Therefore leaving the elementary teaching about the Christ, let us press on to maturity, not laying again a foundation of repentance from dead works and of faith toward God, of instruction about washings and laying on of hands, the resurrection of the dead, and eternal judgment. And this we will do if God permits.

–Hebrews 6:1-3 (ESV)

On the subject of Baptism and Instructions regarding Immersions in Hebrews 6, we look at the evidence from early Christian documents. Find out how the second-century Christians welcomed new converts into the body of Messiah. This teaching contains quotations from Justin Martyr’s First Apology, from the Didache, and from the Apostolic Constitutions. The quotations are available in the PDF document below titled “Initiation Texts.”

-D. Thomas Lancaster

Sermon Twenty-three: Laying on of Hands

Originally presented on July 7, 2013

from the Holy Epistle to the Hebrews sermon series

This is one of the shorter sermons in the series (barely thirty minutes long) as well as a short chapter in Lancaster’s book Elementary Principles. In this sermon, Lancaster proposes to show how the basic foundational principles he has covered in previous sermons, particularly as mapped to the Didache, were carried forward in time to the second and even the third century CE, using classic Christian documents.

To review these first four principles covered so far:

- Repentance from dead works (sin)

- Faith toward God (through Messiah)

- Instruction about washings (elemental instructions of the faith prior to immersion in the name of Messiah)

- Laying on of hands (to confer discipleship and possibly the Holy Spirit)

Lancaster outlines the challenge in what he’s trying to do, since the writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews felt the six principles were so basic that he didn’t bother to write them down. Neither did any of the other New Testament writers. Lancaster states that he believes Paul taught these principles orally, and that by the time the Hebrews writer was composing his letter, it was just assumed everyone knew all about this “milk”.

But we know nothing about them today since they weren’t written down in much detail, if at all.

Lancaster turns to three Christian documents to prove his point that these elemental principles were indeed carried forward in time with Christianity:

- Justin Martyr’s “First Apology”

- The Didache

- The Apostolic Constitutions

I’ve posted the link above to the relevant document, but here it is again. Click the link to open the PDF and you’ll find the list of documents and specific quotes Lancaster uses.

I’ve posted the link above to the relevant document, but here it is again. Click the link to open the PDF and you’ll find the list of documents and specific quotes Lancaster uses.

He uses these quotes to map back to the specific phrases in Hebrews 6:1-3 that list the six elementary principles.

Justin Martyr was writing around 150 CE and Lancaster paints a brief portrait of Martyr’s environment. The Bar Kochba rebellion ended in failure. Jerusalem has been destroyed, Herod’s Temple razed, and a pagan temple built on its ruins. The Jewish people have been exiled and in the midst of all that, the new religion Gentile Christianity and the original Jewish Messianic movement of “the Way” have just gone through a nasty divorce.

Martyr wrote his document, which we call “The First Apology” to the Roman Emperor as an appeal that the Empire stop persecuting Christians.

It’s Lancaster’s contention that these later Christian documents, especially the Didache, were based on much earlier writings and oral traditions going back to the second and even the first century, and perhaps even reflecting the teachings of the apostles.

Lancaster’s handout is organized as follows:

- Instructions before Immersion (Apostolic Constitutions 7.39.2-4)

- Preparing for Immersion (Justin Martyr, First Apology 61)

- Fasting Before Immersion (Didache 7:1-4)

- The Immersion (Justin Martyr, First Apology 61, Didache 7:1-3)

- The Investiture (Laying on of Hands) (Justin Martyr, First Apology 65)

- Prayer for the New Disciple (Apostolic Constitutions 8.6.5-8)

- Breaking the Fast (Justin Martyr, First Apology 65)

I won’t go into all of the details. You can read the PDF and listen to Lancaster’s sermon (only half an hour) for the details, but there are some questions.

What Did I Learn?

Lancaster has a talent for pulling together information and documents from (sometimes) widely disparate sources and then attempts to make them work together. To the degree that he’s comparing ancient Christian documents, I can see where he’s going, but Lancaster admits that these are documents originating in different time periods, so care should be taken in making very close comparisons.

Also, he states that the “nasty divorce” between Jesus-believing Jews and Gentile Christians had already occurred, and except for arguably the Didache, the other two documents Lancaster is using are from the Gentile side of the equation. Why is that important? Because Lancaster’s purpose in this investigation is to uncover the practices of ancient Messianic Judaism so we can practice this way, too.

