The Jewish-Christian schism in Late Antiquity has been studied from numerous points of view. This paper will approach these events by investigating the manner in which halakhic issues (questions of Jewish law) motivated the approach of the early Rabbis to the rise of the new faith, and the manner in which Rabbinic legal enactments expressed that approach as well. The eventual conclusion of the Rabbis and the Jewish community that Christianity was a separate religion and that Christians were not Jews, was intimately bound up with the Jewish laws and traditions governing personal status in the Jewish community, both for Jews by birth and proselytes. These laws, as known today, were already in full effect by the rise of Christianity. In the eyes of the Rabbis, the evolution of Christianity from a group of Jews holding heretical beliefs into a group whose members lacked the legal status of Jewish identity and, hence, constituted a separate religious community, brought about further legal rulings which were intended to separate the Christians from the Jewish community.

The Jewish-Christian schism in Late Antiquity has been studied from numerous points of view. This paper will approach these events by investigating the manner in which halakhic issues (questions of Jewish law) motivated the approach of the early Rabbis to the rise of the new faith, and the manner in which Rabbinic legal enactments expressed that approach as well. The eventual conclusion of the Rabbis and the Jewish community that Christianity was a separate religion and that Christians were not Jews, was intimately bound up with the Jewish laws and traditions governing personal status in the Jewish community, both for Jews by birth and proselytes. These laws, as known today, were already in full effect by the rise of Christianity. In the eyes of the Rabbis, the evolution of Christianity from a group of Jews holding heretical beliefs into a group whose members lacked the legal status of Jewish identity and, hence, constituted a separate religious community, brought about further legal rulings which were intended to separate the Christians from the Jewish community.

-Prof. Lawrence H. Schiffman

“The Halakhic Response of the Rabbis to the Rise of Christianity”

lawrenceschiffman.com

Yahnatan Lasko at the Gathering Sparks blog sent me the link to Professor Schiffman’s brief article (and with a title like that, I was surprised it was so short) with the idea that I might want to write something in response (and I’m not the only blogger in the “Messianic space” Yahnatan notified). I emailed him back with my immediate thoughts:

Schiffman seems to be saying that prior to the destruction of the Temple, he believes that Jews who believed Yeshua was the Messiah and even Divine wouldn’t have caused any sort of rejection from the larger Jewish population or authority structures since there were multiple streams of Judaism in operation, with the general expectation that they were going to disagree with each other. The destruction of the Temple was the catalyst for many things, including Jewish dispersal, the apprehension of Gentile leadership of “the Way” for the first time, the power surge of Gentiles entering that Judaism, all resulting in the shift from Messiah worship as a Jewish religion to Christ worship as a Gentile faith. As Schiffman said, the Pharisees were the only Jewish stream to remain intact after the Temple’s fall and while “the Way” also survived, it took a divergent trajectory, leading it away from Judaism, so by default, the Pharisees became the foundation for later Rabbinic Judaism.

Schiffman is being very “gentle” in his treatment of this topic. I can see a blog post coming out of this in the semi-near future. Thanks for sending the link.

Of course, Schiffman also said that Jews who had faith in Yeshua (Jesus) as Messiah were holding “heretical beliefs,” so I guess he wasn’t all that gentle, but he still seems to be treating the topic with a lighter touch than you’d expect.

I was somewhat reminded of Talmudic scholar Daniel Boyarin’s treatment of “the story of Jesus Christ” in his book The Jewish Gospels (a book I extensively reviewed in The Unmixing Bowl, The Son of Man – The Son of God, and Jesus the Traditionalist Jew).

Boyarin, of course, didn’t express personal faith in Yeshua as Messiah or assign any credibility, from his perspective, that modern Judaism could consider Jesus as Moshiach, but he is another Jewish voice saying that, given the understanding of the Torah and the Prophets in the late Second Temple period, it was certainly reasonable and credible to expect that some Jews, perhaps a large number of Jews, would have accepted Yeshua’s Messianic claim and even his Divinity.

