May He Who knows what is hidden accept our call for help and listen to our cry.

May He Who knows what is hidden accept our call for help and listen to our cry.

-Siddur

The Talmud states that a person may be coerced to perform a mitzvah even if it is required that the mitzvah be done of one’s own volition (Rosh Hashanah 6a).

But are not coercion and volition mutually exclusive? Not necessarily, explains Rambam. Inasmuch as the soul of the Jew intrinsically wishes to do the Divine will, and it is only the physical self – which is subject to temptation – that may be resistive, the coercion inflicted upon the person overcomes that external resistance. Thus, when one performs the mitzvah, it is with the full volition of the inner self, the true self, for at his core, every Jew wishes to comply with the mandates of the Torah.

There is a hidden part of us, to which we may have limited access, yet we know it is there. When we pray for our needs, said Rabbi Uri of Strelisk, we generally ask only for that which we feel ourselves to be lacking. However, we must also recognize that our soul has spiritual needs, and that we may not be aware of its cravings.

We therefore pray, said Rabbi Uri, that God should listen not only to the requests that we verbalize, but also to our hidden needs that are very important to us – but which He knows much better than we.

Today I shall…

try to realize that there is a part of me of which I am only vaguely aware. I must try to get to know that part of myself, because it is my very essence.

-Rabbi Abraham J. Twerski

“Growing Each Day, Tishrei 26”

Aish.com

The commentary of Rabbi Twerski will no doubt seem strange to most Christians. How can one be forced to obey God and why split your personality into two parts, the one tempted by the physical world, and the “true self” who “wishes to comply with the mandates of the Torah?” Of course, Christianity commonly splits life into the secular and the spiritual and recognizes that the believer constantly struggles between human desire and obedience to God.

But in our heart of hearts, as children of God, we do want to please our Father and obey our Savior in Heaven. It’s just a matter of what that means. For a Christian, devotion to God is largely an internal process. Sure, Christians go to church and commune with their fellows, but prayer and belief are at the core of the Christian faith. For Jews, it seems almost the opposite. Performing the mitzvot and obedience to the commandments are at the heart of Jewish devotion to God. Of course, prayer is a very important mitzvah, but in religious Judaism, faith is not so much what you believe but what you do.

Torah and mitzvot encompass man from the instant of emergence from his mother’s womb until his final time comes. They place him in a light-filled situation, with healthy intelligence and acquisition of excellent moral virtues and upright conduct – not only in relation to G-d but also in relation to his fellow-man. For whoever is guided by Torah and the instructions of our sages has a life of good fortune, materially and in spirit.

“Today’s Day”

Tuesday, Tishrei 27, 5704

Compiled by the Lubavitcher Rebbe

Translated by Yitschak Meir Kagan

Chabad.org

I read Psalm 119 on Shabbat from the Stone Edition Tanakh (Jewish Bible) and was particularly taken by the psalmist’s devotion to God and the Torah:

Praiseworthy are those whose way is perfect, who walk with the Torah of Hashem. Praiseworthy are those who guard His testimonies, they seek Him wholeheartedly. They have also done no iniquity, for they have walked in His ways. You have issued Your precepts to be kept diligently. My prayers: May my ways be firmly guided to keep Your statutes. Then I will not be ashamed, when I gaze at all Your commandments. I will give thanks to You with upright heart, when I study Your righteous ordinances. I will keep Your statues, O, do not forsake me utterly.

–Psalm 119:1-8 (Stone Edition Tanakh)

I find these words and their meaning to be very beautiful, and they weave for me, a life of study, contemplation, and devotion to the Words and ways of God. And yet, they seem (apparently) at odds with how Christians see obedience to God:

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made us both one and has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two…

–Ephesians 2:13-15 (ESV)

The Jewish psalmist builds up and praises God’s “righteous ordinances” and “statues,” while Paul (apparently) in his letter to the Ephesians declares that “by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances” the psalmist holds so dear, Christ obliterates the “dividing wall of hostility” between Gentile and Jewish believers, in order to create “one new man in place of two.”

However you choose to interpret that portion of Ephesians 2, it seems as if the traditional viewpoints of how to cherish and obey God between the Jew and the Christian are at odds (and aren’t the Psalmist and Paul also at odds?).

I periodically converse with and debate (click the link and scroll down to the comments section) with Christians (mostly Gentiles and a very few Jews) who attempt to reconcile these two perspectives into one, combining Christian faith through belief in the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ with an attempt to obey the mitzvot as a response to that faith, thus imitating the Jewish Messiah in his Judaism, though with 21st century rather than 1st century Jewish methods. There is a great debate between Messianic Judaism (and probably other forms of Judaism if they would choose to enter the online discussion) and what is commonly referred to as “One Law” Christianity, regarding how proper this approach is, but I’m not here to discuss those matters today…at least not exactly.

