“For this reason the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who wished to settle accounts with his slaves. When he had begun to settle them, one who owed him ten thousand talents was brought to him. But since he did not have the means to repay, his lord commanded him to be sold, along with his wife and children and all that he had, and repayment to be made. So the slave fell to the ground and prostrated himself before him, saying, ‘Have patience with me and I will repay you everything.’ And the lord of that slave felt compassion and released him and forgave him the debt. But that slave went out and found one of his fellow slaves who owed him a hundred denarii; and he seized him and began to choke him, saying, ‘Pay back what you owe.’ So his fellow slave fell to the ground and began to plead with him, saying, ‘Have patience with me and I will repay you.’ But he was unwilling and went and threw him in prison until he should pay back what was owed. So when his fellow slaves saw what had happened, they were deeply grieved and came and reported to their lord all that had happened. Then summoning him, his lord said to him, ‘You wicked slave, I forgave you all that debt because you pleaded with me. Should you not also have had mercy on your fellow slave, in the same way that I had mercy on you?’ And his lord, moved with anger, handed him over to the torturers until he should repay all that was owed him. My heavenly Father will also do the same to you, if each of you does not forgive his brother from your heart.”

–Matthew 18:23-35 (NASB)

Christian tradition has upheld the high ethical teachings of Jesus concerning forgiveness. While the parable of the Unforgiving Servant is found only in Matthew’s Gospel, its message is stressed in the Lord’s Prayer, which became a vital expression of Christian faith. The prayer for Jesus’ disciples with its dynamic petition, “Forgive us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors,” finds a prominent position in the Didache, which demonstrates that the early Christians emphasized the theme of forgiveness in the life of the church…Could the Lord’s prayer as recorded in the Didache have been influenced by the wording of this parable?

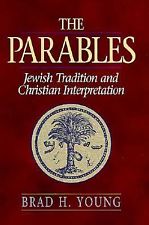

-Brad H. Young

Chapter 6: The Merciful Lord and His Unforgiving Servant

“The Parable in Christian Tradition,” pg 120

The Parables: Jewish Tradition and Christian Interpretation

I’m only a little more than half way through Young’s book but each chapter follows a similar pattern, taking a particular parable of Jesus (Yeshua) and running it past a specific analytical matrix. This isn’t unlike what Roy Blizzard has done in his book Mishnah and the Words of Jesus which I reviewed last spring. Blizzard compared various teachings of Jesus to those of the Rabbinic sages within a generation either side of the (earthly) lifetime of Jesus and determined that Jesus very much taught within the Rabbinic context of the late second Temple era.

Young, chapter by chapter, takes a specific parable of Jesus, shows his readers the traditional Christian interpretation, and then re-examines the parable through the lens of Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries, as well as later Jewish writings. This method also reminded me of a teaching by First Fruits of Zion (FFOZ) founder and president Boaz Michael that he gave a few years back called “Moses in Matthew” which I had the opportunity to listen to (as an audio recording) and review nearly thirteen months ago.

Young, chapter by chapter, takes a specific parable of Jesus, shows his readers the traditional Christian interpretation, and then re-examines the parable through the lens of Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries, as well as later Jewish writings. This method also reminded me of a teaching by First Fruits of Zion (FFOZ) founder and president Boaz Michael that he gave a few years back called “Moses in Matthew” which I had the opportunity to listen to (as an audio recording) and review nearly thirteen months ago.

This method of understanding the words of the Master brings into question traditional Church exegetical concepts such as “the sufficiency of Scripture” and “let Scripture interpret Scripture,” both of which suggest that all you need to understand the Bible in general and Jesus in particular is you and a Bible translated into your native language (which for me is English). While most Evangelical Pastors will also say that a good concordance is helpful and it’s even better to understand the original languages along with something of the context in which the Biblical writers authored their works, they tend to neglect understanding the Judaism in which each Bible writer lived, worked, learned, and taught.

Apprehending Scripture from within an ethnically, religiously, historically, linguistically, culturally, and experientially Jewish framework often yields different interpretative results than the traditions handed down by the Christian Church in its many denominational “flavors”.

Although humor is difficult to define and understand because of cultural barriers, Jesus’ dry wit comes through in this story of one very fortunate servant.

