Before discussing how the Baal Shem Tov revolutionized the Jewish view on joy, it must be mentioned that happiness was never foreign to Judaism. As King David declared: “Serve G‑d with joy!” Indeed, the Talmud states that “One should not stand up to pray while dejected…but only while still rejoicing in the performance of a mitzvah.”

The concept of simcha shel mitzvah, the “joy of a mitzvah,” has always been part and parcel of Jewish teachings. After all, can there be a greater privilege than serving the King of kings? As such, mitzvot must be executed with joy.

-Baruch S. Davidson and Naftali Silberberg

“Perpetual Joy:

The Baal Shem Tov’s Revolutionary Approach to Joy”

Chabad.org

I’ve been thinking about my role in church lately, as well as the Biblical and historic perspective ancient (and modern) Judaism had (has) regarding “doing” as opposed to “believing.”

It’s not that the Church doesn’t believe in doing good works, but the incredible phobia some Christians have against even appearing as if there’s a connection between salvation and what we do, makes the Church hold their good deeds pretty much at arm’s length, including repentance. Worse, the Church tends to judge all forms of Judaism but particularly Orthodox Judaism, as a “dead works based religion” with no foundation in faith or spirituality.

I suppose there could be some truth to the accusation, particularly if performance takes on a life of its own to the degree that there is no apprehension of God. What’s the point if observance is just a list of arduous duties that impinge on a person’s relationship with God rather than enhancing it? I’ve heard stories of Jews who feel virtually bound and gagged by the Torah commandments, which is how most Christians see “the Law”. Of course, as we see from the quote above, there’s a flip side to a traditional Jewish life.

Every mitzvah should be performed with joy. One aspect of “mitzvah joy” is to do the good deed with all your energy and ability.

For example: Rather than offer a needy person a morsel of food, serve him a hearty meal!

-Rabbi Zelig Pliskin

Do Mitzvahs with Joy

A person who feels joy when performing mitzvahs will forget all his suffering and misfortunes. In comparison to becoming closer to the Almighty, of what import is pettiness and trivialities?

A person who experiences joy in doing good deeds will feel greater joy than a person who finds a large sum of money. Why should a person expend his efforts trying to find happiness in areas where the basis is transient and ultimately meaningless, when he has a far better alternative?

-R. Pliskin

Joy in Mitzvahs Greater than this World

Granted, Rabbi Pliskin’s viewpoint may not represent all Orthodox Jews everywhere, but I consider his perspective, as well as the Baal Shem Tov’s, to be the ideal that Jewish people shoot for or should shoot for. I’ve repeatedly heard people at the church I attend express joyfully how they are so glad we are no longer “under the Law” (even though Gentiles were never “under the Law”) and are free in Christ, as if performing even the slightest commandment from the Bible (such as loving God with all your resources or not considering things like bacon, shrimp, or catfish as food) in obedience to God would be an incredibly difficult thing.

Tell me Christians, if God asked you to do something like, oh, I don’t know, help someone who was beaten by robbers and left for dead, a person who you may not even like, getting them medical attention, and paying for it all out of your own pocket (Luke 10:25-37), would you tell God “no” because that would be “dead works” (and I’ve written about the true meaning of dead works before)?

Hopefully, you’d respond to my question by saying of course you’d obey God’s commandment to love your neighbor as yourself (Leviticus 19:18, Matthew 22:39, Mark 12:31).

But it’s a commandment and one rooted in the Law (Torah). Of course they’re all rooted in the Torah, the instructions, the conditions God gave the Israelites at Sinai when He made His covenant with them. Granted, how the Torah is applied to grafted in Gentile disciples of the Master (Jesus) is different than how Torah was and is applied to Jewish people (including Jewish disciples of the Master), but we are still obligated to obey God in all that He desires in our lives.

How can you even question that?

The key to obeying God is joy.

Now this I say, he who sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and he who sows bountifully will also reap bountifully. Each one must do just as he has purposed in his heart, not grudgingly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.

–2 Corinthians 9:6-7 (NASB)

Paul’s statement wouldn’t be out-of-place in any Jewish context, ancient or modern, and I think even the Baal Shem Tov would have agreed with him.

But this is a part of scripture that Pastors often preach from when they’re asking for an increase in tithes from their congregations, especially if the church elders have approved of a special project, an expansion of the church building, or if the church’s income is falling behind what they projected in their annual budget.

But this is a part of scripture that Pastors often preach from when they’re asking for an increase in tithes from their congregations, especially if the church elders have approved of a special project, an expansion of the church building, or if the church’s income is falling behind what they projected in their annual budget.

