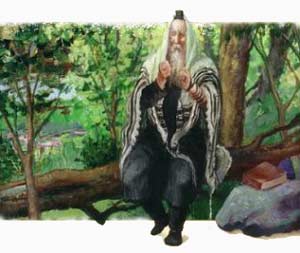

Jonah had gone out and sat down at a place east of the city. There he made himself a shelter, sat in its shade and waited to see what would happen to the city. Now the Lord G-d appointed a kikayon, and it grew up over Jonah to be shade over his head, to save him from his discomfort. Jonah was overjoyed with the kikayon.

Jonah had gone out and sat down at a place east of the city. There he made himself a shelter, sat in its shade and waited to see what would happen to the city. Now the Lord G-d appointed a kikayon, and it grew up over Jonah to be shade over his head, to save him from his discomfort. Jonah was overjoyed with the kikayon.

But G-d designated a worm when the morning rose the next day, and the worm attacked the kikayon, and it withered.

Now it came to pass when the sun shone, that G-d appointed a stifling east wind; the sun beat on Jonah’s head, and he felt faint. He begged to die, and he said, “It would be better for me to die than to live.”

And G-d said to Jonah: “Are you very grieved about the kikayon?” And he said, “I am very grieved even to the point of death.”

And the Lord said: “You took pity on the kikayon, for which you did not toil nor did you make it grow; it lived one night and the next night perished. Now should I not take pity on Nineveh, the great city, in which there are many more than one hundred twenty thousand people that cannot discern between their right hand and their left, and many animals as well?”–Jonah 4:5-11

Before continuing to read, if you haven’t done so already, go to yesterday’s meditation and review part 2 in this series: Mission Drift, then come back here.

The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute’s Rabbi Mordechai Dinerman wrote a commentary called “Jonah and the Big Shade” on which today’s morning meditation is based. You all probably know the basic story of Jonah. My inserting Jonah’s story here may seem a little mysterious in light of what I’m trying to study in this series of blog posts. Most people walk around the earth searching for purpose and meaning, but for Jonah, those things were abundantly clear. Right from the beginning, Jonah was a Prophet of God and his path was set before him:

The word of the LORD came to Jonah son of Amittai: “Go to the great city of Nineveh and preach against it, because its wickedness has come up before me.” –Jonah 1:1-2

I would imagine that if God came out point blank and told me the specifics of my purpose in life, where I was to go to find it, and what I was to do to fulfill it, I’d be thrilled beyond comprehension. But then again, maybe not. Jonah wasn’t thrilled. In fact, he tried to run away from his purpose and from God. He didn’t get very far. He was meant to go to Ninevah one way or the other. Like the old joke says, “we can do this the easy way or the hard way.” Jonah didn’t choose the easy way.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a blog post as a commentary for Torah Portion Masei. One of the key features of this Torah Portion is Moses reciting all of the places the Children of Israel camped during the 40 years of wandering. Why do that? Wasn’t the journey more important than the rest stops?

Perhaps not.

Recall the quote from yesterday’s morning meditation that was taken from the course book for the “Toward a Meaningful Life” lesson:

I wake up in the morning with the knowledge that my unique opportunities will be used to convey my individual personality in the places I find myself, thus inspiring the people around me.

Pay attention to the phrases, “my unique opportunities” and “in the places I find myself”. For Jonah, he could go no place on earth besides Nineveh in order to fulfill his purpose. He tried to go just about anyplace else, but that didn’t work out. Once the Children of Israel were consigned to wander the Sinai for 40 years, were they just wandering, or was there a purpose to where they went and what they did while they were there? What would have happened if they hadn’t encountered the descendents of Lot or Esau? Was it important that Aaron die specifically on Mount Hor? What about the battles and victories over Og, King of the Bashan and Sihon, King of the Amorites?

