From where do we learn from the Torah that changing one’s clothes is a sign of respect?

From where do we learn from the Torah that changing one’s clothes is a sign of respect?

-Shabbos 114a

The verse from Yeshaya 58:13 was already expounded to teach, among other things, that one’s Shabbos clothes should not be like one’s weekday garments (113a). Nevertheless, Rabbi Yochanan is quoted trying to show that this concept is indicated not only from a verse in the prophets, but that it is also rooted in the Torah. Ben Ish Chai explains that based upon this verse from the Torah, there is a practical difference which can be derived regarding the need to wear special clothing on Shabbos.

Daf Yomi Digest

Distinctive Insight

“Suiting up for Shabbos”

Commentary on Shabbos 114a

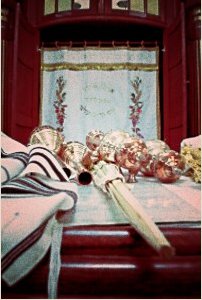

I’ve been pondering a few things lately regarding Judaism and particularly the Messianic sect of Judaism which recognizes Yeshua (Jesus) as the Moshiach (Christ). There are many things about Judaism that I find beautiful and I find myself sometimes drawn to those traditions. In the days when I used to worship on Shabbos and pray while wearing a tallit gadol, there was a “specialness” about it I can’t articulate. Weekday mornings when I would pray shacharit while wearing a tallit and laying tefillin had a texture and a quality about them that I can’t describe. The blessings I recited from the Siddur (which are taken from Hosea 2:21-22 in the Tanakh or verses 19-20 in Christian Bibles) when donning the arm tallit, invoked a particular unity between me and my God that I think Christians miss some of the time.

I will betroth you to Me forever; and I will betroth you to Me with righteousness, with justice, with kindness, and with mercy; and I will betroth you to Me with fidelity, and you will know Hashem.

–Hosea 2:21-22 (Stone Edition Tanakh)

Christians sometimes criticize Jews for all their “man-made traditions” but there is a certain beauty in how observant Jews even prepare themselves for encountering God in prayer. After all, if you were summoned to appear before an earthly ruler, such as a King or President, you would certainly prepare yourself, including dressing for the occasion. Why shouldn’t the same be true if we are summoned to appear before the Ultimate King: God? And after all, Jews are indeed commanded to wear tzitzit (Deuteronomy 22:12) and to, in some sense, wear the Torah (Deuteronomy 6:8).

Hear, O Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. Take to heart these instructions with which I charge you this day. Impress them upon your children. Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up. Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a symbol on your forehead; inscribe them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

–Deuteronomy 6:4-8 (JPS Tanakh)

But as my conversation with Pastor Randy reminded me the other day, there are also commandments and rulings that are beyond my comprehension.

All holy writings may be saved from a fire.

-Shabbos 115a

Perek teaches the laws of saving items from being burned in a fire on Shabbos. On the one hand, our sages realized that if a person is given an unlimited license to save everything he can possibly grab, the person would invariably be driven to try to extinguish the flames, which is a Torah violation… This is why the halachah put a finite limit on what a person is allowed to salvage from a fire. Once this quota of clothing and food is met, the person may not remove anything more from the burning building, even if the particular situation allows the time and conditions to retrieve more.

On the other hand, our sages were lenient to allow saving holy scrolls from a burning building. It is permitted to remove a Torah scroll, for example, to a domain which is normally rabbinically restricted. This is the topic which the first Mishnah discusses.

It is interesting to note that the sages put limits on a person regarding his property pulled from a fire in a building, whereas in other cases we find the opposite. If a person is traveling up to the last minute before Shabbos, and he fails to make it to the city, what should he do with the valuables he is carrying? The Gemara (153a) rules that a Jew in this predicament may instruct a gentile who may be traveling with him to bring the items into the city for him. This is normally a violation of “amira l’nochri – telling a non-Jew to do a melachah for a Jew on Shabbos”, but in this case our sages allowed it, being that they felt that if the Jew would have no recourse, he

might carry the items into the city himself. The Rishonim deal with this apparent inconsistent approach of the halachah to a Jewish person who is faced with a risk to his property. In the case of a fire we limit him although he is not doing any melachah, but when carrying into the city as Shabbos begins, we are lenient.

For a Christian, the problems being posed here and their solutions do not appear on our “radar screens,” so to speak. It’s as if a difficulty was made up for the sake of proposing a solution. Yes, the Jewish people are commanded to observe the Shabbat and to keep it Holy (see Exodus 20:8, Exodus 31:15-17, and Deuteronomy 5:12), but all of the Rabbinic rulings that go along with these commandments are enormously complex, at least to me. How can one even begin to observe Shabbos and remember each and every condition and circumstance that could possibly apply in a flawless manner?

For a Christian, the problems being posed here and their solutions do not appear on our “radar screens,” so to speak. It’s as if a difficulty was made up for the sake of proposing a solution. Yes, the Jewish people are commanded to observe the Shabbat and to keep it Holy (see Exodus 20:8, Exodus 31:15-17, and Deuteronomy 5:12), but all of the Rabbinic rulings that go along with these commandments are enormously complex, at least to me. How can one even begin to observe Shabbos and remember each and every condition and circumstance that could possibly apply in a flawless manner?