Today, for the vast majority of Jewish people, such thoughts are outrageous and offensive, but unwinding Jewish history and the development of Rabbinic thought back nearly twenty centuries, we encounter a different set of Judaisms than we observe in the modern era. We can’t really retrofit modern Jewish perspectives into the time of Jesus, Peter, and James anymore than the modern Church can insert post-Reformation and post-modern Christian theology and doctrine backward in time and into the original intent of the Gospel and Epistle writers, particularly Paul. Both inject massive doses of anachronism into the ancient Jewish streams of life when the Temple still stood in Jerusalem.

Today, for the vast majority of Jewish people, such thoughts are outrageous and offensive, but unwinding Jewish history and the development of Rabbinic thought back nearly twenty centuries, we encounter a different set of Judaisms than we observe in the modern era. We can’t really retrofit modern Jewish perspectives into the time of Jesus, Peter, and James anymore than the modern Church can insert post-Reformation and post-modern Christian theology and doctrine backward in time and into the original intent of the Gospel and Epistle writers, particularly Paul. Both inject massive doses of anachronism into the ancient Jewish streams of life when the Temple still stood in Jerusalem.

Today, it takes a tremendous amount of courage for any Jewish person, under any set of circumstances, to say anything even mildly complementary about the ancient Jewish stream of “the Way” and that it might be reasonable to believe that in that cultural and chronological context, Jewish people, from fishermen to scribes, might see the Messiah looking at them from the eyes of Jesus.

While our sources point to general adherence to Jewish law and practice by the earliest Christians, we must also remember that some deviation from the norms of the tannaim must have occurred already at the earliest period. Indeed, the sayings attributed by the Gospels to Jesus would lead us to believe that he may have taken a view of the halakhah that was different from that of the Pharisees,. Nonetheless, from the point of view of the halakhic standards, the early Rabbis did not see the earliest Christians as constituting a separate religious community.

-Schiffman

A number of months ago, Rabbi Dr. Carl Kinbar made a statement that I think speaks to the above-quoted comment of Professor Schiffman:

But, to complicate matters, different social groups and congregations often have their own versions of Torah that they enforce in these ways. Obviously, this situation is far from ideal.

Fortunately, God is (in my considered opinion) not a perfectionist. Even as he calls us to holiness, he understands the limitations that surround us. For the most part, then, Torah observance is essentially voluntary and variable rather than compulsory and uniform. In fact, this is exactly the situation that existed in Yeshua’s, when the vast majority of synagogues were “unaffiliated” and most Jews practiced what has been called “common Judaism.” In common Judaism, Jews kept the basics of Torah observance according to their customs but did not acknowledge the authority of the sects (including the Pharisees) to impose additional laws.

My understanding of what Rabbi Kinbar said was that while there was a basic or core set of standards and halachah that defined Judaism as an overarching identity and practice, not only were there multiple streams of Judaism (Pharisees, Essences, and so on), but significant variations of how Torah observance was defined among “different social groups and congregations” (and I apologize to Rabbi Kinbar in advance if I’ve misunderstood anything he’s said).

My understanding of what Rabbi Kinbar said was that while there was a basic or core set of standards and halachah that defined Judaism as an overarching identity and practice, not only were there multiple streams of Judaism (Pharisees, Essences, and so on), but significant variations of how Torah observance was defined among “different social groups and congregations” (and I apologize to Rabbi Kinbar in advance if I’ve misunderstood anything he’s said).

What this means for us as we’re gazing into the time of the apostles, is that there were many different expressions of what we call “Judaism” back in the day, but in spite of all the distinctions, including one group who paid homage to a lowly Jewish teacher from the Galilee as the Messiah and Divine Son of God, they were all accepted as Jewish people practicing valid Judaisms.

This situation changed with the destruction of the Temple. Divisions within the people, after all, had made the orderly prosecution of the war against the Romans and the defense of the Holy City impossible. The Temple had fallen as a result. Only in unity could the people and the land be rebuilt. It was only a question of which of the sects would unify the populace.

