I was thinking about the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32) while driving in to work this morning (Friday) and in relation to the stream of repentance, atonement, and forgiveness related blog posts I’ve been writing lately. The parable is only twenty-two verses long, just a couple of paragraphs, but if it were a true to life experience, the events being described could have taken months or even years.

A selfish son demanded of his father his inheritance, which one usually doesn’t receive until the father dies. This was a rather cold-blooded thing to ask for, but his father relented. This son, the younger of two brothers, did what most young people would do with a lot of money they didn’t have to earn by working. He blew it all on what the NASB translation calls “loose living” and ended up impoverished, that is, flat broke. All that money, presumably a sizable sum, and it’s all gone.

So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, and he sent him into his fields to feed swine. And he would have gladly filled his stomach with the pods that the swine were eating, and no one was giving anything to him. But when he came to his senses, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired men have more than enough bread, but I am dying here with hunger! I will get up and go to my father, and will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in your sight; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me as one of your hired men.”’

–Luke 15:15-19

Like I said, it could have taken this young person months or even years to reach this dead-end in his life. What was he doing in the meantime? Apparently enjoying himself. Until the money ran out, he probably didn’t give a second thought to the cruel way he had treated his father and how he had deserted his family in pursuit of his own pleasure and enjoyment.

Once he ended up broke, we don’t really have a sense of how long he was working as a hired laborer, but if he wasn’t eating even as well as the pigs he fed, it probably wasn’t too long. Assuming he was just really hungry and not literally starving, it would have still been weeks or months before he hit that hard wall and finally overcame his pride, self-indulgence, and then shame and fear at the thought of turning back to his father.

Shame and fear?

Sure.

Look at what he did. He pretty much demanded his father (virtually) die so this kid could have whatever he would have inherited of his father’s estate upon Dad’s death. I doubt the guy was ever planning to see or speak to his father again, so after throwing the supreme insult in his Dad’s face, what was it like to even imagine being confronted by his father again? By rights, Dad should have told him to get lost and slammed the door in his face, leaving this boy homeless, abandoned, and alone. What a tremendous risk it would be, emotionally and physically, for him to walk back home and to ask to be treated, not as a son, but as a hired hand.

However, as we see in the parable, the kid had gotten to the point where he had nothing to lose. He was starving anyway. The pigs got fed but no one was giving him any food. Why not take the chance? Who knows? Maybe his father would have pity on him and at least give him a job in the fields or tending the sheep.

I was also thinking about the story of Joseph. It’s not until Parasha Va-yiggash (Genesis 44:18-47:27) when Jacob and his family descend into Egypt and Joseph is reunited with his father. Of course, ever since being sold into slavery in Egypt, Joseph’s behavior was exemplary, first as a slave in Potiphar’s household, and then as a prisoner in the King’s prison. His wrongdoing (in spite of how the Rabbinic sages seem to explain it away) ended when his brothers threw him into a pit with the intention of killing him. Teenage arrogance was tempered by trial and suffering which ultimately turned his talents toward saving the world from famine.

I was also thinking about the story of Joseph. It’s not until Parasha Va-yiggash (Genesis 44:18-47:27) when Jacob and his family descend into Egypt and Joseph is reunited with his father. Of course, ever since being sold into slavery in Egypt, Joseph’s behavior was exemplary, first as a slave in Potiphar’s household, and then as a prisoner in the King’s prison. His wrongdoing (in spite of how the Rabbinic sages seem to explain it away) ended when his brothers threw him into a pit with the intention of killing him. Teenage arrogance was tempered by trial and suffering which ultimately turned his talents toward saving the world from famine.

But I wonder if there’s a secondary lesson in all this? Both Jacob and Joseph suffered from their long separation. Jacob thought Joseph dead for long decades, while his brothers suffered the guilt and shame of knowing they had contributed to their favored sibling’s disappearance, and then lied about it to their father. They too suffered and Joseph in testing them, delivered stern consequences upon them until they admitted their wrongdoing.