I agree that anyone who consumes a church’s resources should provide for the church’s income but how many people give tithes or increase their giving out of a sense of obligation, guilt, or even sometimes, intimidation? How many Christians give to their local church and other worthy causes out of sheer joy?

I can’t answer that last question, but hopefully, quite a lot. But my knowledge of human nature tells me that a Pastor who preaches that their congregation should give more when they tithe because of the sense of joy they’ll experience and that tithing will bring them closer to God might not see a resulting increase in congregational giving.

But that’s exactly the approach that should work if Christians obeyed all that God asks of them/us with joy.

Rabbi Joseph Albo, the 15th century author of the classic work Sefer Haikarim, writes: “Joy grants completion to a mitzvah, only through it does the mitzvah achieve its intended objective.” Similarly, Rabbi Elazar Azkari, 16th century Safedian scholar and author of the work Charedim, writes: “The main reward for a mitzvah is for the great joy in it.” “The reward is commensurate to the joy [with which the mitzvah is performed].”

Indeed, the 16th century Kabbalist, Rabbi Isaac Luria, known as the Arizal, once said that all that he achieved – the fact that the gates of wisdom and divine inspiration were opened for him – was a reward for his observance of mitzvot with tremendous, limitless joy!

-Davidson and Silberberg

But what’s the connection between obedience and joy? We don’t obey the traffic laws because it will increase our joy, we obey laws because we have to and we’ll be punished (by getting a traffic ticket, for instance) if we disobey (and are caught).

One of the most common misconceptions deals with the word “sacrifice.”

We often think of sacrifices in the Temple in terms of buying off an angry deity with lots of blood and guts.

Alas, these pagan ideas show how much our thinking has been influenced by other cultures. God is not lacking anything and does not need our sacrifices — animal or any other kind.The offerings that were brought in the Temple, like all the commandments, were not done for God. They were done for us.

In fact, the Hebrew word for sacrifice, korban, comes from the root korav meaning to “come close,” specifically, to come close to God. The offering was meant to bring someone who was far near once again.

To understand something of the intense, elevating experience that bringing an offering must have been, let’s take a look at a typical offering: the peace offering.

-Rabbi Shmuel Silinsky

Understanding the Sacrifices

Most Christians and even a lot of Jews, think of the ancient Temple sacrifices as bloody, horrible, messes that they’re glad don’t happen anymore. Many Christians and even many Jews don’t believe a third Temple will ever be built and are relieved that God never again will require anyone to offer animal sacrifices in Jerusalem. But if you click the link I provided and read all of Rabbi Silinsky’s commentary, you’ll see they are missing the point.

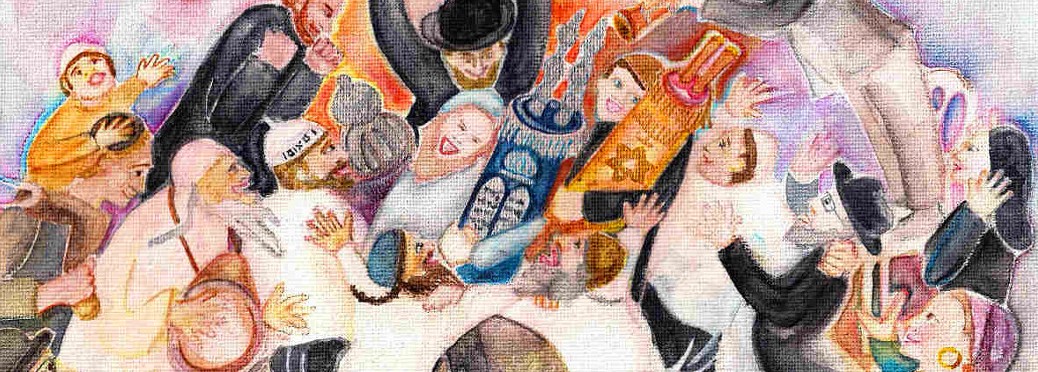

We Christians (most of us) also miss the point about joyfully performing the mitzvot and even actively looking for ways to perform a mitzvah. Could you imagine a Christian waking up one morning and the first thing that popped into his or her head was, “I can’t wait to find ways to serve my Lord today!”

We Christians (most of us) also miss the point about joyfully performing the mitzvot and even actively looking for ways to perform a mitzvah. Could you imagine a Christian waking up one morning and the first thing that popped into his or her head was, “I can’t wait to find ways to serve my Lord today!”

