Last week at the Western Wall, I asked an elderly man to put on tefillin. He strongly refused.

Last week at the Western Wall, I asked an elderly man to put on tefillin. He strongly refused.

I asked him, “When was the last time you put on tefillin?”

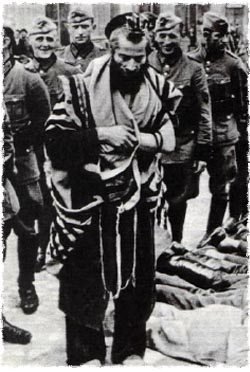

He smiled and proudly said, “72 years ago!” He held out his arm to show me the fading tattooed numbers. “1938,” he said. “It was the day of Kristallnacht. Do you know what Kristallnacht is?”

“Of course I do,” I told him.

“Two hundred and sixty-seven synagogues were burned down in one night. They burned down our synagogue, too. My tefillin were burnt up, and I have never put them on again,” he said.

“I have a friend who was in the camps, too,” I quickly said, “and he not only puts on tefillin today, but he even put them onto others inside the camp! Do you want to hear how he got tefillin into the camp?”

“Yes,” he said strongly. “How did he get them in there?”

-Gutman Locks

“Tefillin After 72 Years”

Stories of the Holocaust series

Chabad.org

I can’t even imagine what it would have been like to experience the horrors of the Holocaust. Like many Americans, I live a relatively comfortable life. I don’t really know what it’s like to go without adequate food, shelter, or clothing. I’ve been in the hospital before, but remain fairly healthy. I was once beaten by several men during a riot when I was 16 and spent some time recovering, but I was home and eventually after over a year, I began to let myself feel safe again. In short, I’ve faced a certain number of challenges over my lifetime, but none have been overly difficult.

I can’t even imagine what it would have been like to experience the horrors of the Holocaust.

I can’t even imagine what it would be like to have a wife who is struggling with cancer and who may die.

I can’t even imagine what it would be like to be the father of terminally ill child.

Frankly, I don’t want to imagine, let alone have to actually face such hideous tragedies in life. I don’t know how people do it and, I’m ashamed to say, I don’t even know how people of faith do it.

Where do you find hope in hopelessness? It’s one thing to say “I rely on my God for my strength,” and it’s another thing to actually live it out, one day at a time, one horrible, agonizing minute at a time. What can you do when someone delivers the terrible news and your courage melts like a plastic sandwich bag in the face of an inferno? What do you do when you’re a young, teenage boy and you and your mates are being herded into the gas chambers by the Nazis and you have only minutes to live?

Where do you find hope in hopelessness? It’s one thing to say “I rely on my God for my strength,” and it’s another thing to actually live it out, one day at a time, one horrible, agonizing minute at a time. What can you do when someone delivers the terrible news and your courage melts like a plastic sandwich bag in the face of an inferno? What do you do when you’re a young, teenage boy and you and your mates are being herded into the gas chambers by the Nazis and you have only minutes to live?

“He began his story. The Nazis had come to the ghetto and grabbed 137 young boys. He told me that only five of them survived. Only five.

“He was thirteen and a half years old. He was wearing the high boots that his father had bought him, and when he saw them coming, he stuffed his tefillin into one boot and his prayerbook in the other.

“They pushed the boys into a cattle car and drove them to the death camp, not far from the ghetto. When the train stopped, they slid open the side of the cattle car and immediately began pushing them toward the open door of the gas chamber. The boys were frightened and cried out. They asked Laibel, ‘What should we do?’ He told them, ‘We’re going to stand in rows five across, and we’re going to march right into that gas chamber singing a song of faith, the “Ani Maamin.”’ And they did just that. They stood in rows five across, and started singing and marching right into the chamber.

“The guards became so confused that they did not know what to do. They screamed, ‘You can’t do that! No one has ever done such a thing before. Stop it! Stop it at once! Here! Go over there to the showers instead!’

“They pushed them over to the showers, and forced them to undress and throw their clothing into a pile in the middle of the floor. They made them empty their shoes, and the tefillin and prayerbook fell out onto the pile.

