Therefore let us leave the elementary doctrine of Christ and go on to maturity, not laying again a foundation of repentance from dead works and of faith toward God, and of instruction about washings…

–Hebrews 6:1-2 (ESV)

Hebrews 6:1-3 identifies “instructions about washings” as one out of six fundamental, elementary teachings about the Messiah. Does this refer to Baptism? Learn about the Jewish practice of immersion in a mikvah and discover evidence of early, apostolic-era catechism prior to immersion.

Includes a short introduction to the Didache.

-D. Thomas Lancaster

Sermon Twenty-one: Instructions About Washings

Originally presented on June 22, 2013

from the Holy Epistle to the Hebrews sermon series

Instructions about washings (plural). After a brief summary of the first two elementary principles, “Repentance from dead works” and “Faith toward God,” Lancaster continues with the third, “Instructions about washings”. This is often considered in normative Christianity to refer to baptism and easily dismissed as such. The King James Version of the Bible even renders the phrase as “the doctrine of baptisms,” but…

The translators of the English Standard Version, like many Bible scholars, recognized that the Greek word “baptismon” does not sound as if it’s talking about Christian baptism, because it appears in the plural form, whereas Christians are baptized only once. Furthermore, in other places in the New Testament, the word “baptismos” refers to ceremonial purification rituals of immersion in a mikvah. Several scholars looked at this passage and said, “I don’t think he’s talking about Christian baptism. I think he’s talking about Jewish purity rituals.”

-D. Thomas Lancaster

“Chapter 5: Instruction About Washings,” pg 64

Elementary Principles: Six Foundational Principles of Ancient Jewish Christianity

This book leverages much of the material from Lancaster’s sermons on these elementary principles from his “Hebrews” series and is a good companion to use with these audio recordings.

Here we learn that it is highly likely that these “immersions” mentioned in Hebrews 6:2 do not reference the modern Christian concept of baptism, since a Christian is only baptized once and the Greek word used in the text is clearly plural. It is more likely that the writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews is talking about Jewish ritual purity rites using the mikvah, since the writer (according to Lancaster) is a Jew writing to other Jewish believers in Messiah Yeshua.

Lancaster presents some historical and archeological information regarding ancient immersion pools in the late Second Temple period to illustrate that it was extremely common for Jews to immerse on any number of occasions for the purpose of ritual purity, including participation in Temple sacrifices.

He also takes this opportunity to go on a small “rant” about how Christianity has fundamentally misunderstood the nature and character of baptism, and he ran through a litany of things that he believes the Church has gotten all wrong (he was talking too fast for me to take notes, so if you want to hear his reasons, you’ll have to listen to the recording). I don’t think Lancaster was trying to “diss” the Christian Church so much as he was being passionate about what he sees as the truth of the early history of Jesus-believing Judaism and how it’s been distorted by subsequent Gentile Christianity.

As an aside, Lancaster has been lobbying to build a mikvah at Beth Immanuel for the last seven years (eight years as of this writing) but there hasn’t been much of a response. That reminded me of something I just read in Sue Fishkoff’s book The Rebbe’s Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch. Often, when a Chabad family moves into an area without an Orthodox Jewish presence, their first and overriding priority is to build a mikvah, particularly for the use of the Rabbitzin in relation to the laws of ritual family purity. The reaction from the local Jewish community to the Chabad’s fundraising efforts to build a mikvah (and they’re not cheap) is just as lukewarm. What does Lancaster and the Chabad know about the mikvah that the rest of us don’t, or is that a sad question to ask as connected to “elementary principles” of our faith?

As an aside, Lancaster has been lobbying to build a mikvah at Beth Immanuel for the last seven years (eight years as of this writing) but there hasn’t been much of a response. That reminded me of something I just read in Sue Fishkoff’s book The Rebbe’s Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch. Often, when a Chabad family moves into an area without an Orthodox Jewish presence, their first and overriding priority is to build a mikvah, particularly for the use of the Rabbitzin in relation to the laws of ritual family purity. The reaction from the local Jewish community to the Chabad’s fundraising efforts to build a mikvah (and they’re not cheap) is just as lukewarm. What does Lancaster and the Chabad know about the mikvah that the rest of us don’t, or is that a sad question to ask as connected to “elementary principles” of our faith?

