Jewish wealth is not houses and gold. The everlasting Jewish wealth is: Being Jews who keep Torah and Mitzvot, and bringing into the world children and grandchildren who keep Torah and Mitzvot.

-from “Today’s Day” for Nissan 9 5703

Compiled and arranged by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, in 5703 (1943) from the talks and letters of the sixth Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory.

Chabad.org

“The older I get, the more I realize how different it is to be a Jew in a Jewish place as opposed to a Jew in a non-Jewish place. It’s definitely a different feeling in terms of how freely you can be yourself and celebrate your culture and religion.”

-Natalie Portman

I have tried to pull back from my formerly self-imposed obligation of writing and posting a “morning meditation” each day (except for Shabbos). I typically plan to write only one or two blog posts each week. But I realize that, perhaps below the level of conscious thought, I’m actually leaving room in my schedule for those things I write spontaneously when I come across a compelling topic…

…like Jewish identity.

Jewish identity and the approach of Pesach (Passover). What do they have in common besides the obvious?

Our Sages assert that the Israelites in Egypt were on the lowest level of spiritual impurity. They worshipped idols. They were debauched and dissolute. So how did they merit the grand and miraculous redemption?

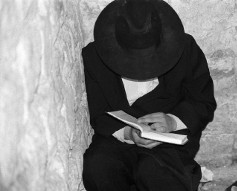

They had only three things going for them: They kept their Hebrew names, their Hebrew language, and their distinctive Hebrew dress. In other words, they retained their Jewish identity.

Wait a second! Didn’t you cringe when you found out that the biggest Ponzi scheme in history had been perpetuated by someone with a distinctly Jewish name? Wouldn’t we have preferred that instead of retaining his Jewish identity he had changed his name to Christopher Johnson?

What is the redemptive value of Jewish identity?

-Sara Yoheved Rigler

“Jewish Identity: Are You In or Out?”

Aish.com

In Christianity, one is redeemed by God due to faith in Jesus Christ. It’s not who we are, for Christ accepts everyone, regardless of heritage, background, nationality, language, walk of life, and so on. You aren’t saved by who you are but by what you believe, almost regardless of what you do about it (though to be fair, I know Christians who expect believers to live a transformed life in response to their faith).

But what Sara Yoheved Rigler is suggesting, is that Jews are redeemed by who they are, particularly in their outward appearance. What redeemed the ancient Israelites (according to the Sages) is that, regardless of worshiping idols and being enslaved, they retained an obvious Jewish identity.

Seems crazy, huh?

But according to Ms. Rigler, this isn’t just an issue for the Jews of antiquity, but it is a critical question for modern Judaism.

The question assumes particular importance in our generation. Indeed, the rates of adultery, domestic violence, addiction to drugs and porn, and murder for reasons as trifling as being cut off in traffic have skyrocketed in this generation. An objective look at our moral standing would produce a grim assessment.

Judaism promulgates a teleological worldview – that history is moving toward a specific goal, namely, the Redemption, or the Messianic era. So how can a generation as dissolute as ours be redeemed?

I’ve written before about the necessity of a Jewish community for Messianic Jews and that one of the critical purposes of Jewish community for Jews in Messiah is to prevent them from being cut off from the world-wide community of Jews. But no matter how much or how well I think I’ve made my point, it’s one that is difficult for many others, including some Messianic Jews, to accept.

I’ve written before about the necessity of a Jewish community for Messianic Jews and that one of the critical purposes of Jewish community for Jews in Messiah is to prevent them from being cut off from the world-wide community of Jews. But no matter how much or how well I think I’ve made my point, it’s one that is difficult for many others, including some Messianic Jews, to accept.

What many people read and hear is that I’m replacing Messiah with Judaism, as if Messiah and Judaism are mutually exclusive terms. Certainly the Chabad don’t think that, although they’d certainly disagree with me about the identity, function, and to a degree, purpose of the Messiah. On the other hand, they certainly expect him to arrive and don’t consider the desire for the coming of Messiah to eliminate their Jewish identity.