Can Joseph, certainly a Messiah-like figure, be compared to the prodigal son? Was there a lesson he had to learn before he merited reunification with his family? It seems more likely that the brothers were the prodigals and it was what they needed to learn before being reunited with Joseph and being given the relative comforts the land of Goshen had to offer.

But consider:

He had sent Judah ahead of him to Joseph, to point the way before him to Goshen. So when they came to the region of Goshen, Joseph ordered his chariot and went to Goshen to meet his father Israel; he presented himself to him and, embracing him around the neck, he wept on his neck a good while. Then Israel said to Joseph, “Now I can die, having seen for myself that you are still alive.”

–Genesis 46:28-30 (JPS Tanakh)

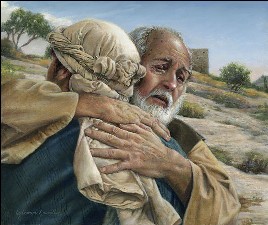

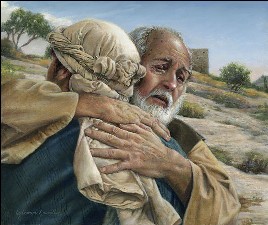

So he got up and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion for him, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and in your sight; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ But the father said to his slaves, ‘Quickly bring out the best robe and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand and sandals on his feet; and bring the fattened calf, kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.’ And they began to celebrate.

–Luke 15:20-24 (NASB)

Admittedly, except for the tearful reunion between father and son, there isn’t much of a comparison. Joseph is a Prince in Egypt, the most powerful man on Earth, except for Pharaoh King of Egypt, and Pharaoh denies Joseph nothing. Jacob and his family are saved from famine by going down to Egypt and accepting Pharaoh’s generosity (admittedly for the sake of Joseph who had saved Egypt). Conversely, it is the returning prodigal son who is saved by his father’s generosity, mercy, and joy.

But in all the years Joseph had been in Egypt, not once did he send a message to his grieving father that he was alive and well, even if he couldn’t tell him the exact circumstances for his long absence. Certainly a man of Joseph’s means could have sent a secret messenger into Canaan to let Jacob know he was alive. In this, he was like Jacob himself who, upon returning to Canaan with his family after serving Laban for twenty years and then escaping association with Esau, never let Isaac and Rebecca, who were both still alive at the time, know that he had returned. In fact, the only mention of Jacob and Isaac being together again was when Jacob and Esau buried their father upon his death (Genesis 35:28-29).

But in all the years Joseph had been in Egypt, not once did he send a message to his grieving father that he was alive and well, even if he couldn’t tell him the exact circumstances for his long absence. Certainly a man of Joseph’s means could have sent a secret messenger into Canaan to let Jacob know he was alive. In this, he was like Jacob himself who, upon returning to Canaan with his family after serving Laban for twenty years and then escaping association with Esau, never let Isaac and Rebecca, who were both still alive at the time, know that he had returned. In fact, the only mention of Jacob and Isaac being together again was when Jacob and Esau buried their father upon his death (Genesis 35:28-29).

At least the prodigal son didn’t wait that long. He returned to his father while Dad was still alive. For all Joseph knew, his father could have already died, which is why he urged his brothers, when they still didn’t know who Joseph was, to tell him about Jacob and Benjamin (Genesis 45:3 for example).

There are many things that we should do, but we procrastinate. We delay taking action. Doing nothing is often much easier then taking action. What can you say to get yourself moving? You can say, “Just do it.”

Sometimes we really have a good reason or reasons for hesitating. Deep down we may feel that it’s better for us not to take the action we’re postponing. But we aren’t yet clear about the entire matter. If you have an intuitive feeling that it might be unwise to take action, then wait. Think it over some more. Consult others.

But when you know that you or others will benefit if you take action and you don’t have a valid reason for procrastinating, tell yourself, “Just do it.”

