While the apostles in Jerusalem debated about whether or not to receive Cornelius the God-fearer and his household into the Way, the message was already spreading to Gentiles in other places. Gentiles in the faraway kingdoms of Adiabene and Osroene were learning about the God of the Jews and His Messiah.

While the apostles in Jerusalem debated about whether or not to receive Cornelius the God-fearer and his household into the Way, the message was already spreading to Gentiles in other places. Gentiles in the faraway kingdoms of Adiabene and Osroene were learning about the God of the Jews and His Messiah.

The Syriac-speaking kingdom of Adiabene, with its capital at Arbela (modern Arbil, Iraq), straddled the highlands of what is today the Kurdish areas of Iraq, Armenia, and northern Iran. Adiabene was part of the Assyrian province of the Parthian Empire.

Torah Club, Volume 6: Chronicles of the Apostles from First Fruits of Zion (FFOZ)

Torah Portion Miketz (“From the end”) (pg 259)

Commentary on Acts 11:19-20

Additional Reading: Josephus, Antiquities 20:17-96/ii-iv; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 1.13

One of the objections I read about Volume 6 of Torah Club recently was its use of non-Biblical information sources. Apparently, this is a big deal for some people who previously found the Torah Club material very illuminating. I guess author D. Thomas Lancaster isn’t supposed to consider other historical documentation when writing about the late Second Temple period and the events surrounding the early church.

That’s pretty strange, since all competent historians and historical theologians review a wide variety of documents and artifacts when studying a specific topic and those documents are frequently referenced by such scholars when they publish their findings. All you have to do is read blogs by theologians such as the one maintained by New Testament scholar Larry Hurtado to see this process in operation. (Additionally, there are many scholars and students who caution us regarding taking everything we read in the Bible as literal fact)

King Abennerig welcomed the young prince into his court and the capital city of Charax Spasinu. Izates quickly won the affection of his host who gave him his daughter Samachos (Sumaqa, Aramaic for “Red”) in marriage and appointed him governor of one of his provinces.

Izates soon learned that Samachos had fallen under the influence of a Jewish teacher. She introduced him to a Jew named Ananias (Chananyah) and the religion of Judaism.

-Lancaster, pg 250

The conversion of Izates to Judaism is a rather well-known story , and it occurred more or less at the same time the Jewish apostle Paul was spreading the Gospel among the Jews and Gentiles in the diaspora. We know that Izates became a God-fearer and student of Judaism and eventually became circumcised and converted to Judaism, however, according to Lancaster, there is some speculation as to whether or not Ananias might have been a disciple of Jesus and a member of the Way. Some have even thought that Ananias might have been the same person we find here.

Now there was a disciple at Damascus named Ananias. The Lord said to him in a vision, “Ananias.” And he said, “Here I am, Lord.” And the Lord said to him, “Rise and go to the street called Straight, and at the house of Judas look for a man of Tarsus named Saul, for behold, he is praying, and he has seen in a vision a man named Ananias come in and lay his hands on him so that he might regain his sight.”

–Acts 9:10-12 (ESV)

But unless there’s something more compelling than these two individuals having the same name, I’m not inclined to automatically believe they are the same person. Lancaster seems to take the reader down a particular road, not presenting it as fact, but rather as interesting speculation.

Readers of Josephus have often wondered if Ananias might not have been a believer. His type of active and aggressive proselytism seems more consistent with the disciples of Yeshua than it does with the rest of first-century Judaism. Like the Pauline school of thought, Ananias did not encourage Izates or any of his converts to undergo a formal conversion to become Jewish. He counseled Izates against doing so and encouraged him to remain uncircumcised.

Robert Eisenman speculates that Ananias the merchant is the same as Ananias of Damascus whom Paul encountered. Eisenman also mentions Armenian Christian sources that claim Izates and his mother converted to Christianity – not Judaism. At that early time, “Christianity” was still a sect of Judaism, not an independent religion that could have been defined outside of Judaism. Josephus would not have made the distinction.

Even if Ananias was not a believer or one of the apostles, he taught a type of Judaism for Gentiles similar to the teaching of the apostles.

Like Paul’s converts, Izates became an adherent of Judaism but not Jewish – not a proselyte either. He became a God-fearer.

-Lancaster, pg 250

This certainly throws a monkey-wrench into the machine. Was Ananias a follower of the Way or not? Even if he wasn’t, he (apparently) was not converting Gentiles to Judaism but instead, going out of his way to make God-fearers and to teach them Judaism.