-Young, ibid

I quoted this short sentence to illustrate both the point of “cultural barriers” and how we could miss something so elementary as humor. When we read the Bible, we tend to believe that it is always written in the utmost seriousness and, in many conservative Fundamentalist churches, the literal meaning of the text is always given tremendous weight. But what if the writer is saying something ironic, using Hebrew and Aramaic wordplay, rabbinic idiom? What if the writer is telling a joke?

If we don’t access resources to support our understanding of how Jesus most likely was teaching and how his immediate audience (those listening to him) and extended audience (the originally intended readers of the Gospels and Epistles) were expected to understand what he said, we are left with what we think it all means from a 21st century Christian American point of view.

If we don’t access resources to support our understanding of how Jesus most likely was teaching and how his immediate audience (those listening to him) and extended audience (the originally intended readers of the Gospels and Epistles) were expected to understand what he said, we are left with what we think it all means from a 21st century Christian American point of view.

Please keep in mind that point of view almost never takes ancient Judaism into account let alone immerses itself in said-Judaism as a pool of interpretive wisdom. In other words, we’re probably making a lot of wrong assumptions and coming to many erroneous conclusions.

In the cultural context, the sacred calendar of the Jewish people may provide the setting in life for this parable. The ten-day period between the Jewish New Year and the day of Atonement was designed for seeking forgiveness between individuals. A person was not prepared to seek divine mercy during the great fast on the day of Atonement if he or she had not first sought reconciliation with his or her neighbor. The day of Atonement was the experience of the community as every person participated in the fast. The preparation for this collective experience, however, focused on the necessity to forgive one another on a personal level so as to approach God without a bitter heart. Mercy from above depended upon showing mercy to those below (Compare to Matthew 5:23-24).

-Young, pp 123-4

We can see a corollary in Talmud:

For transgressions that are between a person and God, the Day of Atonement effects atonement, but for the transgressions that are between a person and his or her neighbor, the Day of Atonement effects atonement only if one first has appeased one’s neighbor.

-See m. Yoma 9:9 (Mishnah, ed. Albeck, 247)

quoted by Young, pg 124

We see the scene of the parable being unpackaged right before our eyes in the pages of Young’s chapter to illustrate what we should plainly see Jesus teaching: that the forgiveness of God and atonement for sins is dependent on our forgiveness of others who have sinned against us. If we believe we have been forgiven by God and our sins washed away, and yet fail to forgive those who have sinned against us, will the God of Heaven truly forgive? If we have sinned against another and asked God alone for favor rather than first seeking out the forgiveness of the one we have offended, will God forgive in the stead of the person against whom we have sinned?

Of course, if we have sought forgiveness and been spurned, we can only be held responsible for our own part. We cannot make another person forgive us if it is not in their heart to do so.

If possible, so far as it depends on you, be at peace with all men.

–Romans 12:18 (NASB)

The lack of forgiveness in response to our sincere desire to repent to one against whom we have sinned is on the other’s head as long as we’ve done all we can to make amends and repay them for the wrong we have done.

The lack of forgiveness in response to our sincere desire to repent to one against whom we have sinned is on the other’s head as long as we’ve done all we can to make amends and repay them for the wrong we have done.

There’s another implication in Young’s interpretation of Jesus’ parable based on his invoking the time period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Particularly in Orthodox Judaism, it is believed that a Jew is written into the Book of Life year by year. It is an opportunity to have God hit a sort of “cosmic reset button” for the year to come, but it requires great effort on the part of the individual to make amends for sins committed, both against man and God, to perform good deeds, and give to charity.

This is quite foreign to a Christian’s point of view, particularly if you believe “once saved, always saved.” The moment you confessed Christ as Lord and believed in him, you were saved from your sins and guaranteed a place in Heaven when you die. You need to nothing else, and in fact, it’s impossible for you to do anything else.

That’s the truncated version of the traditional Christian understanding of the Gospel message, anyway.

It is said that there are two resurrections. The first is called the “resurrection of the righteous” and only those who “died in Christ” will be resurrected at the second coming of Jesus. They/we will all be raised into the air to meet him, and according to traditional Evangelical doctrine, the Church will then be raptured into Heaven to wait out the full fury of the Tribulation on Earth. Then, when all the bad stuff is over, Jesus leads the Church back down to Earth to establish his Kingdom where the Church will rule with him over a New Earth.