I’ll take it for granted that all servants of the Master want to obey God. The question then becomes how is this done. For the traditional Jew, it is through the mitzvot. For the traditional Christian, it is through belief and prayer. Messianic Jews tend to take on the practices of the other Judaisms, and we see that the Messianic Jewish Rabbinical Council (which represents a sizeable portion of American Messianic Jews but cannot speak for the entire movement), according to their Standards of Observance (PDF), is strongly aligned with Conservative and Reform Judaism in terms of halakhah, however, as a Jewish body who has accepted Jesus Christ as the Jewish Messiah within a Jewish conceptual and practical context, there are other considerations:

I’ll take it for granted that all servants of the Master want to obey God. The question then becomes how is this done. For the traditional Jew, it is through the mitzvot. For the traditional Christian, it is through belief and prayer. Messianic Jews tend to take on the practices of the other Judaisms, and we see that the Messianic Jewish Rabbinical Council (which represents a sizeable portion of American Messianic Jews but cannot speak for the entire movement), according to their Standards of Observance (PDF), is strongly aligned with Conservative and Reform Judaism in terms of halakhah, however, as a Jewish body who has accepted Jesus Christ as the Jewish Messiah within a Jewish conceptual and practical context, there are other considerations:

In addition to Tanakh, we as Messianic Jews have another authoritative source for the making of halakhic decisions: the Apostolic Writings. Yeshua himself did not act primarily as a Posek (Jewish legal authority) issuing halakhic rulings, but rather as a prophetic teacher who illumined the purpose of the Torah and the inner orientation we should have in fulfilling it. Nevertheless, his teaching about the Torah has a direct bearing on how we address particular halakhic questions. As followers of Messiah Yeshua, we look to him as the greatest Rabbi of all, and his example and his instruction are definitive for us in matters of Halakhah as in every other sphere.

In addition, the Book of Acts and the Apostolic Letters provide crucial halakhic guidance for us in our lives as Messianic Jews. They are especially important in showing us how the early Jewish believers in Yeshua combined a concern for Israel’s distinctive calling according to the Torah with a recognition of the new relationship with God and Israel available to Gentiles in the Messiah. They also provide guidelines relevant to other areas of Messianic Jewish Halakhah, including (but not restricted to) areas such as distinctive Messianic rites, household relationships, and dealing with secular authorities.

If all that looks complicated, it’s important to remember that even traditional Christians struggle to understand how best to obey God and where we fit into His Holy plan.

But is it really so hard to understand at its core. Even for the non-Jewish Christians who are drawn to the Torah, is there such a great distance between them and their brothers and sisters in the church? For that matter, is there such a great distance behaviorally between religious Judaism in any of its forms and the body of Christian believers who also desire to obey God with all their hearts?

Let’s take a look at some of those behaviors of obedience. I’ll be using the list of the 613 mitzvot Jews believe God gave to Israel at Sinai which were (much) later codified by Maimonides. I’m specifically referencing the list found at Judaism 101.

It should be noted that exactly how one is to obey the mitzvot isn’t always a straightforward affair. Particularly in Orthodox Judaism, a large, documented body of rulings, judgments, and interpretations collectively known as the Talmud defines the methods and procedures whereby a Jew can fulfill the various mitzvot (most of which cannot be performed without the Temple in Jerusalem, an active Levitical priesthood, a Sanhedrin court system, or outside of the Land of Israel), but I won’t be going into those details as they are far outside the scope of this humble blog post. I should almost mention that the various Judaisms (Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and so on) have differing approaches to halakhah and the mitzvot, so their prioritization and interpretation of how, when, or if to perform various acts of obedience will not be the same among all the modern “Judaisms”.

Naturally, I can’t list all 613 commandments so I’ll take just a few examples to examine.

To know that God exists (Ex. 20:2; Deut. 5:6)

Exodus 20:2 in the Stone Edition Tanakh states:

I am Hashem, your God, Who has taken you out of the land of Egypt, from the house of slavery.

That doesn’t sound like a command or a mitzvot (something you can do) to most Christians, but for a Jew, it’s the first of the Ten Commandments. If you think about it for a second, you really can’t obey God at all unless you know that He exists and you know that He is God. Once you accept those things, then the rest of the commandments can follow.

While God didn’t bring the Christians out of the Land of Egypt and the “house of slavery” (except in a metaphorical sense when Jesus delivered us from the slavery of our sins), He is just as much a God to us as He is to the Jewish people. In fact, whether the rest of the world chooses to believe or not, God is God to all of humanity since we were all made in His image. If this is a commandment of God, then by definition, both Jews and Christians must obey.

To give charity according to one’s means (Deut. 15:11)

Deuteronomy 15:11 states in the Tanakh:

You shall surely open your hand to your brother, to the poor, and to your destitute in your Land.

