And you shall love the Lord your G-d. with all your ‘me’od’ –Deuteronomy 6:5

And you shall love the Lord your G-d. with all your ‘me’od’ –Deuteronomy 6:5

The word me’od has many meanings. It serves as the etymological root for ‘measure’ (midah), ‘thank’ ( modeh), and ‘very much’ ( me’od). Using all three meanings in its interpretation of the above verse, the Talmud states:

“A person is obligated to bless G-d for the bad just as he blesses Him for the good, as it is written: ‘And you shall love the Lord your G-d. with all your me’od’ – for every measure which He measures out to you, thank Him very, very much.” -The Talmud, Brachos 54a

The name of this week’s Torah Portion, Va’etchanan means “and he pleaded”, referring to Moshe’s (Moses’) pleading with God to allow him to live and to lead the Children of Israel into the Land of Canaan, even after God had decreed that Moses should die. We learn from the Mishnah on Va’etchanan, that we should bless God for everything that happens in our lives, the good and bad alike. As we see in the following example, that’s not an easy thing to even consider, let alone perform:

A man once came to Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov with a question: “The Talmud tells us that one is to ‘bless G-d for the bad just as he blesses Him for the good.’ How is this humanly possible? Had our sages said that one must accept without complaint or bitterness whatever is ordained from Heaven – this I can understand. I can even accept that, ultimately, everything is for the good, and that we are to bless and thank G-d also for the seemingly negative developments in our lives. But how can a human being possibly react to what he experiences as bad in exactly the same way he responds to the perceptibly good? How can a person be as grateful for his troubles as he is for his joys?”

-Rabbi Yanki Tauber

“A Matter of Perspective”

Chabad.org

It’s easy to imagine being the man who is trying to get a seemingly impossible answer from the Baal Shem Tov. Whenever good happens in our lives, if we have any sense of God in our lives at all, we thank Him with all our heart and being for His goodness and His providence. When tragedy and disaster strike on the other hand, blessing God becomes much more difficult. Most of us do not respond like Job, apparently, not even Moses.

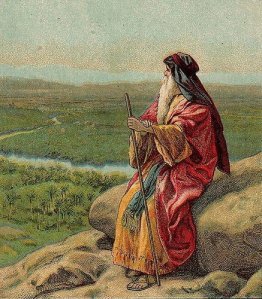

I pleaded with the Lord at that time, saying, “O Lord God, You who let Your servant see the first works of Your greatness and Your mighty hand, You whose powerful deeds no god in heaven or on earth can equal! Let me, I pray, cross over and see the good land on the other side of the Jordan, that good hill country, and the Lebanon.” But the Lord was wrathful with me on your account and would not listen to me. The Lord said to me, “Enough! Never speak to Me of this matter again! Go up to the summit of Pisgah and gaze about, to the west, the north, the south, and the east. Look at it well, for you shall not go across yonder Jordan. Give Joshua his instructions, and imbue him with strength and courage, for he shall go across at the head of this people, and he shall allot to them the land that you may only see.” –Deuteronomy 3:23-28

When we pour out our heart to God, it would seem almost cruel for God to respond in this manner. Why does He treat His faithful servant Moses this way? Why is a rebuke God’s response to this type of prayer? The following is how the Rambam describes prayer, but it seems to contradict what happened between Moses and God:

The obligation [this] commandment entails is to offer supplication and prayer every day; to praise the Holy One, blessed be He, and afterwards to petition for all one’s needs with requests and supplications, and then to give praise and thanks to G-d for the goodness that He has bestowed.

The fundamental dimension of prayer is to ask G-d for our needs. The praise and thanksgiving which precede and follow these requests is merely a supplementary element of the mitzvah. A person must realize that G-d is the true source for all sustenance and blessing, and approach Him with heartfelt requests.

Often, however, we do not content ourselves with asking for our needs. We desire bounty far beyond both our needs and our deserts. We request a boon that reflects G-d’s boundless generosity. For every Jew is as dear to G-d as is an only child born to parents in their old age. And because of that inner closeness, He grants us favors that surpass our needs and our worth.

As quoted from

“Vaes’chanan: To Plead with God”

-Rabbi Eli Touger

Adapted from

Likkutei Sichos, Vol. XXII, pgs. 115-117;

Vol. XXIV, p. 28ff

However, Rabbi Touger goes on to say that pleading “is one of the ten terms used for prayer” and that “Moshe [approached G-d] in a tone of supplication, [asking] for a free gift” demonstrating that “no created being can make demands from its Creator”. It’s one thing to pour out your heart to God with your needs and your troubles, but no man is entitled to anything from God that God Himself does not will.

However, Rabbi Touger goes on to say that pleading “is one of the ten terms used for prayer” and that “Moshe [approached G-d] in a tone of supplication, [asking] for a free gift” demonstrating that “no created being can make demands from its Creator”. It’s one thing to pour out your heart to God with your needs and your troubles, but no man is entitled to anything from God that God Himself does not will.

I don’t say this to be unkind to Moses. Certainly he was the greatest of all the Prophets, a man who spoke to God “face-to-face”, so to speak” and the most humble of men. However, he was a man and like all men, was less than perfect in the eyes of God, as we see in the incident at Meribah (Numbers 20:1-13).