But then again, I don’t live in the Orthodox Jewish space, so what do I know?

(I should say at this point that being married to a Jewish wife does give me an insight that a Christian who is not intermarried lacks, but on the other hand, my wife is the first one to say that she’s hardly Orthodox)

I can only imagine that there are many, many Jews who are Shomer Shabbos. I know that after the local Chabad Rebbetzin gave birth to her youngest child on a Friday night, her husband, the Rabbi, walked from the hospital to the synagogue in the middle of the night (since it was Shabbos and he was forbidden to drive or to even accept a ride from another) so that he could be at shul to lead Shabbat services Saturday morning.

I can’t imagine a Pastor ever being in a similar situation and from a Christian’s point of view, even if we had such a restriction, it is very likely that we would depend on the grace of Jesus and under unusual circumstances, overlook the commandment by allowing ourselves to drive or, in the case of a fire, retrieve any of our property we could lay our hands on before the fire could get to it (or to even put out the fire if we could).

Do we admire such dedication to the commandments of God as they are understood in religious Judaism or do we consider observant Jewish people to be bound and gagged by the letter of the Law and also by the commentary on the letter of the Law?

That’s a tough one. Even if we in the church disagree with how Jews choose to obey God, it’s their choice, not ours.

But if those Jews are also Messianic, should we look at the mitzvot any differently? Should we allow ourselves to judge others because they are Jewish and they choose to live a religious Jewish lifestyle?

I’m in no position to do any such thing, but it does bring forth interesting questions. There is not always a single tradition in religious Judaism as to how to perform the mitzvot because there isn’t a single Judaism. Further, there isn’t always agreement between the ancient or modern sages as to how to perform certain of the mitzvot, and so one much choose which tradition to follow, usually based on which Judaism you are operating within.

But those are human choices not necessarily the will of God, unless we want to consider that God is “OK” with all of the variants on Rabbinic teachings, and that is a big “if.”

Setting that aside for a moment, another problem presents itself, but it too is a man-made problem.

I was recently criticized on another person’s blog about the questions I was bringing up as a result of last Wednesday evening’s conversation with Pastor Randy, but the criticism wasn’t coming from anyone Jewish. There is a certain corner of Christianity that believes we Christians are identical to the Jewish people once we come to faith in the Jewish Messiah, at least as far as the mitzvot are concerned…well, sort of. It’s complicated, but the core of their argument is that there is such a thing as a perfect Christianity/Judaism that can be divined solely from the Bible, and that it is possible to practice this very particular form of religion without any (or any excessive) human-created interpretation and set of attendant traditions, and using more than a little theological sleight of hand to “prove” their position.

What’s really interesting is that my critic and his friends who have commented on the matter, didn’t seem to actually read what I’d written. I was asking questions, not making pronouncements, and yet they were actively condemning my “conclusions.” The one thing I can say with certainty though, is that I see no directive for modern Christians to mimic modern Jewish religious behavior in an attempt to worship as if we are in one of Paul’s first century churches or synagogues.

I’m not here to criticize Jewish people or Jewish religious observance. I don’t have the right or the necessary qualifications to render a definitive commentary, only the drive to share my questions and thoughts on the matter, such as they are. I’m not even really criticizing how other Christians choose to view their religious obligations to God, except to the degree that they attempt to impose their personal viewpoints on other Christians and on observant Jews.

To the best of my understanding (and I’m attempting to improve my understanding all of the time), no human being has the ability to perfectly obey God in every single detail, regardless of the religious tradition to which they belong. This was probably as true in the days of Moses, Solomon, and Elijah, as it was true in the days of Jesus and Paul, as indeed, it is true today.

Pastor Randy suggested a very straightforward method of studying the Bible based on the three steps of observation, interpretation, and application. That requires some fluency in Biblical Hebrew and Greek, and lacking much ability in that linguistic arena, I’m already handicapped. This is why I speak with teachers who I respect to discuss and debate them on their insights. This is why I have so many questions.

Pastor Randy suggested a very straightforward method of studying the Bible based on the three steps of observation, interpretation, and application. That requires some fluency in Biblical Hebrew and Greek, and lacking much ability in that linguistic arena, I’m already handicapped. This is why I speak with teachers who I respect to discuss and debate them on their insights. This is why I have so many questions.

But in the end, the advice of another friend of mine must be at the heart of every question and lay the foundation for every answer. In the end, and in the beginning, we should not seek out Judaism or Christianity, but only an encounter with God. This is something that not only are we all capable of, regardless of who we are, but in fact, it is something that we are all commanded to do, because it is God’s greatest desire.

“What you dislike, do not do to your friend. That is the basis of the Torah. The rest is commentary; go and learn!”

-Shabbos 31a

Yeshua answered him, the first of all the mitzvot is: “Hear, O Yisra’el! HaShem is our God; HaShem is one. Love HaShem, your God, with all of your heart, with all of your soul, with all of your knowledge, and with all of your strength.” This is the first mitzvah. Now the second is similar to it: “Love your fellow as yourself.” There is no mitzvah greater than these.

–Mark 12:29-31 (DHE Gospels)

Love God and seek Him and, if you do love God, seek out your fellows and love them, too.