“After the shower, when they were dressed in camp clothes and were being pushed out, past the pile of their clothes, Laibel saw his tefillin and prayerbook lying there. He wanted so badly to run and pick them up, but terrifying guards were watching. He said to the boys, ‘I did something for you, so now you do something for me.’

“‘Whatever you want,’ they said. ‘You saved our lives.’

“He said, ‘When I give the signal, start a fight and scream out loud. Okay . . . now!’ The boys started to fight and scream. The guards ran over and tried to pull them apart, but they wouldn’t stop fighting. In the confusion, he ran over and grabbed his tefillin and prayerbook, and hid them under his arms.

Laibel not only managed to retrieve his tefillin but he wore them (clandestinely) in the camp and helped other Jews wear them, too. In the story commemorating his courage, we discover him as an old man today helping men wear tefillin at the Kotel.

And he looked me in the eye and said, ‘And I put tefillin on other men, too.’ I started to cry, and I kissed him on his yarmulke.

“The day after Laibel told me his story, there was a soldier at the Western Wall who wouldn’t put on tefillin. No matter what I said, he simply refused. Then I told him Laibel’s story, and he quickly said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’

“And you can do it, too,” I said to the elderly gentleman who hadn’t donned tefillin in 72 years, as I gently slid the tefillin I was holding onto his arm. He said the blessing and started to cry. We said the Shema, and he prayed for his family. He began to smile even while the tears were streaming down his face. A crowd gathered around and congratulated him on overcoming all those years of rejection.

You do not always succeed, but you always have to try.

If there has ever been a hopeless place on earth, it was in the Nazi death camps during the Holocaust. Even those who were not immediately killed expected to die a lingering and torturous death. Even those who survived and who were liberated didn’t expect to live any sort of “normal” Jewish life again. Who could after seeing what they saw and experiencing what they lived through? Even after more than seven decades, Holocaust survivors are suffering delayed post-traumatic stress disorder. The statement is so obvious, it’s almost laughable to report it in the media. Of course they’re suffering after seventy years? Who wouldn’t?

But after over seventy years, some have turned suffering and hopelessness into hope, not just for themselves but for each other. Laibel turns hopelessness into hope every time he helps another Jewish man don tefillin and pray at the Kotel. A Jewish man who hadn’t worn tefillin in seventy-two years because of the nightmare of Kristallnacht put on tefillin again because of Laibel’s inspiration, “said the blessing and started to cry.”

While most of us have never faced such horrendous, nightmarish, ghastly experiences as those of Holocaust survivors, as those who are battling desperately invasive cancer, as those who are anxiously trying to comfort a dying child, we still know the world is filled with hopelessness and despair. All of us face some sort of problem, some sort of challenge, something that makes us want to give up our fight to move forward or maybe even the fight to live.

While most of us have never faced such horrendous, nightmarish, ghastly experiences as those of Holocaust survivors, as those who are battling desperately invasive cancer, as those who are anxiously trying to comfort a dying child, we still know the world is filled with hopelessness and despair. All of us face some sort of problem, some sort of challenge, something that makes us want to give up our fight to move forward or maybe even the fight to live.

I have no magic to give you. I have no secret formula with which you can overcome your hardships or worries or fears or tears. I can say “rely on God” but for even those men and women who do rely on Him with an almost superhuman faith and courage, the battle is hard and surrender to the darkness is a constant companion.

But amazingly there is still hope. Laibel must be well over eighty years old and for him, hope is helping just one more man put on tefillin, maybe for the first time in decades, and speak words of blessing to God. Hope is saying, “I love you” to a dying little boy. Hope is continuing to pray for your spouse, even though multiple organs are compromised by cancer and years of radiation and chemotherapy haven’t put the demon back in the bottle.

Hope is in the tears you cry. Hope is in your screams of anguish. Hope is being able to go on when life is impossible. Hope is a man learning how to pray again while crying after seventy-two years.

Hope is the faint light of a tiny candle holding the encroaching abyss at bay.

Hope is God.