So where do we get the idea that Jews must stop being Jewish and stop having community with other Jews when they come to faith in Yeshua of Nazareth as Messiah?

From Christianity and Judaism, historically.

For nearly two-thousand years, any Jew who has realized that Jesus (Yeshua) is indeed the Messiah and desired to worship him and honor him has been required, by the Church (in its many and various forms) to renounce Jewish identity and Jewish practices and convert to (Gentile) Christianity. In its darkest days, the Church has resorted to various sanctions, torture, and even the threat of death to “convert” Jews to Christians. For Christianity, being Jewish and being a Christian are mutually exclusive terms.

To be fair, this is also considered true by most Jewish people. I’ve heard stories that in Orthodox Judaism, a friend or family member is mourned as if they died if they should become a Christian (I don’t know how true this is but I can see the point). Messianic Jews, that is, halachically Jewish people who come to faith in Yeshua as Messiah and yet retain their Jewish identity, continue to perform the mitzvot, and in all other ways, live a completely consistent Jewish life are still thought of as “Jews for Jesus” and tend to be shunned by secular and religious Jews alike.

In the Fall 2013 issue of Messiah Journal, Rabbi Stuart Dauermann wrote an impassioned plea that all Jews in Messiah must consider the Jewish people as Us, not Them, meaning that faith in Messiah should not and must not stand in between a Jew and all other Jews.

And many centuries ago, another Jew made a similar plea:

I am telling the truth in Christ, I am not lying, my conscience testifies with me in the Holy Spirit, that I have great sorrow and unceasing grief in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed, separated from Christ for the sake of my brethren, my kinsmen according to the flesh, who are Israelites, to whom belongs the adoption as sons, and the glory and the covenants and the giving of the Law and the temple service and the promises, whose are the fathers, and from whom is the Christ according to the flesh, who is over all, God blessed forever. Amen.

–Romans 9:1-5 (NASB)

In his faith in Messiah, Paul did not see himself as separated from the larger Jewish world or from other religious streams of Judaism. In fact, his love for his fellow (unbelieving) Jews was so great that he would have willingly become accursed and separated from the Messiah for the sake of other Jewish people, that they might see and accept Messiah as Paul did.

In his faith in Messiah, Paul did not see himself as separated from the larger Jewish world or from other religious streams of Judaism. In fact, his love for his fellow (unbelieving) Jews was so great that he would have willingly become accursed and separated from the Messiah for the sake of other Jewish people, that they might see and accept Messiah as Paul did.

For Paul, the Jewish people, all of them, were “us” not “them.” Jewish identity and faith in Messiah were never at odds for Paul. Faith in Messiah was the natural extension of his being a ”Hebrew of Hebrews; as to the Law, a Pharisee…as to the righteousness which is in the Law, found blameless” (Philippians 3:5-6). It’s thought by many Christians that Paul was talking about his past, before “conversion,” since he mentioned his persecuting the church, yet he was speaking in the present tense when he said:

I am a Jew, born in Tarsus of Cilicia, but brought up in this city, educated under Gamaliel, strictly according to the law of our fathers, being zealous for God just as you all are today.

–Acts 22:3 (NASB)

”Being zealous for God just as you all are today.” Paul was talking to a crowd of Jewish people. True, they were calling for his death, but that wasn’t because Paul surrendered his Jewish identity and was encouraging other Jews to do likewise, as the false allegations suggested. He remained a devout and faithful Jew and zealous for the Torah. His only “crime” was his fervent desire to also include Gentiles among the community of the redeemed.

Maimonides, in his code of Jewish Law, makes a startling pronouncement. He writes that a Jew who lives in isolation from the Jewish community, even if he keeps all the commandments, is considered a kofer b’ikar, a heretic. The implication is that identifying with the Jewish community is a basic value that underlies all the commandments.

Living among so many Gentiles for so much of his life must have taken a toll on Paul. I don’t know if the concept of kofer b’ikar existed in first century Judaism, but if it did, it may have been another reason the Jewish crowds in Acts 21-22 were so angry at Paul. He was a Jew who, because of his unique mission as an emissary to the Gentiles, didn’t spend a great deal of time in Jewish community. Yes, he went first to the Jew and then also to the Greek, but by the end of his third missionary journey, many Jewish communities in the diaspora were incensed with Paul because of the issue of the Gentiles.

