And you shall love Hashem your God …

–Deuteronomy 6:5

And you shall love your neighbor as yourself…

–Leviticus 19:18

Both of these statements are positive commandments. We might ask: How can a commandment demand that we feel something? Since love is an emotion, it is either there or it is not there.

The Torah does not hold that love is something spontaneous. On the contrary, it teaches that we can and should cultivate love. No one has the liberty to say: “There are some people whom I just do not like,” nor even, “I cannot possibly like that person because he did this and that to me.”

We have within us innate attractions to God and to other people. If we do not feel love for either of them, it is because we have permitted barriers to develop that interfere with this natural attraction, much as insulation can block a magnet’s inherent attraction for iron. If we remove the barriers, the love will be forthcoming.

The barriers inside us come from defects in our character. When we improve ourselves, our bad character traits fall away, and as they fall away, we begin to sense that natural love which we have for others and for God.

Today I shall…

…try to improve my midos (character traits), so that I will be able to feel love for God and for my fellow man.

-Rabbi Abraham J. Twerski

from “Growing Each Day” for Cheshvan 7

Aish.com

The first thing that attracted me to this daily “devotional” of Rabbi Twerski’s is the obvious parallel to the teaching of the Master:

One of the scholars heard them arguing and drew near to them. He saw that he answered well, and he asked him, “What is the first of all of the mitzvot?”

Yeshua answered him, “The first of all the mitzvot is: ‘Hear O Yisra’el! HaShem is our God; HaShem is one. Love HaShem, your God, with all of your heart, with all of your soul, with all of your knowledge, and with all of your strength.’ This is the first mitzvah. Now the second is similar to it: ‘Love your fellow as yourself.’ There is no mitzvah greater than these.”

–Mark 12:28-31 (DHE Gospels)

I don’t know if R. Twerski is at all familiar with the Apostolic Scriptures (probably not, but who knows) or even the portion I quoted above, but it seems amazing that nearly two-thousand years after the Master uttered this teaching, the same source material from the Torah should be linked together in a very similar manner by an Orthodox Jewish Rabbi and Psychiatrist.

Then, as I was performing my Shabbat devotionals, I came across the following:

The orlah, “foreskin,” symbolizes a barrier to holiness. Adam HaRishon was born circumcised (see Avos D’Rabbi Nassan 2:5) because he was as close as a physical being can possibly be to Hashem. So great was Adam at the time of his creation, that the angels thought he was a Divine being to whom they should offer praise. Thus, he was born circumcised; there was no orlah intervening between him and Hashem. Even the organ that represents man’s worst animal-like urges was totally harnessed to the service of Hashem.

-from the Mussar Thought for the Day, p.151

for Shabbos: Parashas Lech Lecha

A Daily Dose of Torah

Now compare the above quote to the next one:

Episcopal lesbian theologian Carter Heyward, whose work we briefly noted in part I, has described her project this way: “I am attempting to give voice to an embodied — sensual — relational movement among women and men who experience our sexualities as a liberating resource and who, at least in part through this experience, have been strengthened in the struggle for justice for all.” Heyward and others…are attempting nothing less than a recovery of the physical, embodied, and erotic within Christian traditions that have traditionally suppressed them. Building a theology of relationality that is reminiscent of the work of Jewish philosophers Martin Buber and Emmanuel Levinas, Heyward has proposed a spiritual valuation of eros — which she defines as “our embodied yearning for mutuality.” Openness to embodied love opens us to other people, the biological processes of the universe, and to God. Thus, Heyward writes, “my eroticism is my participation in the universe” and “we are the womb in which God is born.”

-Jay Michaelson

Chapter 17: “And I have filled him with the spirit of God…to devise subtle works in gold, silver, and brass,” p.156

God vs. Gay: The Religious Case for Equality

I previously quoted that paragraph in my third and final review of Michaelson’s book, but I think it bears repeating.

When Rabbi Twerski, (unintentionally) echoing the teachings of the Master speaks of loving God and loving his neighbor, he isn’t talking about erotic love or eroticizing our relationship with God or our fellow human being. When he writes of our “innate attractions to God and to other people,” he isn’t saying that these are sexual or romantic attractions any more than Messiah was speaking of sex.

The Mussar thought from the Artscroll “Daily Dose” series speaks of the male sexual organ as representing “man’s worst animal-like urges.” Throughout his book, Michaelson favorably compared people to animals in that both expressed their sexuality with same-sex partners, and yet we see that the traditional Orthodox Jewish viewpoint is to separate man from the animal world.