But even then, it is not so wrong for Moses or for any of us to beg that God turn aside His wrath when we pray:

There is a difference of opinion among our Sages (Rosh HaShanah 17b) as to whether prayer can have an effect after a negative decree has been issued from Above, or only beforehand. The Midrash follows the view that prayer can avert a harsh decree even after it has been issued. Therefore Moshe was able to approach G-d through one of the accepted forms of prayer.

-from Rabbi Touger’s commentary

No, for all his humanity and doubtless, all his frustration, Moses prayed the way any of us would pray, that God would relent and spare him what he no doubt saw as the most anguished of consequences. In the end, did Moses bless God for not being allowed into the Land? For most of his address to the Children of Israel, Moses pleads with them, he warns them, he begs them not to disobey God. Only minutes from death, he continues to do what he has done for the past 40 years, protect the people from their own folly, from their own sin, from their own desire for destruction, with every bit of his effort. Deuteronomy 33 is his blessing to Israel and in the following and final chapter of the Torah, Moses quietly obeys, passing the mantle of leadership on to Joshua.

Then Moses climbed Mount Nebo from the plains of Moab to the top of Pisgah, across from Jericho. There the LORD showed him the whole land—from Gilead to Dan, all of Naphtali, the territory of Ephraim and Manasseh, all the land of Judah as far as the Mediterranean Sea, the Negev and the whole region from the Valley of Jericho, the City of Palms, as far as Zoar. Then the LORD said to him, “This is the land I promised on oath to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob when I said, ‘I will give it to your descendants.’ I have let you see it with your eyes, but you will not cross over into it.”

And Moses the servant of the LORD died there in Moab, as the LORD had said. –Deuteronomy 34:1-5

How very much like the one who came after him, how like the death of “The Prophet”.

He was oppressed and He was afflicted, Yet He did not open His mouth; Like a lamb that is led to slaughter, And like a sheep that is silent before its shearers, So He did not open His mouth. –Isaiah 53:7

“How can I,” he said, “unless someone explains it to me?” So he invited Philip to come up and sit with him.

This is the passage of Scripture the eunuch was reading:

“He was led like a sheep to the slaughter,

and as a lamb before its shearer is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

In his humiliation he was deprived of justice.

Who can speak of his descendants?

For his life was taken from the earth.”The eunuch asked Philip, “Tell me, please, who is the prophet talking about, himself or someone else?” Then Philip began with that very passage of Scripture and told him the good news about Jesus. –Acts 8:31-35

We can hardly blame Moses for his plea to God. We certainly don’t blame Jesus:

Going a little farther, he fell to the ground and prayed that if possible the hour might pass from him. “Abba, Father,” he said, “everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will.” –Mark 14:35-36

But Jesus did not stop at pleading with God but rather bowed to His will in all things, even suffering and death.

But Jesus did not stop at pleading with God but rather bowed to His will in all things, even suffering and death.

But what about those of us who are less than Prophets; we “ordinary people”. What about the man and his question of the Baal Shem Tov?

In this matter, the Baal Shem Tov sent the man to his disciple, Reb Zusha of Anipoli for the answer to the man’s question. Here’s the remainder of Rabbi Tauber’s narrative and the lesson we can take from Va’etchanan:

Reb Zusha received his guest warmly, and invited him to make himself at home. The visitor decided to observe Reb Zusha’s conduct before posing his question and before long concluded that his host truly exemplified the talmudic dictum which so puzzled him. He couldn’t think of anyone who suffered more hardship in his life than did Reb Zusha. A frightful pauper, there was never enough to eat in Reb Zusha’s home, and his family was beset with all sorts of afflictions and illnesses. Yet the man was forever good-humored and cheerful, and constantly expressing his gratitude to the Almighty for all His kindness.

But what was is his secret? How does he do it? The visitor finally decided to pose his question.

So one day, he said to his host: “I wish to ask you something. In fact, this is the purpose of my visit to you – our Rebbe advised me that you can provide me with the answer.”

“What is your question?” asked Reb Zusha.

The visitor repeated what he had asked of the Baal Shem Tov. “You know,” said Reb Zusha, “come to think of it, you raise a good point. But why did the Rebbe send you to me? How would I know? He should have sent you to someone who has experienced suffering…”

The disciple of the Baal Shem Tov, many centuries later, demonstrated the lessons learned by the disciple of Jesus of Nazereth:

I am not saying this because I am in need, for I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances. I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want. I can do all this through him who gives me strength. –Philippians 4:11-13

In all of our circumstances God is there. He is the source of everything both good and bad. We can hardly fail to acknowledge Him, both in our utmost joy and in abject and bitter sorrow. Yet Rabbi Tzvi Freeman records the wisdom of the Rebbe, Rabbi M.M. Schneerson as perhaps the best way to look at how we may bless God no matter what is happening to us as he says in Open Eyes:

After 33 centuries, all that’s needed has been done. The table is set, the feast of Moshiach is being served with the Ancient Wine, the Leviathan and the Wild Ox—and we are sitting at it.

All that’s left is to open our eyes and see.

Regardless of our happiness or pain, let us strive to bless the Lord that we may one day take our places “at the feast with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 8:11).

Good Shabbos.