This is a huge issue in Messianic Judaism today. This is one of the vital reasons why Messianic Jews must consider themselves as part of a larger Jewish community, not just a Messianic Jewish synagogue, but the overarching world of Jewry and affiliation and allegiance to national Israel. Even if a Messianic Jew is scrupulous in observing the Torah and faultless in performance of the mitzvot, outside of Jewish community, or more to the point, buried neck-deep in a community of Gentile believers, whether Messianic Gentiles or Evangelical Christians, the very real threat of kofer b’ikar and kareth exists.

I’m not suggesting that all Messianic Jews abandon their relationship with non-Jewish believers or stop associating with non-Jews in Messianic Jewish religious spaces, but first and foremost, a Messianic Jew must continually grasp tightly to the fact that he or she is a Jew and part of the Jewish people, all of them, everywhere.

In her article, Ms. Rigler goes on to describe the different critical points in history when Jews could and often did renounce their Jewish identity through forced or voluntary conversion to Christianity or to blend in with American culture when emigrating to this country.

That’s why alarm bells rang a couple years ago when a study revealed that 50% of American Jews under the age of 35 would not consider it “a personal tragedy if the State of Israel ceased to exist.” Two months ago an American Congresswoman declared that the Jews of America had sold out Israel in their support of Obama’s diplomatic surrender to Iran’s nuclear program.

Today, the community of Jews in the diaspora and particularly in western nations, could easily be extinguished through assimilation. I don’t believe that’s what God wants but I do believe it’s what most Christians want as long as said-assimilated Jews assimilated into the Church.

But unlike why I, or rather Ms. Rigler said above, it’s not just about appearing Jewish:

Let’s be clear here. God wants the maximum from us Jews: love your neighbor as yourself; keep Shabbos; don’t speak lashon hara; keep kosher – the whole nine yards. But the minimum requirement to be redeemed is to identify as a Jew.

Jewish identity is where you start, not where you finish. Particularly for Jews in Messiah, it must be abundantly clear to all other Jews as well as to everyone else, that the Jewish person in Messiah is Jewish. That’s why it’s (in my opinion) not optional for a Jew in Messiah to observe the mitzvot. While the minimum requirement to identify as a Jew is good, it is much better to go the whole nine yards, so to speak, and to live a life indistinguishable from other religious Jews, regardless if the standard of observance is Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform.

Jewish identity is what prompted Kirk Douglas to fast every Yom Kippur. As he proudly stated, “I might be making a film, but I fasted.”

Jewish identity is what prompted Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to post a large silver mezuzah on the doorpost of her Supreme Court chambers.

Jewish identity is what prompted movie star Scarlet Johansson to stand up for Israel at the cost of her prestige as an Oxfam ambassador.

This morning, Rabbi Michael Schiffman, who grew up in Jericho, NY in a traditional Jewish family, wrote a simple and heartwarming blog post called Finding Yeshua. No, being a Jewish believer and living a life consistent with Judaism, Jewish identity, and affiliation with Jewish community does not replace or reduce Messiah. It simply puts everything in perspective.

Ms. Rigler ends her article this way:

The Passover Seder speaks about four sons. Only one of them is cast as “wicked.” As the Hagaddah states: “The wicked son, what does he say? ‘What is this service to you?’ ‘To you,’ but not to him. Because he excludes himself from the community, he is a heretic. … Say to him, ‘Because of what God did for me when I went out of Egypt.’ For me, but not for him, because if he would have been there, he would not have been redeemed.”

The first Passover marked the birth of the Jewish nation. Every Passover since poses the challenge to every Jew: Are you in or are you out?

If you are Jewish and you are a believer, how do you answer this question? Since I’m not Jewish, it’s not a question directed at me, but as a Messianic Gentile, I believe it is my duty to encourage believing Jews to answer “in.”