So, what were these “instructions about immersions?” How to build a mikvah? The mechanics of how to baptize? At one point, Lancaster might have said “yes”, but then he realized how “dumb” an answer that was…a typical “Goy” answer.

Jews would have been already well acquainted with the rituals surrounding the mikvah, the occasions when one had to engage in ritual purity rites and so forth. This wasn’t a mystery. While Gentiles may have needed those sort of instructions, they would have been less than useless to the Jewish believers.

Lancaster shared his own revelation. When reading a commentary on this part of the Book of Hebrews, he learned that these instructions about immersions could be referred to as “Catechetical Instructions for Conducting the Baptismal Rite.”

When I was a pre-teen and into mid-teens, my parents regularly took me to a Lutheran church. Lutheran churches, like Catholic churches, put their young people into a two-year Confirmation class where we studied Catechism, which according to Wikipedia is “a summary or exposition of doctrine and served as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adult converts.”

That’s what Lancaster thinks these “instructions about immersions” are. Not directions on how to immerse or baptize, but the very basic instructions a new believer had to know before being immersed in the name of the Messiah as a full disciple.

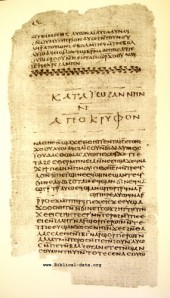

Lancaster than referenced the best known ancient “catechism” we have access to: the Didache.

Last fall, I read and wrote about First Fruits of Zion’s (FFOZ) Toby Janicki’s article “The Didache: An Introduction” published in Messiah Journal. Since then, I purchased a copy of the Didache along with a commentary and wrote several blog posts on the topic which can be found here.

While Lancaster isn’t saying the Didache we have is the actual set of instructions being referred to in Hebrews 6:2, they may very well be related. It’s clear that the Didache was written for new Gentile “novices” in Yeshua-discipleship in order to prepare them to be immersed into Messiah by being initiated in the teachings of the Master. These instructions may have begun as oral instructions that accompanied the delivery of the Acts 15 “Jerusalem Letter” to the various Jesus-believing Gentile communities in the diaspora.

I should mention here that as Lancaster correctly states, the Didache’s initial discovery prompted accusations of forgery and fraud, since the document didn’t match the theology and doctrine of any Christian denomination and was seen as “too Jewish”. But today, most Christian scholars admit that the document most likely originated within one or two decades of the destruction of Herod’s Temple, written probably by Jewish disciples of Jesus for newly minted Gentile disciples. As I mentioned though, these written instructions could well have been preceded by an oral equivalent and could possibly have first come from the apostles themselves.

I should mention here that as Lancaster correctly states, the Didache’s initial discovery prompted accusations of forgery and fraud, since the document didn’t match the theology and doctrine of any Christian denomination and was seen as “too Jewish”. But today, most Christian scholars admit that the document most likely originated within one or two decades of the destruction of Herod’s Temple, written probably by Jewish disciples of Jesus for newly minted Gentile disciples. As I mentioned though, these written instructions could well have been preceded by an oral equivalent and could possibly have first come from the apostles themselves.

However, the Jewish disciples may have required a similar, parallel set of instructions to familiarize them with the teachings of Messiah and what it is to be a Jew preparing for a lifelong commitment to “take up their cross” and follow Moshiach, even unto death.

So look at it like this.

The newly initiated Jewish believers were first taught the very elementary principles of Yeshua-faith starting with repentance from dead works (sin) and then faith toward God as specific to Messianic devotion. Once they had mastered those first two principles, they were ready for the third, the basic instructions required for them to prepare to be immersed into the name of Messiah, which constitutes a vow of eternal fidelity.

Jewish people would immerse in the mikvah an untold number of times over the course of a lifetime, so immersing for ritualistic reasons was hardly novel. However, John specifically practiced an immersion of repentance (Matthew 4:17, Acts 19:4) and the Master commanded another specific immersion:

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” (emph. mine)

–Matthew 28:19-20 (NASB)

The immersion in the name of Messiah fits in perfectly with what the Church calls “the Great Commission” but put back into a Jewish context, the ritual immersion in Messiah’s name makes a great deal more sense.