The last portion of this verse, within its context, seems to be a commandment specifically on how Jews should treat the poor within the ancient Land of Israel, but it is an enduring commandment among Jews to this very day. Giving tzedakah (charity) is a great virtue in Judaism and there are a large number of Jewish organization dedicated to providing for the needy, both among Jews and also the rest of the world. Christianity also has this value.

Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’

–Matthew 25:34-40 (ESV)

This great virtue of providing for the needy and suffering exists in modern Christianity. At every disaster, you will find Christian professionals and laypeople volunteering to render aid to the suffering by providing medical treatment and supplies, food, water, clothing, and other needs. There are Christian missions all over the world building churches, sheltering the persecuted, comforting the dying, and offering time, money, and material goods to anyone in need.

To love the stranger (Deut. 10:19)

Deuteronomy 10:19 in the Tanakh states:

You shall love the proselyte for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

Based on this translation and within its context, this specifically means that the native-born Israelite is to love the non-Israelite who has bound himself to the Laws of Hashem with the intent of having themselves and their descendents become full members of the community. Ultimately, the proselyte’s descendants (third generation and later) would fully assimilate and intermarry within Israel and history would “forget” whose ancestors were from among the proselytes and whose were from among the native-born Israelites.

Based on this translation and within its context, this specifically means that the native-born Israelite is to love the non-Israelite who has bound himself to the Laws of Hashem with the intent of having themselves and their descendents become full members of the community. Ultimately, the proselyte’s descendants (third generation and later) would fully assimilate and intermarry within Israel and history would “forget” whose ancestors were from among the proselytes and whose were from among the native-born Israelites.

Because “strangers,” “aliens,” or proselytes had no tribal affiliations, they could easily be victimized or treated as “second-class citizens” within Israel. God is commanding that they be loved by Israel in the memory of how Israel was treated as “strangers” (and slaves) in Egypt, not to replicate victimizing the stranger in the way that Israel was victimized in Egypt.

Today, this mitzvah is most commonly expressed in how Jews treat a Gentile who is in the process of converting or who has converted to Judaism. They are not to be treated differently within their community than the “native-born” Jew. This could, particularly within Reform synagogues, also be generalized to the Gentiles in their midst. There are a fair number of Jewish/Christian intermarried couples in Reform communities. At my own local Reform-Conservative shul, Gentiles even sit on the synagogue’s board of directors, so they are quite integrated into the Jewish community in that respect. A Gentile is still very unlikely to be called up for an aliyah to read the Torah on Shabbat or to lead the service when the Rabbi is unavailable, but in most other ways, they are equal in the community (perhaps this is the model for how non-Jews are treated in Messianic Jewish synagogues as well). This would be less true in Conservative Judaism and not even possible among the Orthodox, but even then, Gentiles who were intermarried to Jews in those communities would be treated (ideally) with respect and courtesy (and probably the best example of this is within Chabad synagogues).

This is a mitzvah that is looked at differently in Christianity since, by its very nature, no one is born a believer, even people who are born and raised in Christian families. We were all “strangers” to God and to Christianity at one point in our lives. Our duty is not to shun the non-believer but to welcome him and her into our midst in the name of the Christ who welcomed us.

OK, that was only three commandments out of 613, but it’s a nice start. We can see that in many important ways, how Jews and Christians obey God are identical or very similar. Know God. Give to the needy. Love the stranger among you. Both Christians and Jews do this. Identity is all but irrelevant in these cases. A Christian can as easily and as effectively give food to a hungry person as a Jew. You don’t have to bend yourself into an alternate identity to accomplish this. Really folks, it’s not rocket science.

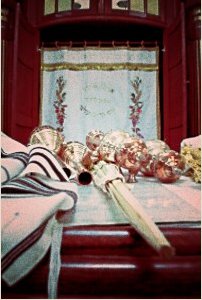

I suppose you noticed that the list includes a great many items that Christians don’t address, such as “To circumcise the male offspring (Gen. 17:12; Lev. 12:3)”, “To put tzitzit on the corners of clothing (Num. 15:38)”, “To bind tefillin on the head (Deut. 6:8)”, and so on. These are behaviors that are typically associated with Jewish identity. That is, you perform these commandments specifically because you are Jewish and anyone who performs them, whether it’s their intent or not, will very likely appear Jewish to anyone who sees them.

In certain small religious circles, the question of whether or not Christians should perform these mitzvot as an act of a disciple imitating their Rabbi and Master Jesus is an ongoing debate. For the vast majority of Christianity, obeying the mitzvot of feeding the hungry and visiting the sick seems much more substantial and possesses a greater quality of imitating Jesus than (purposefully or otherwise) appearing overtly Jewish. How you choose to obey God must be within your understanding of Scripture and as it exists within your conscience. However, don’t disregard the “weightier matters of the Law” for the sake of your perceived devotion to the more superficial signs. Filling a hungry five-year old’s tummy will always trump whether or not to lay tefillin during morning prayers, at least within my conscience.