do so, in part, by not “profaning the sabbath” (otherwise translated as “guarding” the sabbath) and by holding fast to “My [God’s] covenant.”

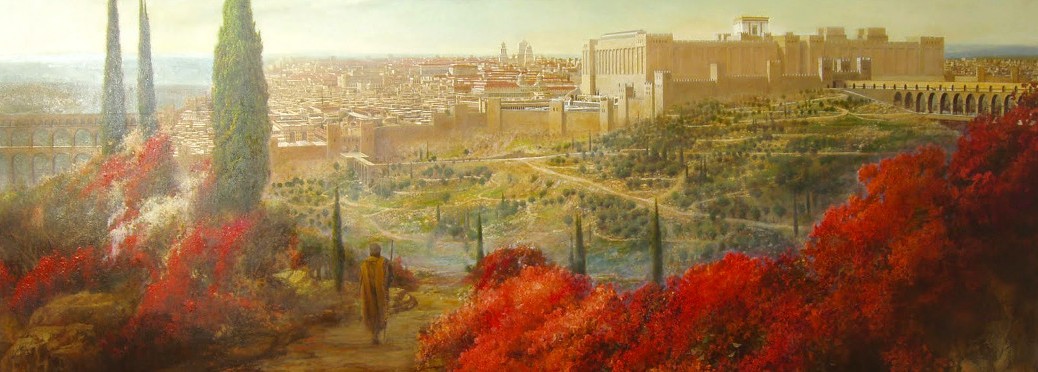

In addition, the foreigner will be joyful in Hashem’s house of prayer (the Temple) and it will be called “a house of prayer for all peoples,” which seems to indicate the people of every nation.

In addition, the foreigner will be joyful in Hashem’s house of prayer (the Temple) and it will be called “a house of prayer for all peoples,” which seems to indicate the people of every nation.

In doing some research for today’s “meditation,” I discovered I’ve written about the Book of Isaiah before.

That was a sweeping panorama of the entire book (click the link to read it all), but of Isaiah 56, I wrote only this:

Isaiah 56 is the first time in the entire sixty-six chapter book that says anything specifically about how the nations will serve God. I was wondering if the word “foreigner” in verse 3 might indicate “resident alien” and somehow distinguish between Gentile disciples of the Messiah and the rest of the nations, which could bolster the claim of some that these “foreigners” merge with national Israel, but these foreigners, also mentioned as such in verse 6, are contrasted with “the dispersed of Israel” referenced in verse 8.

And…

And the foreigners who join themselves to Hashem to serve Him and to love the Name of Hashem to become servants unto Him, all who guard the Sabbath against desecration, and grasp my covenant tightly…

–Isaiah 56:6

This is the main indication that foreigners among Israel will also observe or at least “guard” the Sabbath (some Jewish sages draw a distinction between how Israel “keeps” and the nations “guard”), and the question then becomes, grasp what covenant tightly? Is this a reference to some of the “one law” sections of the Torah that laid out a limited requirement of observance of some of the mitzvot for resident aliens which includes Shabbat?

I won’t attempt to answer that now since I want to continue with a panoramic view of Isaiah in terms of the relationship between Israel and the nations (and since it requires a great deal more study and attention).

I’m reminded that in very ancient times, the “resident alien,” a Gentile who intended for his/her descendants in the third generation and beyond, to assimilate into Israel, losing all association with their non-Israelite ancestors, had a limited duty to obey just certain portions of the Torah mitzvot in the same way as a native Israelite.

The “one law” didn’t cover all of the mitzvot, but only a small subsection, such as a limited guarding of the Shabbat, which I mentioned above.

The “one law” didn’t cover all of the mitzvot, but only a small subsection, such as a limited guarding of the Shabbat, which I mentioned above.

Also, my understanding of the legal and scriptural mechanics behind the Acts 15 Jerusalem letter edict, is that the non-Jewish disciple of Rav Yeshua was to be considered, in some manner, a “resident alien” within the Jewish religious community of “the Way,” Jewish Yeshua-believers.

Putting all this together, we may infer some limited form of Torah observance for the non-Jew in Messiah, but beyond what we have before us so far, exactly what that entails may not be entirely clear.

Although the statement in Isaiah 56 saying that the foreigner was to “hold fast My covenant” seems general, there are only two specific areas mentioned: sabbath and prayer.

Regarding the Shabbat and Isaiah 56, I’ve written twice. The first mention is from My Personal Shabbos Project:

Of course, as I said before, I think there’s a certain amount of justification for non-Jews observing the Shabbat in some fashion based both on Genesis 2 in honoring God as Creator, and Isaiah 56 which predicts world-wide Shabbat observance in the Messianic Kingdom.

The second mention was from a companion blog post called Messianic Jewish Shabbat Observance and the Gentile where I mention using a particular Shabbat “siddur” that was specifically prepared for “Messianic Gentiles,” and this references Isaiah 56:7

This seems to bridge between the first specific item, Shabbat, and the second, which is prayer. I wrote of prayer and Isaiah 56 almost a year ago in this review of a sermon series:

Judaism makes a distinction between corporate and personal prayer, and man was meant to engage in both. Participation in the Jewish prayer services, at least in some small manner, is as if you have participated in the Temple services, which as Lancaster mentioned, is quite a privilege for a Messianic Gentile. It also summons the prophesy that God’s Temple will be a house of prayer for all nations (Isaiah 56:7, Matthew 21:13).