OK, there probably are some Christians like that out there, but I suspect they aren’t all that common. I know that the first thing I think of in the morning is my getting my first cup of coffee.

Well, that’s not quite true.

I gratefully thank you living and existing King for returning my soul to me with compassion. Abundant is your faithfulness.

That’s the first blessing an observant Jew will recite upon awaking in the morning. I memorized it (in English) and when I first wake up, even before throwing the covers off and getting out of bed, this is what I say.

Since coming to the conclusion a few years back, that Torah observance looks differently when performed by a Gentile than by a Jew (it’s a complicated topic), I severely scaled back on any behaviors that could appear “Jewish” (not that my observance was really, authentically Jewish). I didn’t do so because I think Torah observance is bad or that the mitzvot are a burden, but out of respect and honor to those special chosen people of God who received the Torah of Moses at Sinai, the Jewish people. Of course, being married to a Jewish wife was quite a motivator as well, since in no way do I desire to diminish or demean what it is for her to be a Jew.

But even if the rest of my day turns to doggie-doo, the very first thought I have is of God and being grateful to Him. Am I always truly grateful each morning? That is, do I feel a sensation, an emotional experience of gratitude? No, not always, and probably not most of the time. My brain is still foggy moments after I wake up. On the other hand, I do realize that I’m alive and that it’s because of God.

The last thing I think about before turning off the light and going to sleep is also of God.

A song of ascents. Praiseworthy is each person who fears Hashem, who walks in His paths. When you eat the labor of your hands, you are praiseworthy and it is well with you. Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine in the inner chambers of your home, your children like olive shoots surrounding your table. Behold! For so shall be blessed the man who fears God. May Hashem bless you from Zion, and may you gaze upon the goodness of Jerusalem all the days of your life. And may you see children born to your children, peace upon Israel!

Tremble and sin not. Reflect in your hearts while on your beds, and be utterly silent. Selah.

Master of the universe, Who reigned before any form was created, At the time when His will brought all into being — then as ‘King’ was His Name proclaimed. After all has ceased to be, He, the Awesome one, will reign alone. It is He Who was, He Who is, and He Who shall remain, in splendor. He is One — there is no second to compare to Him, to declare as His equal. Without beginning, without conclusion — He is the power and dominion. He is my God, my living Redeemer, Rock of my pain in time of distress. He is my banner, and refuge for me, the portion in my cup on the day I call. Into His hand I shall entrust my spirit when I go to sleep — and I shall awaken! With my spirit shall my body remain, Hashem is with me, I shall not fear.

This is only part of the full Bedtime Shema. I recite only this portion because, as a Gentile, I want my observance to not precisely mirror the performance of the mitzvah by a Jew. I must also admit that by this time of night, my brain isn’t working so well, and I have a difficult time concentrating on anything, including God, as I should, so a shorter form of this blessing seems more suitable. And yet I take comfort that as I surrender my consciousness, I’m also surrendering to God.

This is only part of the full Bedtime Shema. I recite only this portion because, as a Gentile, I want my observance to not precisely mirror the performance of the mitzvah by a Jew. I must also admit that by this time of night, my brain isn’t working so well, and I have a difficult time concentrating on anything, including God, as I should, so a shorter form of this blessing seems more suitable. And yet I take comfort that as I surrender my consciousness, I’m also surrendering to God.

From a Jewish point of view, between the Modeh Ani and the Bedtime Shema blessings, is a world of opportunity to serve God by performing as many of the mitzvot as can be encountered in a single day and as Hashem offers them in their lives.

Lebisch: Rabbi! May I ask you a question?

Rabbi: Certainly, Lebisch!

Lebisch: Is there a proper blessing… for the Tsar?

Rabbi: A blessing for the Tsar? Of course! May God bless and keep the Tsar… far away from us!

–Fiddler on the Roof (1971)

I didn’t remember that dialog correctly. In my memory, I had the Rabbi respond, “My son, there is a blessing for everything,” and then he gave his humorous blessing about the Tzar.

But particularly in Orthodox Judaism, there is a blessing for everything. Just look at the table of contents of a siddur (Jewish prayer book). There are as many variations of the siddurim (plural for siddur) in Judaism as there are hymnals in Christianity. I just found an Ashkenaz online siddur at Chai Lifeline so you can have a look at the different blessings right now. And in a pinch, if a Jew did not have his or her siddur present but did have a device that could hit the Internet, they could still daven.