(from Rabbi Zelig Pliskin’s book: “Conversations With Yourself”, p.141) [Artscroll.com])

-Rabbi Zelig Pliskin

from Daily Lift #192 “Just Do It

Aish.com

Hillel says, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? But if I am only for myself, who am I? If not now, when?”

-Ethics of the Fathers, 1:14

How long did it take for Joseph to call his father, brothers, and family to come and join him in the safety of Egypt during a world-wide famine? How long did it take for the prodigal son to hit rock bottom and in humiliation, return to his father?

Years. Decades.

How long will it take you and how long will it take me to finally return to our Father? What holds us back, the comfort and pleasure of the still wealthy prodigal? The power and control of Joseph, Prince of Egypt? Or the humiliation, shame, and fear of the dead broke prodigal son?

A single, impulsive act of disobedience is one thing and we can quickly apply correction and immediately repent and return. A lifetime of separation and self-indulgence isn’t swept aside so easily, and it can take time to reach the final conclusion that we have nothing left to lose and everything to gain if we turn around and go back where we came from. Even Joseph, who had every material comfort in the world, was still missing something without his family, for as a Hebrew, he was still utterly alone without his community, without his family, a servant of God amid a nation of pagans. That too is a habit difficult to break. Not that Joseph worshiped idols, but what about his wife and children? Maybe they didn’t either, but what about his in-laws? What about Pharaoh?

A single, impulsive act of disobedience is one thing and we can quickly apply correction and immediately repent and return. A lifetime of separation and self-indulgence isn’t swept aside so easily, and it can take time to reach the final conclusion that we have nothing left to lose and everything to gain if we turn around and go back where we came from. Even Joseph, who had every material comfort in the world, was still missing something without his family, for as a Hebrew, he was still utterly alone without his community, without his family, a servant of God amid a nation of pagans. That too is a habit difficult to break. Not that Joseph worshiped idols, but what about his wife and children? Maybe they didn’t either, but what about his in-laws? What about Pharaoh?

It took a long time before both of these men finally came to the point where they had to return to their families and become part of their community again.

Consider three things, and you will not approach sin. Know whence you came, whereto you are going, and before Whom you are destined to give an accounting.

-Ethics of the Fathers, 3:1

If we all considered these three statements with the proper gravity, we would be far less likely to sin and then keep on sinning (or sin, repent, sin, repent, sin…). But having reached a point to where you and I desire to return, these three things are dauntingly inhibiting, like staring up the summit of some great mountain that we realize we need to climb.

And being daunted and inhibited, we hesitate. Why now? Why not in a little bit? But then Hillel’s words come back to haunt us: “If not now, when?”

My rabbi once told me that even when I don’t feel like praying, I should still make an effort. Even if I feel completely disconnected from the action that I’m doing. Why? Because there will come a day when I will feel like praying, and if I haven’t been keeping my muscles in shape, I won’t be able to connect to my Creator through the vehicle of prayer. It will be so foreign to me that it will impede my attempt to connect.

By going through the motions, even in times of spiritual famine, I am keeping the lines of communication clear. I’m weeding my spiritual garden, even though I may not be harvesting any vegetables at the time.

-Rivki Silver

“Just Do It”

Aish.com

The practice of Judaism really is a matter of practice. Judaism isn’t so much a matter of believing as doing. As Ms. Silver tells us in her brief article, a relationship with God is something you perform, saying the blessings and doing the mitzvot, even when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you don’t practice at all or at least not as much as needed.

The practice of Judaism really is a matter of practice. Judaism isn’t so much a matter of believing as doing. As Ms. Silver tells us in her brief article, a relationship with God is something you perform, saying the blessings and doing the mitzvot, even when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you don’t practice at all or at least not as much as needed.