Also, he states that the “nasty divorce” between Jesus-believing Jews and Gentile Christians had already occurred, and except for arguably the Didache, the other two documents Lancaster is using are from the Gentile side of the equation. Why is that important? Because Lancaster’s purpose in this investigation is to uncover the practices of ancient Messianic Judaism so we can practice this way, too.

But a lot of what he introduces isn’t from, strictly speaking, Jewish sources. These are interpretations made by Christian Gentiles who, after the aforementioned “nasty divorce,” have no reason to spread any sort of love for their Jesus-believing Jewish counterparts.

In fact, quoting Paul Meier from his recent Messiah Journal article which I reviewed:

Marcion’s contemporary Justin Martyr was one of the first to articulate a position of replacement theology, also known as displacement, transfer, or supersessionist theology. Avner Boskey succinctly described this theological stream as “an expression of Gentile triumphalism in the early church.”

-Meier, pg 81

I’m not saying Lancaster is wrong, and he’s certainly more studied and better educated in these matters than I am, but I don’t want to get too excited about drawing firm conclusions from a little bit of documentation and a lot of supposition.

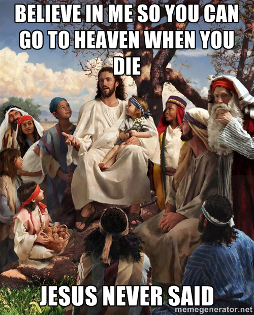

That said, I don’t know if it would hurt to add some or a lot of this structure to modern Christian practice. Think about it. As you follow the train of Lancaster’s logic and observe the linear fashion by which an ancient novice disciple of the Master is initiated, educated, and baptized into the faith, becoming a Christian in the first and second centuries was a much more formal affair than it is in Evangelical Christianity today.

The initiate had to give a great deal of serious consideration to their decision to become a disciple, study quite a bit, deeply repent of their sins, dedicate themselves to a life-long pattern of righteousness, and be willing to take a solemn vow before God prior to baptism.

Can you say that all or even most professing Christians today take their faith that seriously and were that prepared even before baptism? How many Christians today came to faith simply by raising their hand at a Christian camp meeting or answering an altar call at church? Even after years or even decades, many Christians still may just be “going with the flow” and have never come to the realization of what they’ve committed to.

This is where I see Lancaster making his point very strongly. Today, we don’t even know much about what the writer of the Book of Hebrews took for granted to be the “milk”, the “baby food”, the six elemental principles of the faith. They were so basic and so well-known, that they were never documented, at least not in any text we have with us today.

Lancaster’s point, as I understand it, is that we should return to the formal seriousness and dedicated preparedness of inducting novices into true discipleship, taking time to make sure that the person is ready to enter this tremendously august relationship, and only after all that, actually proceed forward, pressing “on to maturity” (Hebrews 6:1).

Lancaster’s point, as I understand it, is that we should return to the formal seriousness and dedicated preparedness of inducting novices into true discipleship, taking time to make sure that the person is ready to enter this tremendously august relationship, and only after all that, actually proceed forward, pressing “on to maturity” (Hebrews 6:1).

Lancaster is quite serious about rediscovering the ancient teachings and practices of Messianic Judaism as it existed in the first century and into the second, and that desire has merit, but is it do-able? All of the other ancient streams of Judaism from that era either were extinguished or progressed forward, morphing and evolving across the long centuries. What was Pharisaic Judaism in the days of Jesus and Paul is now called “Rabbinic Judaism,” although there are indeed multiple Judaisms in our day and age.

I guess I could say that Orthodox Judaism (although there is no single expression of Orthodox Judaism in modern times) is the most direct inheritor of ancient Pharisaic Judaism, but you many not be able to directly compare the two. So much has happened, the definition of practicing Judaism in Orthodox thought is quite different from how the Pharisees saw themselves.

Should we contrast modern Messianic Judaism with the ancient Jewish practice of “the Way” in the same manner? If “the Way” was most closely compared to the Pharisees in the first century, what does that say about the relationship between modern Orthodox Judaism and Messianic Judaism or what should it say?

I don’t know that Lancaster has set a completely achievable goal for himself and particularly for his (mostly Gentile) congregation. If he’s been lobbying for a mikvah to be built for the past several years but support hasn’t been overwhelming among his constituency, is that indicative of how difficult it is for we modern Gentiles coming out of our church experiences to fully embrace a strongly observant Jewish lifestyle?

I’m not trying to be a wet blanket, but even most of the Messianic Gentiles in Messianic Judaism may not be ready to take on board the full yoke of Torah, either as it was expressed in the days of Paul, or as we understand it in Orthodox Judaism today, assuming that is the model to be followed.