If a man will have a wayward son, who does not hearken to the voice of his father and the voice of his mother, and they discipline him, but he does not hearken to them; then his father and mother shall grasp him and take him out to the elders of his city and the gates of his place. They shall say to the elders of his city, “This son of ours is wayward and rebellious; he does not hearken to our voice; he is a glutton and a drunkard.” All the men of his city shall pelt him with stones and he shall die; and you shall remove the evil from your midst; and all Israel shall hear and they shall fear. –Deuteronomy 21:18-21 (The Stone Edition Chumash)

If a man will have a wayward son, who does not hearken to the voice of his father and the voice of his mother, and they discipline him, but he does not hearken to them; then his father and mother shall grasp him and take him out to the elders of his city and the gates of his place. They shall say to the elders of his city, “This son of ours is wayward and rebellious; he does not hearken to our voice; he is a glutton and a drunkard.” All the men of his city shall pelt him with stones and he shall die; and you shall remove the evil from your midst; and all Israel shall hear and they shall fear. –Deuteronomy 21:18-21 (The Stone Edition Chumash)

This commandment, from yesterday’s Torah Reading Ki Tetzei, is very difficult for us to understand. It’s one of the examples that Christians traditionally point to in explaining why God has removed the law and replaced it with grace. It’s one of the commandments the secular world uses to illustrate the “evil” religion represents and how much better humanistic and “progressive” atheism is in terms of compassion for others, including children and “wayward teens”.

This is also an example of how you can’t just read the Bible, any part of it, without employing some modifying information to help understand what is being taught. After all, even if your son is a total rebel, drunken, disobedient, even a criminal, what mother and father could simply hand him over to the court and, without a trial or any due process, watch him be stoned to death at the gates of their city?

But then, if the Torah as we have the document in our hands today doesn’t present the whole story, and if it didn’t fully explain commandments like this one when they were given in the day of Moses, how can we possibly understand the Bible? Let’s take another example.

He returned and began to teach by the seashore, and a great crowd of people was assembled to him. He went down and sat in a boat in the sea, and all the people stood on the seaside on dry land. He taught them many things with parables, and he said to them as he taught them:

Listen closely: The sower went out to sow seed. As he sowed, some of the seed fell by the road, and the birds of heaven came and ate it. There was some that fell on a rocky place where there was not much soil, and it sprouted quickly because it did not have deep soil. When the sun shone, it was scorched and dried up because it had no root. There was some that fell among thorns, and the thorns came up and crowded it out, and it did not bear fruit. There was some that fell on the good soil, and it bore fruit, coming up and growing. One made thirty times, another sixty, and another a hundred. –Mark 4:1-8 (DHE Gospels)

This is the entire text of the parable that Jesus taught to those listening to him at the lake. In verse 9, we read Jesus saying, “Whoever has ears to hear, let him hear.” If Mark had ended his narrative there and we had no other way to interpret the words of the Master, we might be just as puzzled as Christ’s audience. Even the Master’s closest inner circle of disciples had no idea what he was saying. Sure, you know what Jesus meant when he told the parable, but only because you’ve read his explanation as he related it to his most intimate of disciples:

When he was alone, the men that were with him approached with the twelve and they asked him about the parable. And he said to them:

To you it is given to know the secret of the kingdom of God, but to those outside, everything is in parables, so that they may look closely, but they will not know. They will listen well, but they will not understand, or else they may repent and be forgiven for their sins.

And he said to them:

Do you not know this parable? How will you understand any of the parables? The sower sows the word. Beside the road, these are those in whom the word is sown, but when they hear it, the satan immediately comes and picks up the word that is planted in their heart. Likewise, the ones sown on the rocky places are those who hear the word and they quickly receive it joyfully. But they have no root in them, and they only stand for an hour. After that, when trouble and persecution come on account of the word, they quickly stumble. And these are those sown among the thorns: They are those who hear the word, but the worries of this age and the guile of wealth and other cravings come and crowd out the word, and it does not have fruit. But these are those sown on the good soil: They are those who hear the word and receive it, and they produce fruit. One produced thirty times, another sixty, and another a hundred. –Mark 4:10-20 (DHE Gospels)

I want to emphasize my point here so I’ll quote verse 10 again: “the Twelve and the others around him asked him about the parables.” Even those who walked and talked with Jesus daily had no idea what he meant when he taught in parables. Only those closest to him were able to ask what he meant and hear his more straightforward explanation. We have the parable and the explanation together only because Mark and the other Gospel writers documented them together decades after these lessons were originally spoken. It would be many centuries before everything was put together as one “New Testament” and centuries more before the Bible was mass-produced and accessible to anyone who wanted to read it (Gutenberg didn’t invent the printing press until around 1440). We take reading the Bible as a unified document for granted today, but in times past, information like parables and their explanations weren’t always available in one book or scroll.