This certainly throws a monkey-wrench into the machine. Was Ananias a follower of the Way or not? Even if he wasn’t, he (apparently) was not converting Gentiles to Judaism but instead, going out of his way to make God-fearers and to teach them Judaism.

Again, and I can’t stress this strongly enough, all this is speculation and should be taken with more than a grain of salt. But then again, we have a lack of information regarding the “early church” and the spread of the various Judaisms of that day through their “apostles,” so when operating in a vacuum, we tend to fill the gap with our imagination, stringing the bits of scattered facts together with the thread of our personalities.

Izates ultimately ascended to the throne and his mother also became a student of Judaism (actually, before Izates did and without his knowledge). But while Ananias was content and even insistent that the King and his household not convert to Judaism, other Jews were not.

Sometime later, however, a certain Galilean Jew named Eleazar arrived in Adiabene. He was a sage and Torah scholar. King Izates heard about the arrival of the sage and invited him to visit the royal court. When Eleazar entered the palace, he found Izates seated, reading the Torah of Moses. Like Paul’s theological opponents, Eleazar of Galilee dismissed the God-fearer status as illegitimate. He had some sharp words for the uncircumcised king:

Have you never considered, O King, that you unjustly violate the rule of those laws you are studying, and you are an insult to God himself by omitting to be circumcised. For you should not merely study the commandments; more importantly, you should do what they tell you to do. How long will you continue to be uncircumcised? But if you have not yet read the law about circumcision, and if you are unaware of how great an impiety you are guilty of by neglecting it, read it now.

The king sent immediately for a surgeon. Izates completed his formal conversion to Judaism at Eleazar’s behest and under his supervision. His mother did so as well.

-Lancaster, pg 251

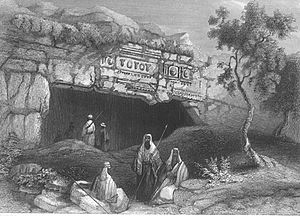

According to Lancaster’s sources, Izates and his mother Helena built palaces for themselves in Jerusalem as well as preparing tombs for themselves so after their eventual demise, they could be interned in the holy city. In fact, some part of this has been substantiated, as the “Tomb of the Kings” in East Jerusalem, north of the Old City walls, has been identified as the tomb of Queen Helena and her sons.

In reading this Torah Club commentary…

Helena submitted herself completely to the authority of the sages. Izates and Helena contributed vast sums toward the Temple…(Queen Helena) also had a golden tablet made and inscribed with the words of the vow of the bitter water for the woman suspected of adultery.

-Lancaster, pg 252

All of this is interesting to be sure, but what does it have to do with us? Even if we choose to buy the speculation that Izates and Helena were followers of the Way and converted to that particular sect of Judaism, since that time, Christianity and Judaism have diverged into radically different trajectories so that one has little to do with the other.

In the Hebrew/Jewish Roots movement and its variants, there is a particular interest in just how non-Jews were integrated into that sect of Judaism that eventually became known as “Christianity.” I mentioned in Part 1 and Part 2 of my previous commentary on the Torah Club that the “conversion” of Cornelius and his household omitted any actual conversion to Judaism. Like Izates, Cornelius was taught Judaism but not circumcised. There’s no evidence that Peter deliberately discouraged Cornelius from a full conversion, but we don’t know what sort of decision making process occurred among the apostles between Peter’s encounter with Cornelius and Ananias’ encounter with Izates (and we have no real reason to assume that Ananias was also an apostle of the Way).

In the Hebrew/Jewish Roots movement and its variants, there is a particular interest in just how non-Jews were integrated into that sect of Judaism that eventually became known as “Christianity.” I mentioned in Part 1 and Part 2 of my previous commentary on the Torah Club that the “conversion” of Cornelius and his household omitted any actual conversion to Judaism. Like Izates, Cornelius was taught Judaism but not circumcised. There’s no evidence that Peter deliberately discouraged Cornelius from a full conversion, but we don’t know what sort of decision making process occurred among the apostles between Peter’s encounter with Cornelius and Ananias’ encounter with Izates (and we have no real reason to assume that Ananias was also an apostle of the Way).