For Lancaster, and I agree with him, a serious time of preparation must have been thought necessary before formally becoming a disciple of the Master. This was probably quite similar to the proselyte ritual process Gentiles experienced when converting under other Jewish sects. Even today, a Gentile converting to Judaism, particularly Orthodox Judaism, undergoes a time of intense preparation and study under the supervision of a Rabbi, and must past several tests before becoming circumcised (for males) and immersing in the mikvah as the final rite in becoming a Jew.

For Lancaster, and I agree with him, a serious time of preparation must have been thought necessary before formally becoming a disciple of the Master. This was probably quite similar to the proselyte ritual process Gentiles experienced when converting under other Jewish sects. Even today, a Gentile converting to Judaism, particularly Orthodox Judaism, undergoes a time of intense preparation and study under the supervision of a Rabbi, and must past several tests before becoming circumcised (for males) and immersing in the mikvah as the final rite in becoming a Jew.

It seems very reasonable to believe that in ancient Yeshua-faith, the Gentile “converts” were required to undergo a similar procedure, although I’m sure there were exceptions (Acts 8:25-40, Acts 10:44-48).

Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after Me cannot be My disciple. For which one of you, when he wants to build a tower, does not first sit down and calculate the cost to see if he has enough to complete it?

–Luke 14:17-28 (NASB)

What Did I Learn?

Actually, I felt there were things Lancaster only hinted at in his sermon. If he believes the Christian Church has gotten baptism all wrong, particularly as far as only being baptized once, what other applications might there be for immersion among the body of believers? I’m sure that Messianic Jewish disciples of the Master could and would immerse for the same reasons as other observant Jews, but what about the “Messianic Gentiles?” If we immerse in the name of Messiah once, on what other occasions should Gentiles enter the mikvah?

It had never occurred to me to apply Matthew 28:19-20 to Hebrews 6:2 but now it makes a great deal of sense to connect the two scriptures. I’m sure an entire study could be done applying what we think of as “baptism” in Christianity to ancient and modern concepts of immersion in the mikvah.

This also made me think of my own immersion. In August 1999, my entire family was immersed, under the auspices of a local Hebrew Roots congregational leader, in the Boise River. The following month, my life started to dramatically fall apart in such a spectacular manner that it would take years for me and my family to recover.

My interpretation is that God takes immersion into the name of Messiah quite seriously, even if the people being immersed don’t know what they’re doing (and I certainly didn’t). God delivered the consequences of my ill-conceived decision directly into my lap and it wasn’t pleasant at all. A lot of re-writing of my script had to be done and it’s not finished yet, not by a long shot. The finger of God is still writing on my heart and slowly converting it from a thing of stone to a heart of beating flesh and blood.

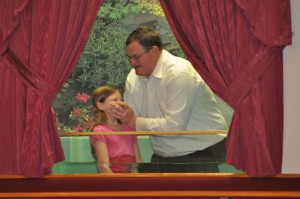

How many churches prepare their people with a dedicated set of instructions and tutelage before determining they are ready for this level of life-long commitment? I know in the church I attend there is some sort of formal preparation, but I fear for the sake of the children, some age nine and younger, who are deemed ready to understand what it is to count the cost, take up their crosses, and follow Jesus, even unto death. How could you be nine years old and possibly comprehend who you’re vowing to obey and what the consequences will be?

Lancaster says he believes our churches are filled with “false converts,” people, like me, who consent to being baptized without any real idea of what that truly means. We have very few formal vows in Christianity left. The one you most likely think of is the wedding vow, but the staggering divorce rate in the Church indicates even that one is not well understood.

Lancaster says he believes our churches are filled with “false converts,” people, like me, who consent to being baptized without any real idea of what that truly means. We have very few formal vows in Christianity left. The one you most likely think of is the wedding vow, but the staggering divorce rate in the Church indicates even that one is not well understood.

When we consent to being immersed in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit of God, we had better know what we’re doing, and if we haven’t been prepared adequately for the commitment, then even though we are acting out of ignorance, God will hold us accountable.

Lancaster believes we should return to instructing new believers in the elemental principles of our faith which might include some familiarity with the Didache or something patterned after it. I think he’s right. People declare Christ as Lord and Savior and are baptized in his name far too casually in our day. I think thousands upon thousands of people in the Church are in a lot of trouble and don’t even realize it.