Now let’s get back to the example of the wayward son and his rather ghastly death sentence. If we, like the audience of Jesus, can’t get the full explanation from one place, where else can we go?

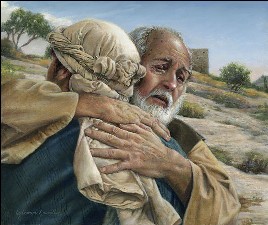

The Torah tells us that the Ben Sorer U’Moreh [Wayward and Rebellious Son] is brought to Beis Din [Jewish Court]. If the evidence is upheld, he is put to death, based on the principle “better he should die innocent now, than have to be executed as a guilty party somewhere down the road.”

The rules and circumstances for a Ben Sorer U’Moreh are so complex, specific and narrow that the Talmud in the eighth chapter of Sanhedrin says that there has never been and will never be a Ben Sorer U’Moreh. So then why, in fact, was the entire section written? The Talmud answers that the section was written in order that we might “expound it and receive reward”. In other words, this section was written for the sake of the lessons inherent in it.

The lessons that the Torah wants us to derive from this section are lessons about raising children. The Torah wants to teach us how we should and should not raise a child. It is likely that some grievous mistakes were made in the raising of the Wayward and Rebellious son. The Torah is providing us with clues of what to do and what not to do when raising our sons and daughters.

-Rabbi Yissocher Frand

“Rabbi Frand on Parshas Ki Seitzei”

Torah.org

This may make the Torah seem even more difficult to comprehend. Why would there be a commandment documented by the hand of Moses for the Children of Israel that they were never expected to obey?” Rabbi Frand tells us the commandment had a much deeper intent regarding parenting but where was this intent to be discovered?

He references the Talmud and particularly tractate Sanhedrin 8, but the Talmud didn’t exist in the time of Moses and wouldn’t be recorded in any written form until after the time of Jesus.

But is that exactly true?

According to classic Jewish thought, when Moses was on Sinai with God for forty days and forty nights (Exodus 24:18), in addition to imparting the instructions for building the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and its various elements, God also gave Moses the Oral Law or the means by which to interpret the directives listed in the written document, such as the aforementioned commandment regarding wayward sons. However, no list of commandments, written or oral, could possibly cover all contingencies and circumstances as they would arise in the following years and centuries, so God also commanded that a group of Judges be assembled to hear the various cases and complaints as they arose (Numbers 11:24-30). Authority was given to this system of Judges, originally the Sanhedrin but in modern times, the rabbinic Beit Din, to make rulings and judgments regarding the practical application of the written and oral Torah we have with us today.

According to classic Jewish thought, when Moses was on Sinai with God for forty days and forty nights (Exodus 24:18), in addition to imparting the instructions for building the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and its various elements, God also gave Moses the Oral Law or the means by which to interpret the directives listed in the written document, such as the aforementioned commandment regarding wayward sons. However, no list of commandments, written or oral, could possibly cover all contingencies and circumstances as they would arise in the following years and centuries, so God also commanded that a group of Judges be assembled to hear the various cases and complaints as they arose (Numbers 11:24-30). Authority was given to this system of Judges, originally the Sanhedrin but in modern times, the rabbinic Beit Din, to make rulings and judgments regarding the practical application of the written and oral Torah we have with us today.

So in the case of the wayward son, for an ancient Israelite, it wasn’t enough to know the written Torah on how best to deal with the situation. You had to learn and understand its intent via the Oral Law given to Moses at Sinai and interpreted by the ancient Israeli judicial system which also was established by God. Add to this that, as you grew up and were taught the elements of Torah by your parents, teachers, and priests, you would learn that the commandment of wayward children was meant not as a harsh punishment to use against your son should he become a drunken thug, but a lesson in how to parent your children so that they would “hearken” to your voice.

All that is fine and well for the Israelites, but you’re probably asking yourself what all this has to do with Jesus and his parables. What if I were to tell you that Jesus did the same thing: took the Torah and interpreted it? Christians believe he did so, but only in the very limited scope of doing away with the Torah, but I believe that, like Moses, like the Sanhedrin, like the lesser courts there were appointed in the various towns in Israel, and like the individual judges, Jesus also gave oral rulings, laws, and interpretations by the authority given to him by God the Father, the great Ayn Sof, the infinite, unknowable, ultimate, and unique One God.

Now look at this. We have a written Bible, for Jews, the Tanakh, what Christians call the Old Testament. It isn’t sufficient as a guide to provide a means by which Jews can apply the will of God in every possible situation they may encounter in their lives (and by inference, it means Christians may not have all the information we need just by reading the Bible). There are many questions Jews encounter as to how a commandment may or may not fit something that happens to them, such as a son coming home late and drunk. In fact, since situations and interpretations change across the scope of time, the Torah couldn’t possibly tell a 21st century Jewish parent how to deal with this situation in a way that would also meet the needs of a 12th century Jewish parent under similar circumstances. Both the Talmudic rulings and probably the advice of a Rabbi or a Beit Din might be needed.