If the wanderings were truly aimless and the people and events they encountered really just random, why did Moses recount them to all of Israel on the threshold of entering Canaan? Why did Moses even bother to remember? Why were his words recorded in the Torah for all time to come, and why do we have them today?

Jonah had a reason to be at Ninevah and there was even a special purpose in his encounter with the kikayon plant (no one know exactly what this plant was supposed to be…it’s just a plant, but it had a purpose, too). Now think about where you go every day. Think about all of the places you’ve lived. Where have you gone on vacation? Where have you been “randomly” sidetracked? What did you do there and did any of it matter?

Jonah had a reason to be at Ninevah and there was even a special purpose in his encounter with the kikayon plant (no one know exactly what this plant was supposed to be…it’s just a plant, but it had a purpose, too). Now think about where you go every day. Think about all of the places you’ve lived. Where have you gone on vacation? Where have you been “randomly” sidetracked? What did you do there and did any of it matter?

If your life isn’t random and arbitrary but rather, has a purpose and meaning assigned by God, then so does where your feet have taken you, or your car, or a train, or a plane, or whatever transportation you have used.

But what about the kikayon? Why did Jonah care more about that plant than he did for over 120,000 people in one of the largest cities in the world (at that point in history)? For that matter, why did God care about Ninevah when they had sinned greatly, including against the Israelites? God has exterminated whole people groups for their sin. Why did he care enough to spare Ninevah?

The most common explanation is that He felt compassion for their lives. They didn’t know their left hand from their right. They were helpless and blind, as far as God was concerned. Did Jonah care about the kikayon in the same way that God cared for Ninevah?

Yes and no.

Rabbi Dinerman explains:

In fact, the final message of the Book of Jonah is much more than a message about compassion. It is a message about the utter indispensability of every creature. G-d allows Jonah to enjoy the shade of a simple plant that protects him from the blazing sun. And the relief that Jonah feels as a result is so great that he cannot imagine being deprived of it, and when it is taken away, he is so upset that he cannot imagine living without it.

Jonah wasn’t upset about the kikayon’s death because he had compassion for it. He was upset because the kikayon served the purpose of shading him from the elements, and its death ended that purpose in Jonah’s life. How does this apply to the people and animals of Ninevah? Did God spare them because they repented and He had pity on them, or did He spare them because they repented and they were ready to fulfill their purpose in life?

Wow!

Yesterday, I quoted Rabbi Simon Jacobson’s famous definition of purpose:

Birth is G-d’s way of saying “you matter.”

Perhaps life is G-d’s way of saying “you still matter.” As long as it lived, the kikayon had a purpose and when its purpose ended, God appointed the means of its death. Though Jonah fully expected to die when he was thrown into the sea, God appointed a sea creature to preserve his life and to deliver him to his destination. Although the Book of Jonah ends abruptly, as if stopping in the middle of the story, we know that God spared Ninevah for a reason, we just don’t know what happens next.

You and I are still alive today, but the rest of our story hasn’t been written yet. There are still places to go, people to meet, things to do, and somehow, that’s all part of the reason we are here, even if we don’t always understand it.

“And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you – you of little faith? –Matthew 6:28-30

The kikayon was only a plant, and yet it had a purpose assigned by the Creator of the Universe. Even the cattle in Ninevah each had a purpose. Jesus talks about grass growing one day and being thrown into the fire the next, and yet it is clothed in more splendor than King Solomon in all his royal glory.

Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground outside your Father’s care. And even the very hairs of your head are all numbered. So don’t be afraid; you are worth more than many sparrows. –Matthew 10:29-31

Grass, kikayons, sparrows, and cattle. Are you not worth more than all of these? If these common things all have a purpose and significance in the eyes of the Creator, how much greater is your purpose and significance to God?

Don’t go away. I’ll publish my commentary for Torah Portion Eikev in a few hours.

This series will continue on Sunday’s “morning meditation” Shattered Fragments. How does man and woman becoming “one flesh” affect the reason God made us?