In addition to all of the above, we have this statement made by King Solomon as part of his dedication to the newly built Temple:

“Also concerning the foreigner who is not of Your people Israel, when he comes from a far country for Your name’s sake (for they will hear of Your great name and Your mighty hand, and of Your outstretched arm); when he comes and prays toward this house, hear in heaven Your dwelling place, and do according to all for which the foreigner calls to You, in order that all the peoples of the earth may know Your name, to fear You, as do Your people Israel, and that they may know that this house which I have built is called by Your name.”

–I Kings 8:41-43

This doesn’t seem to be limited to the resident alien temporarily or even permanently dwelling among Israel, but includes any non-Jewish visitor who, for the sake of God’s great Name, comes to Jerusalem and prays toward (facing) the Temple.

Of all the commandments incumbent upon both the Jew and the Gentile believer, it seems that prayer is to be shared among all peoples.

But what about Shabbat or, for that matter, any of the other commandments?

I want to limit myself (mostly) to Isaiah 56 since it seems to be a sticking spot for many non-Jews who believe it acts as a “smoking gun” pointing toward the universal application of all of the Torah commandments to everyone, effectively obliterating everything God promised about Jewish distinctiveness.

Since non-Jews are so prominently mentioned in this chapter, I decided to see what (non-Messianic) Jews thought of this.

The easiest (though highly limited) way to do so was to look up this portion of scripture online at Chabad.org see read Rashi’s commentary on the matter.

Here’s verse 3:

Now let not the foreigner who joined the Lord, say, “The Lord will surely separate me from His people,” and let not the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.”

Here’s Rashi’s commentary on the verse:

“The Lord will surely separate me from His people,”: Why should I become converted? Will not the Holy One, blessed be He, separate me from His people when He pays their reward.

My best guess at the meaning of this statement is that the Gentile should not convert to Judaism since, when Hashem gives Israel its reward, won’t the convert be set apart from His people?

But I’m almost certainly reading that statement wrong. It makes no sense to me, since converts, according to the Torah, are to be considered as identical to the native-born. I don’t have an answer for this one.

The other relevant verses are 6 through 8, and here’s Rashi’s only commentary on them:

for all peoples: Not only for Israel, but also for the proselytes.

I will yet gather: of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] of the nations) who will convert and join them.

together with his gathered ones: In addition to the gathered ones of Israel.

All the beasts of the field: All the proselytes of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] All the nations) come and draw near to Me, and you shall devour all the beasts in the forest, the mighty of the heathens ([Mss. and K’li Paz:] the mighty of the nations) who hardened their heart and refrained from converting.

Referring to “foreigners” as proselytes or non-Jewish converts to Judaism is rather predictable and an easy way to avoid the thorny problem of Gentile observance of Shabbos or some other sort of association with Israel.

The last commentary seems to make some mention of “heathens,” possibly meaning that, in the end, Jews and non-Jews will turn to God, but ultimately, it seems, Rashi expects all non-Jews to convert to Judaism as their only means to become reconciled with Hashem.

My general knowledge of Jewish belief (and I suspect I’ll be corrected here) indicates that non-Jews will exist in Messianic days and those devoted to Hashem will be Noahides or God-fearers, just as we have those populations in synagogues today. They will have repented of their devotion to “foreign gods,” which from a more traditional Jewish perspective, will include (former) Christians.

So without further convincing proofs, I’m at an impasse. I can definitively state that part of a life of holiness for both a Jew and Gentile is prayer to the Most High God. Of course, that should be a no-brainer.

So without further convincing proofs, I’m at an impasse. I can definitively state that part of a life of holiness for both a Jew and Gentile is prayer to the Most High God. Of course, that should be a no-brainer.

The Shabbat is a bit more up in the air. While I can’t see any real objection to a non-Jew observing a Shabbat in some manner, there doesn’t seem to be a clear-cut commandment. In Messianic Days, Shabbat may well be observed in a more universal manner, though the exact praxis between Jews and Gentiles likely won’t be identical.

As the discussion in How Will We Live in the Bilateral Messianic Kingdom indicated, while the vast majority of the Earth’s Jewish population may reside in the nation of Israel in Messianic Days, there may be some ambassadors assigned to each of the nations, and thus, there may be an application of the Shabbat in the nations for their sake and for the sake of Jews traveling abroad for business or leisure reasons.

I also can’t rule out a wider application of Shabbat observance for the Gentile in acknowledgement of God as the Creator of the Universe, which we see in Genesis 2:3:

Then God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made.

That’s supposition on my part, but it’s not entirely out of the ballpark.

In any event, Isaiah 56 doesn’t give us as much detail about non-Jews in relation to the Torah as some folks might think. Pray? Yes. Pray toward the Temple in Jerusalem, even if you are outside Israel? Maybe. Couldn’t hurt.

Observe the Shabbat? Maybe in some fashion. I think this part will become more clear once Messiah returns as King, establishes himself on his throne in Jerusalem, and then illuminates the world.

Observe the Shabbat? Maybe in some fashion. I think this part will become more clear once Messiah returns as King, establishes himself on his throne in Jerusalem, and then illuminates the world.

In terms of what I’ve written before, prayer should already be part of a simple life of holiness, so Isaiah 56 doesn’t add to this. Some form of Shabbat observance is allowable but may not be absolutely required for the Gentile in the present age. Isaiah 56 doesn’t make it clear that a Gentile “guarding” or not “profaning” the Shabbat is also “observing” it, and even if we do observe, there’s still not an indication that such observance would be identical to current Jewish praxis.

Bottom line: when in doubt stick to the basics.