In the Church, we can choose to believe that all religious Jews are bound to a sterile, dead, spiritless set of archaic and meaningless laws that are designed to enslave them and that come straight from Satan and the pit of Hell. But that’s not the truth. It wasn’t true in the days when Jesus walked in Judea, it wasn’t true when Paul brought scores of Gentiles to faith in the Jewish Messiah, and it isn’t true today.

I can’t speak for every observant Jewish person and judge the intent of their hearts when performing the mitzvot anymore than I can speak for every Christian and judge their hearts when going to church, praying, visiting sick people in the hospital, and doing all those things they believe make up a good Christian life. Maybe some Jews pass up a BLT sandwich out of obligation rather than in joyful obedience to God, and maybe some Christians visit a sick relative in the hospital out of obligation rather than joyful obedience to Jesus.

But that doesn’t mean Judaism or Christianity are bad or worthless just because not all Jews or Christians don’t live up to the ideals set before them…before us by God. And when we do find a Jew or Christian who does live up to that ideal, a true tzaddik or saint, then it’s an amazing inspiration for the rest of us to try harder and do better at being the sort of person God designed us to be.

The animal has actually become a korban, a way of helping its owner to come closer to God. Eating this meal is now a very spiritual experience. It is being raised from the level of animal to that of human, by actually becoming a part of the consumer and by being the vehicle for the entire process.

One can easily see how a meal like this can be a focal point of holiday observance.

-R. Silinsky

Until Messiah comes and rebuilds the Temple, no animal sacrifices will be offered in Jerusalem. For the past nearly two-thousand years, Jews have considered prayer, Torah study, and performance of the mitzvot, as many as can be observed without a Temple, without a priesthood, and without a Sanhedrin, especially outside of Israel, as the substitutes for the sacrifices.

Christians believe that the crucifixion of Jesus substituted for all of the sacrifices rendering them obsolete and meaningless, right along with the rest of the Torah and observant Judaism.

The Church cannot imagine that anyone, Jew or Christian, can actually draw closer to God through any sort of action since behavioral obedience to God in any fashion is considered “dead works.”

The Church cannot imagine that anyone, Jew or Christian, can actually draw closer to God through any sort of action since behavioral obedience to God in any fashion is considered “dead works.”

But how can you ignore a life driven by the desire to serve God by serving other human beings? How can you deny a life motivated each day by looking forward to serving God in as many ways as you can, and even going out of your way to find opportunities to do good just for the sake of doing good?

I know calling joy a reward makes performance of the mitzvot seem self-serving rather than God-serving, but the joy isn’t in the doing, but the drawing nearer to God. Sure, we can pray, “God, please come nearer to me,” but why not demonstrate your desire by actually doing what God wants you to do? The “sacrifice of praise?” Sure. But we can praise God not just with our lips, but with our hearts, and our hands, and our feet, and our strength, and our compassion.

This people honors me with their lips but their heart is far away from me.

–Matthew 15:8 (NASB) quoting Isaiah 29:13

Anyone, Jew or Christian, can lifelessly go through the motions of obedience to God. That doesn’t invalidate either observant Judaism or Christianity. That doesn’t invalidate the intent of God for our lives. You can’t point to a Jew and say their less than stellar performance of the mitzvot, or even their complaints about said-observance, are proof that Judaism, including Messianic Judaism, is not God’s desired response of a Jewish life, anymore than you could invalidate Christianity based on the life of a lackluster Christian (and plenty of atheists try to invalidate Christianity by judging such Christians).

Praise God with your lips, just make sure your praise is backed up with your heart’s desire and the joy of serving your Master and His creations, all of humankind. Then you will draw nearer to God through His teachings.

The Torah of Hashem is perfect, restoring the soul; the testimony of Hashem is trustworthy, making the simple one wise; the orders of Hashem are upright, gladdening the heart; the command of Hashem is clear, enlightening the eyes; the fear of Hashem is pure, enduring forever; the judgments of Hashem are true, altogether righteous. They are more desirable than gold, than even much fine gold; and sweeter than honey, and drippings from the combs. Also, when Your servant is scrupulous in them, in observing them there is great reward. Who can discern mistakes? Cleanse me from unperceived faults. Also from intentional sins, restrain Your servant; let them not rule over me, then I shall be perfect; and I will be cleansed of great transgression. May the expressions of my mouth and the thoughts of my heart find favor before You, Hashem, my Rock and my Redeemer.

–Psalm 19:8-15 (Stone Edition Tanakh)

For more, see Why the Torah is the Tree of Life.