Or so it goes as far as many Christian churches are concerned.

The second resurrection is called the “great white throne” judgment where everyone who has died is resurrected and judged by God, with the righteous living in bliss for all eternity, and the wicked being cast into the lake of fire to suffer torment for all eternity.

But how does that judgment work? If we just believe in Jesus will we be saved automatically? Will we be given a free pass into Heaven? What about being forgiven by God as we’ve forgiven others?

What if the final judgment is like the ultimate Yom Kippur service? Have you ever been to a Yom Kippur service? It’s the single most solemn day on the Jewish religious calendar, full of tears, fasting, remorse, repentance, trembling, and fear.

It is a terrifying thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

–Hebrews 10:31 (NASB)

The unmerciful servant does not forgive like his master. The lord of the servants, however, is not only merciful but just. The one who would not forgive will not receive a reprieve. His fellow servants recognize the injustice and report the actions of their unmerciful coworker to the lord. He is enraged.

-Young, pg 128

Belief in Jesus is hardly sufficient by this Biblical standard. What you think and feel is only part of the equation. What you do out of your faith is what really matters.

Belief in Jesus is hardly sufficient by this Biblical standard. What you think and feel is only part of the equation. What you do out of your faith is what really matters.

They were passing through in the morning, and they saw that the fig tree had withered from its roots. Petros remembered and said to him, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree that you cursed is withered!”

Yeshua answered and said to them, “Let the faith of God be in you. For amen, I say to you, anyone who says to this mountain, ‘Be lifted up and moved into the middle of the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart, but rather believes that what he says will be done, so it will be for him as he has said. Therefore I say to you, all that you ask in your prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be so for you. And when you stand to pray, pardon everyone for what is in your heart against them, so that your Father who is in heaven will also forgive your transgressions. But as for you, if you do not pardon, neither will your Father who is in heaven forgive your transgression.

–Mark 11:20-26 (DHE Gospels)

If this is so as we are judged by God day-by-day, how much more so is it true when we come before the Throne of God at final judgment and the great day of atonement?

Yet, for all its importance, the ritual of the synagogue is but a means to an end. In Judaism, behavior takes priority over belief. Faith without deeds will not change the world.

-Ismar Schorsch

“The Root of Holiness,” pg 553, July 12, 2003

Commentary on Torah Portion Balak

Canon Without Closure: Torah Commentaries

What use is it, my brethren, if someone says he has faith but he has no works? Can that faith save him? If a brother or sister is without clothing and in need of daily food, and one of you says to them, “Go in peace, be warmed and be filled,” and yet you do not give them what is necessary for their body, what use is that? Even so faith, if it has no works, is dead, being by itself.

But someone may well say, “You have faith and I have works; show me your faith without the works, and I will show you my faith by my works.” You believe that God is one. You do well; the demons also believe, and shudder. But are you willing to recognize, you foolish fellow, that faith without works is useless?

–James 2:14-20 (NASB)

It is doubtful that Schorsch meant to parallel the teachings of James the Just, brother of the Master, but this may reflect the fact that principles from ancient Judaism (for the teachings of Jesus and James are wholly Jewish), some at least, have survived the passage of time and endure in modern Jewish practice. As Christians, for anything we find good and gracious in our theology and doctrine, we must give thanks not only to God but to Judaism for its origins.

However, if we accept that, we must also accept that a Jewish understanding of the teachings of Jesus place a much greater burden on the shoulders of a Christian than many Pastors have led us to believe. Fortunately, I currently attend a church where this burden is taught and where sincerity of repentance and love and forgiveness of our neighbor and brother is held in great value.

Also fortunately, the God of Justice is also the God of Mercy:

Then the Lord passed by in front of him and proclaimed, “The Lord, the Lord God, compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in lovingkindness and truth; who keeps lovingkindness for thousands, who forgives iniquity, transgression and sin; yet He will by no means leave the guilty unpunished, visiting the iniquity of fathers on the children and on the grandchildren to the third and fourth generations.”

–Exodus 34:6-7 (NASB)

He remembered His covenant for them and relented in accordance with His abundant kindness.