Even setting the midrash aside, the Mussar teaches that man is to be considered unique and separate from animals and further, that the single worst urge a man must bring under control in the service of Hashem is his sexual urge.

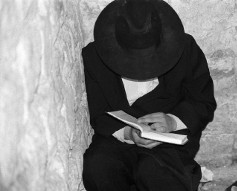

This is why Bible study in general and Torah study in specific is so important, because it grounds us in the Word of God and thus in righteousness and holiness. It points to our flaws and urges us to self-discipline. It’s like reading a health and weight loss manual while sitting down in an “all-you-can-eat” buffet. You are immersed in temptation, and yet you hold a reminder in your hands to resist because giving in to the world around you leads (extending the metaphor) to poor health, suffering, and premature death.

This is why Bible study in general and Torah study in specific is so important, because it grounds us in the Word of God and thus in righteousness and holiness. It points to our flaws and urges us to self-discipline. It’s like reading a health and weight loss manual while sitting down in an “all-you-can-eat” buffet. You are immersed in temptation, and yet you hold a reminder in your hands to resist because giving in to the world around you leads (extending the metaphor) to poor health, suffering, and premature death.

The death I’m speaking of is a spiritual death if we attempt to conform our faith to the standards of the world around us rather than conforming ourselves to the standards of God.

None of this demands that we must fail to love the people around us, even those who are very different, such as gay people, and since I’m straight, gay people are different, at least as far as that one quality or trait is concerned. But as I saw by the time I reached the end of the Michaelson book, what he was driving at wasn’t just the equalization of the participation of straight and gay people in the church and synagogue, he was talking about the total transformation of the house of God. Reading Rabbi Twerski and the Mussar for Lech Lecha on Shabbos made it abundantly clear that what Michaelson was proposing, even with sincere intentions, was not at all consistent with how God defines love.

I’m sorry to keep dragging this out and as far as my current intentions go, this is the last blog I’ll dedicate to Michaelson in specific and the topic of gays in the community of faith in general. But having, by necessity, entered, to some small degree, the world of Jay Michaelson’s thoughts and feelings by reading his book, I needed to pull myself back out and re-establish myself in the presence of God through the study of His Word.

We are commanded to love other people including those we find in the LGBTQ community. R. Twerski is correct in that we need not construct barriers between them and us in terms of our compassion. That said, there is a barrier between a holy life and a profane one. In the ekklesia of Messiah, as mere human beings who are daily bombarded with the excesses of the world around us, we constantly struggle with those excesses and with our own natures to seek to remain on the path God has set before us. I know I don’t always succeed and by God’s standards I am a complete failure.

But I can’t give up and either abandon my faith or seek to morph it into something consistent with my external environment, society, and culture. Holiness must be protected and thus we maintain a barrier, not one that doesn’t permit the expression of love, but one that keeps us from getting lost in a highly liberal and distorted use of the term.

When a parent loves a child, it doesn’t mean that parent is ultimately permissive and allows the child to do whatever he or she wants simply because it makes them feel good. We say “no” a lot, and even if the child cries or yells at us and tells us we’re being “mean”, we know we are actually being loving and protective.

That’s what God does to us and those are the commandments we not only obey, but support, uphold, and teach. Even if people like Michaelson want to call me “mean” for doing so, this is how God teaches the community of faith to do love. It’s a loving thing to live inside the standards of God, and as tempting as it may be, it isn’t love to believe you can be right with God outside of the house built by those standards.

Two more paragraphs from the Mussar thought from which I quoted above will finish the picture (pp.151-2):

Two more paragraphs from the Mussar thought from which I quoted above will finish the picture (pp.151-2):

When Adam sinned, however, he caused his nature to change. Before his sin, godliness had been natural for him, and sin had been repulsive, bizarre, and foreign. Once he disobeyed Hashem, however, he fell into the traps of illicit desire and self-justification. Suddenly, temptation became natural to him, and Hashem became distant; and when Hashem reproached him for having sinned, Adam hastened to defend himself rather than admitting his sin and repenting. After his fall, the angels had no trouble recognizing his human vulnerability.

In several places, the Torah mentioned … “the foreskin of the heart” (see, for example, Devarim 10:16). This is the non-physical counterpart of the physical foreskin, man’s urges and desires that attempt to bar him from achieving true service to Hashem. We remove the physical foreskin as an indelible act of allegiance, demonstrating our resolve to do the same for the spiritual barriers. Nevertheless, the Torah tells us that ultimately it will be Hashem Who will complete the removal of this spiritual foreskin (see ibid. 30:6) after we have done our utmost, and this will take place at the time of the ultimate redemption.