What we do know is that Izates did keep significant portions of Torah, adhering to Jewish customs and practices which we assume could have included keeping kosher, observing Shabbat, and performing the daily prayers. We certainly have evidence that Izates and Helena, before and after formal conversion, were generous to the Jews and donated to the Temple. This includes Helena purchasing vast quantities of grain and paying for it to be transported on ships to feed the hungry among Israel when she discovered a famine in Jerusalem and Judea (I can’t help but recall Joseph in Egypt in this instance).

Cornelius was also a devout man who observed the set times of prayer, donated funds for the benefit of the Jews, and that these acts were considered by God as a memorial (sacrifice) before him (see Acts 10:1-4). Given that Peter and the other Jews in his party spent several days in the home of Cornelius and likely ate with him and his household, Cornelius probably had kosher food available and maybe even kept a form of kosher himself.

In all this we can construct a model of what it was like (though facts are sparse) to be an early Gentile participant in the sects of Judaism including the Way. We have examples of Gentiles studying Torah and observing some of the mitzvot and either being discouraged when they expressed a desire to convert (Izates) or the option of conversion simply never arising (Cornelius). As we saw above, even Josephus was unlikely to have considered “the Way” as anything separate from the other Jewish sects of the late first century in which some Gentiles were partaking. It is on this basis that many 21st century Gentile believers are adopting some of the modern expressions of the mitzvot, including forms of observing Shabbat, keeping kosher, and davening at the set times of prayer.

Although 2,000 years have passed, there seems to be a hunger among some believers to try to recapture the flavor of the early Gentile disciples of the Way in order to access something they believe is more authentic about their faith. But while observing some of the mitzvot made perfect sense in a religious practice that was completely Jewish in the days of Peter and Paul, does it make any sort of sense now?

I don’t know. Theologically, I don’t think we can really say “no,” since we have precedent in the Bible and other sources, but on the other hand, the Bible and these other sources do not give us a clear picture of Gentiles who had not undergone full conversion observing the mitzvot in the same manner as the born-Jew. In fact, we see in the example of Izates and Eleazar, a definite Jewish objection to an uncircumcised Gentile studying the Torah without actually obeying it by converting to Judaism. This certainly suggests that some sects of Judaism required a Gentile to undergo full conversion prior to observance of the mitzvot, which apparently included even studying the Torah of Moses.

But as I’ve said repeatedly, information is sketchy. We’re not that certain of our facts. Which is a very, very good reason for people who believe they are certain that modern Christians must observe the full Torah mitzvot like a born-Jew or Jewish convert to re-examine their material and their assumptions. I believe Lancaster in this Torah Club commentary took liberties with his information and made certain assumptions to stimulate the imagination of his audience and to get us thinking “outside of the box.” But that’s a long way from saying that his assumptions are facts and that we must treat them as such, altering our faith and our observance accordingly.

It’s interesting and even fun to take what little information we have available to us about the early church and to play a game of “what if.” It’s erroneous and even dangerous to forget that we’re just imagining and to believe the stories we’re building for ourselves. A life of faith is a life of exploration and discovery, but determining the difference between a bit of iron pyrite and a gold nugget is quite a bit harder than we might think.

It’s interesting and even fun to take what little information we have available to us about the early church and to play a game of “what if.” It’s erroneous and even dangerous to forget that we’re just imagining and to believe the stories we’re building for ourselves. A life of faith is a life of exploration and discovery, but determining the difference between a bit of iron pyrite and a gold nugget is quite a bit harder than we might think.

A final word. If you are a Christian who feels drawn to certain of the mitzvot, if you are inspired by davening with a siddur, by observing the set times of prayer, by lighting the Shabbos candles, by giving tzedakah to the poor among Israel, I can see no reason to object to this. It is what Cornelius would have done. It is what Izates and Helena would have done. But unless you undergo formal conversion through a recognized Jewish authority (which includes circumcision if you are male), it does not make you Jewish nor does it obligate you to keep all of the Torah mitzvot.

While history records that King Izates and his mother fully converted to Judaism and accepted a life of Torah upon themselves, we have no knowledge that Cornelius or any of his household also did so. While Cornelius and his household observed certain of the mitzvot, we have no information that he considered this observance an “obligation” or a “right” but simply a matter of drawing nearer to the God of the Jews, who he came to know as the One God. If we choose to look at our own religious practice as a “drawing nearer” so that we may know God rather than something that is “owed” to us, then perhaps God will hear our prayers and bring us into His Presence in peace.