–Psalm 106:45 (Stone Editon Tanakh)

…but if that nation repents of its evil deed of which I had spoken, then I relent of the evil [decree] that I had planned to carry out against it. Or, one moment I may speak of concerning a nation or kingdom, to build and establish [it], but if they do what is wrong in My eyes, not heeding My voice, then I relent of the goodness that I had said to bestow upon it.

–Jeremiah 18:8-9 (Stone Edition Tanakh)

God is eager to do good to all those who call upon His Name in sincere repentance and who do what is right, but to those who call upon Him yet continue to do what is wrong, there is no mercy, but instead, righteous judgment.

As Christians, we cannot afford to take our (so-called) salvation for granted, for who is to say that God won’t keep His word as He has given it and as Jesus has taught it? Who is to say that our forgiveness (or lack thereof) of others won’t be the model by which God will (or won’t) forgive us?

Young writes this by way of conclusion to his commentary on this parable:

The parable shows the deep roots of Jesus’ teachings in ancient Judaism. Jesus’ Jewish theology of God saturates the drama of the story as the action moves from scene to scene. The listener is caught up into the plot of the mini-play and participates in the trial, triumph, and tribulation of the servant. What happens when it is impossible to pay one’s creditor?

…The cultural and religious background is based on the teachings concerning the great day of fasting in Israel’s sacred calendar, which each person seeks forgiveness from God. The creation of humanity, in the very image of God, demands full accountability, which means that one must be merciful in the same way that God shows mercy. The images created by the parable lead the listener to join the actors on the stage. Each individual must ask God for forgiveness of a colossal debt. To what extent, however, do I extend mercy to others who have wronged me?

-Young, pg 129

The answer would seem obvious and Young addresses it again in the following chapter, “Chapter 7: The Father of Two Lost Sons,” his commentary on the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32):

Jesus makes this a major theme in the prayer he taught his disciples: “Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” On the day of Atonement, the Mishnah instructs the people to make things right one with the other before seeking forgiveness from God (m. Yoma 8:9). Thus the idea of human forgiveness is strong in Jewish theology.

-Young, pg 134

These parables are not cute little sayings of Jesus to teach us some interesting moral lesson. They are cautionary tales, warnings to the disciples, including us, that what we do and why we do it really does matter, and, looking back to the words of the prophet Jeremiah, what we have been given can be taken away at any time should we prove to be faithless and insincere, both to God and to our fellow human beings (also see Matthew 25:14-30).

While I suppose it’s not absolutely necessary to study the Bible from a culturally and religiously Jewish perspective and still live a good and upright Christian life, we see here, as I’ve pointed out many times before, that without a little extra “help” through an understanding in the wider body of Jewish religious literature, we can often miss the point, giving more power to Christian traditional interpretations than in what Jesus said in context. The Church has been taught to avoid that context because it has been taught that (if not the Jewish people) Judaism has been sitting on the shelf long past its expiration date. The Law is dead. The Jewish people just don’t know it yet.

While I suppose it’s not absolutely necessary to study the Bible from a culturally and religiously Jewish perspective and still live a good and upright Christian life, we see here, as I’ve pointed out many times before, that without a little extra “help” through an understanding in the wider body of Jewish religious literature, we can often miss the point, giving more power to Christian traditional interpretations than in what Jesus said in context. The Church has been taught to avoid that context because it has been taught that (if not the Jewish people) Judaism has been sitting on the shelf long past its expiration date. The Law is dead. The Jewish people just don’t know it yet.

Except that’s not the case and can’t be. Without a Jewish understanding of the teachings of Jesus filtered through an ancient and arguably modern practice of Judaism, the words of Jesus are just words on a page, devoid of some or much of their actual meaning. And without that meaning, the depth of our faith and how we actually live it out, including forgiveness, is just as absent of meaning. It may be good and even sufficient, but it could be so much more.

To what then may we compare (entry into) the Kingdom of Heaven?

I hereby forgive anyone who has angered or provoked me or sinned against me, physically or financially or by failing to give me due respect, or in any other matter relating to me, involuntarily or willingly, inadvertently or deliberately, whether in word or deed: let no one incur punishment because of me.

-Bedtime Shema from the Siddur