Jesus did the same thing in the New Testament. The most famous example of him doing so is in the “Sermon on the Mount” (see Matthew 5) but keep in mind, Jesus wasn’t undoing the Torah commandments or giving a radical and “unJewish” meaning to them. If he had done that, he would have completely lost his Jewish audience including all of his closest disciples. The reason anyone in ancient Roman Judea listened to Jesus and followed him; the reason even the Pharisees could not discredit anything he taught, was because everything he taught and interpreted was completely consistent with the Torah of Moses and the intent of God at Sinai.

There’s no way that we can simply toss the Oral tradition, the Talmud, and the rabbinic rulings out the window and proceed as if the Bible were a completely self-sufficient document. The Bible is the firm foundation of the Word of God and the Rock on which we all stand. But it is not like a latest best-selling novel that we can read and digest all by itself without studying and relying on authoritative interpretations. Jesus is the living expression of that Rock (“the Word became flesh” –John 1:14). However, Jesus himself must have followed the halakhah or the traditional rulings of Torah observance as understood during the Second Temple period (if he didn’t, all of his followers, including Peter, would have walked away from him, branding him a heretic). Those places where we see him apparently disregarding halakhah, are those points where his authority is giving a better ruling; one more consistent with the original intent of God at Sinai.

Just as Moses, the Sanhedrin, the lesser courts, and the judges and priests of Israel were given authority on earth to interpret Torah and to make rulings and judgments for the people, Jesus was given that authority and more as the Son of God. If we understand Mark 12:28-44 correctly, none of his rulings, judgments, and interpretations contradicted the Torah in any way, although as I mentioned, some of his rulings weren’t entirely consistent with the understanding of the Pharisees and Sadducees. In Jesus, we have a living example of how there can be a written Torah and a set of oral interpretations. This supports the ancient and modern Jewish tradition of having a written Torah, an oral interpretation, as well as later rabbinic rulings which were recorded in the Talmud, and a rabbinic court to interpret Torah and Talmud in individual cases.

Given everything I’ve just said, I’m not supporting that Christians suddenly start trying to live their lives by Jewish standards. Most of what is written in the Torah and Talmud applies only to Jews, but if you’ve been reading this blog for any length of time, you know that I believe Christians can learn much about God, the teachings of Jesus, and the meaning of our lives as disciples of the Master by studying the Jewish texts. If Jesus, in a sense, taught like Moses, like a Judge, like a Priest, and like a Rabbi, then only by learning about and trying to understand the complete system of Jewish teachings and judgments can we even begin to understand the Savior and Messiah we follow and adore.

Like the ancient Israelite and the commandment of the wayward son, we don’t have all the information we need just by reading a few paragraphs in the Bible. Like the inner disciples of Jesus, we don’t understand the parables of the Master given to the masses without his interpretation of them. As modern Christians, we can’t always know the underlying meaning of the teachings of Christ (even though we currently have a record of his parables and their explanations) without digging a little deeper into how Jesus taught like a Maggid.

Like the ancient Israelite and the commandment of the wayward son, we don’t have all the information we need just by reading a few paragraphs in the Bible. Like the inner disciples of Jesus, we don’t understand the parables of the Master given to the masses without his interpretation of them. As modern Christians, we can’t always know the underlying meaning of the teachings of Christ (even though we currently have a record of his parables and their explanations) without digging a little deeper into how Jesus taught like a Maggid.

Christian, I’m not saying that we must take on board the full yoke of Torah including Talmud and halakhah. Far from it. However, I am saying that while it is not required of us, we can still learn a great deal about Jesus by the study of Judaism, for it is from Judaism that our faith has emerged and it is within Judaism that the heart of the Messiah beats for his people, both those who are the natural branches and those of us who have been grafted in (Romans 11).

As believers, we have no right to judge the Jewish people for following the halakhah, from studying Talmud, from living by the rulings of the sages, and from obedience to the Torah of Moses as understood and interpreted by oral tradition and rabbinic judgments. These rules are not binding on us, but the Jewish people were given a more comprehensive yoke than what has been asked of the Gentile disciples (Acts 15). Yet, as implied by James and the Jerusalem Council, there is still value in learning the Torah among the Gentile disciples because it is that Torah, those Judges, those Prophets, those Disciples of the God of Israel that are the core of Christ’s message and the foundation of who we are as believers in Jesus.

You have heard it said, but there is more than that. A great deal more. Let’s continue to study together and to allow both Christian and Jew to take their specific paths to the gates of God’s Temple.

Note: Quotes from the Gospel of Mark were taken from the Delitzsch Hebrew Gospels, Hebrew/English translation adapted and published by Vine of David from the original 1890 text that was produced by Franz Delitzch and supervised of Gustav Dalman.