Judaism is very much a religion of practice, of doing. In the morning, I wake up and thank God for creating me and giving me another day. Then I ritually wash my hands. If I’m really on it, I’ll say my morning blessings after that (though sometimes they get said a little later).

When you do something every day, it becomes routine. And then something which is really quite sublime can become rote. And then the emotional component of spirituality which is, for many people, a big draw, can become separated from the physical component of spirituality. And then you can wake up one morning and realize that you’re just going through the motions.

I know. I’ve been there. I AM there in some areas of my practice.

Time to give up? Not so fast.

As the previous quote from Ms. Silver states, even “going through the motions” serves as a sort of “place holder” until we are ready to stop being “spiritual zombies”. Speaking of which:

This doesn’t mean that it’s okay to stay a spiritual zombie. While the reality of my morning blessings may be that I don’t have the best concentration while saying them, that doesn’t exempt me from trying to improve their quality.

We’re not perfect, and that’s okay. When Jascha Heifetz first picked up a violin, he wasn’t perfect either. It took years of practice and determination to become great.

And that’s something I find encouraging when I’m not feeling particularly “spiritual,” when doing a mitzvah might even feel like one more thing to check off my to-do list. I know that by continuing to practice, I am continually improving, much like a musician who is working on a piece of music.

Have you ever considered that true repentance takes time and practice as well? I’ve always imagined repentance to occur in an instant. Just repent of your sins to God, change your behavior, and it’s all done.

Well, no. I think that’s why so many people trying to break a long pattern of sinful behavior have such a difficult time. If you expect repentance, atonement, and forgiveness in an instant and it doesn’t actually happen in an instant, it’s demoralizing. Imagine thinking you’ve repented only to give in to the temptation to return to sin. It’s a horrible thing. What if it means repentance doesn’t work? You’re trapped.

Time to give up? Not so fast.

The “just do it” slogan made famous by Nike, doesn’t always mean do it once, do it right, and do it permanently. I’m not excusing the revolving door method of sin, repentance, sin, and so on. I’m saying that what has taken years to build up won’t always get torn down in a single day. Ever watch an old building being demolished? Sure, it doesn’t take as long to knock it down as it took to construct it, but it still takes time. Further, it takes planning, the right equipment, and the right execution. So too repentance.

The journey from the pig farm in a foreign country to home must have taken some time, even after the prodigal son made his decision. So too with us. Maybe his trip was uneventful or maybe there were barriers along the way that Jesus (Yeshua) didn’t include in his parable. They probably weren’t relevant to the point the Master was making, but maybe they’re relevant to us.

The journey from the pig farm in a foreign country to home must have taken some time, even after the prodigal son made his decision. So too with us. Maybe his trip was uneventful or maybe there were barriers along the way that Jesus (Yeshua) didn’t include in his parable. They probably weren’t relevant to the point the Master was making, but maybe they’re relevant to us.

Repentance takes practice, like a Jewish person trying to overcome being “stuck” on a particular mitzvah. But it’s like a young child learning how to walk. The would-be toddler never gives up and decides to keep crawling for the rest of his or her life. They keep at it. They’re driven to learn to walk and eventually they do. The child’s parents don’t give up on the little one for standing and falling and standing and falling and taking a step and falling. As long as the child keeps trying, there’s nothing to be concerned about and most parents are pretty patient with the whole process.

How much more so is our Heavenly Father patient with us…

…as long as we keep trying and practicing and we don’t give up.

I’m reminded of Toby Janicki’s blog post of four years ago called The Scoop on What About Paganism, a topic he expanded upon greatly in his lecture series “What About Paganism” (available on Audio CD and in MP3 format). Toby coined the term “paganoia” in his lectures, and I think the term is fitting.

I’m reminded of Toby Janicki’s blog post of four years ago called The Scoop on What About Paganism, a topic he expanded upon greatly in his lecture series “What About Paganism” (available on Audio CD and in MP3 format). Toby coined the term “paganoia” in his lectures, and I think the term is fitting.