-Schiffman

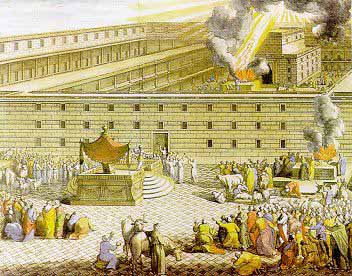

Holding all of this diversity together in a Jewish land occupied by the Roman empire was difficult enough, and more so for Jewish communities in the diaspora, but the Temple was the common denominator (even if you lived so far away that you could only afford to make the pilgrimage rarely) that defined all Jewish people everywhere. The Temple was always the center, the resting place of the Divine Presence, the only place on earth where once a year atonement was made for all of Israel.

And then it was gone.

As Schiffman points out, with their power base destroyed, the Sadducees where scattered to the winds. It could be argued that the Way, the ancient movement of Messiah worshipers, was a Pharisaic extension. We have indications that the apostle Paul not only did not abandon Jewish practice but remained Pharisaic throughout his life. Many of Yeshua’s teachings most closely fit the theology of the Pharisees. Even my Pastor said that if we lived in ancient Israel (and we were Jewish), we’d be Pharisees, because they were the “fundamentalists” of their day, the populist movement among the common Jewish people, Am Yisrael.

But the split would inevitably occur, perhaps not so much because one splinter group among the Pharisees, the Way, believed they had identified a Divine Messiah, but because a mass movement of Gentiles was entering that particular Jewish sect and, by definition, re-writing the nature of the movement as the majority Gentile membership achieved ascendency and as the Jewish membership were forced into exile, grieving a Temple and a Jerusalem left in ruins.

Of the vast numbers of Greco-Roman non-Jews who were attracted to Christianity, only a small number ever became proselytes to Judaism. The new Christianity was primarily Gentile, for it did not require its adherents to become circumcised and convert to Judaism or to observe the Law. Yet at the same time, Christianity in the Holy Land was still strongly Jewish.

As the destruction of the Temple was nearing, the differences between Judaism and Christianity were widening. By the time the Temple was destroyed, the Jewish Christians were a minority among the total number of Christians, and it was becoming clear that the future of the new religion would be dominated by Gentile Christians. Nevertheless, the tannaim still came into contact primarily with Jewish Christians and so continued to regard the Christians as Jews who had gone astray by following the teachings of Jesus.

-Schiffman

According to Schiffman’s commentary, as long as the “Christian” movement was largely controlled by Jews, it was a Judaism and Jewish people who believed that a Jewish Rabbi was actually the Messiah were still Jewish. In fact, in that time and place, it was probably a no-brainer. No one would have even questioned that any Jewish adherent to the Way wasn’t Jewish, anymore than any Jewish person today would question the “Jewishness” of a Chabad adherent believing their beloved Rebbe will one day be resurrected as the Messiah.

According to Schiffman’s commentary, as long as the “Christian” movement was largely controlled by Jews, it was a Judaism and Jewish people who believed that a Jewish Rabbi was actually the Messiah were still Jewish. In fact, in that time and place, it was probably a no-brainer. No one would have even questioned that any Jewish adherent to the Way wasn’t Jewish, anymore than any Jewish person today would question the “Jewishness” of a Chabad adherent believing their beloved Rebbe will one day be resurrected as the Messiah.

Schiffman said that other Jewish streams would have considered Jewish Yeshua-believers as misguided but Jewish, much as other Jewish streams might consider the Chabad and their attitude about the Rebbe today.

If today’s Jewish people (or for that matter, today’s Christians) could look through that long telescope back to the world of Peter, James, and Paul, they might gain a vision that would help them see what I see in today’s Messianic Jewish movement; a perspective that illuminates the “Jewishness” of those men and women who are observant Jews and who have put their hope in the Messiah, who once walked among his people Israel as a teacher from the Galilee who went about gathering disciples, and ended up revolutionizing the world.