When I started writing this missive, I thought the answer had all to do with the Apostle Paul. By the time I finished, I realized I was dead wrong.

Let me explain.

This issue is compounded by two additional assumptions, based on the New Testament book of Romans – written by Paul whose authority is questionable because he never met Jesus.

-Rabbi Bentzion Kravitz

“Know How to Answer Christian Missionaries”

Aish.com

Articles like this make my heart ache because they are based on the assumption that everyone who has received and accepted the revelation that Rav Yeshua (Jesus) is the Messiah has an understanding of Jesus that’s exactly the same as Evangelical Christian theology and doctrine.

This is not consistent with many Messianic Jews I’ve met, either in person or over the web. In fact, most of those Jews have more in common with people like Rabbi Kravitz than they do with me.

But I’m not writing this to convince any Jewish person (or Gentile Noahide for that matter) of the validity of Yeshua’s identity and role, past, present, or future.

My current investigation has to do with a Gentile establishing and maintaining a relationship with Hashem outside traditional Christianity and Messianic Jewish community. For the former, this is the case because I’m definitely not a good fit for the Church, and for the latter, because I suspect any involvement on my part in either Christianity or the Messianic movement just drives my (non-Messianic) Jewish wife nuts.

Not that it’s her fault. That’s just the way it is. She’d probably get along famously with the above-quoted Rabbi Kravitz and eat up his responses to missionaries with a spoon.

So given my circumstances, and the circumstances of quite a number of “Judaicly aware” non-Jews who for many different reasons can’t or won’t join in a community, we turn back to the Bible and to God as our only resources.

I was trying to find a condensed list of the various directives that Paul issued to his non-Jewish disciples so I could “cut to the chase,” so to speak, but doing that search online is proving difficult. I keep encountering traditional interpretations of Paul as having done away with the Law and having replaced it with grace and so on.

I could turn to more “Messianic” or “Jewish” friendly commentaries, but many or most of them are quite scholarly and beyond my limited intellectual and educational abilities and experience.

I do point the reader to a source I’ve mentioned quite a bit of late, the Mark Nanos and Magnus Zetterholm volume Paul within Judaism: Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle. This is a collection of articles written by various researchers who are part of the “new perspective on Paul” movement, those who have chosen to reject the traditional interpretation of the apostle and who have taken a fresh look at his life and writings within the context of first century Judaism.

You get a really different opinion of Paul when you take off your Christian blinders (sorry if that sounds a tad harsh).

You get a really different opinion of Paul when you take off your Christian blinders (sorry if that sounds a tad harsh).

I did look up Paul at beliefnet.com and they do seem to state that Paul was Jewish, but unfortunately, they take a more or less traditional point of view on what the apostle taught.

They did say that of all the epistles we have recorded in the Apostolic Scriptures, scholars are sure he was actually the author of:

- 1 Thessalonians

- Galatians

- 1 & 2 Corinthians

- Philippians

- Philemon

- Romans

Even limiting my investigation to those letters, I’m still faced with a lot of challenges. Romans alone is worth a book, actually many books, and is so complex I doubt I’d ever do more than scratch the surface of its meaning.

But maybe I don’t have to start from scratch. After all, in the several years I’m maintained this blogspot, I’ve written many times on Paul. Maybe I don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Perhaps all I have to do is read what I’ve already written.

Searching “Paul” on my own blog renders 33 pages of search results but I need to narrow it down more to what Rav Shaul specifically said about the Gentiles.

Actually, only the first two pages contain blog posts specifically with “Paul” in the title. It gets a little more generalized after that.

The added problem is typically, any time I wrote about Paul and the Gentile, it was usually in relation to or contrasting the role of Messianic Jew and Judaicly aware Gentile. I produced very little, if anything, about Gentiles as Gentiles. After all, I’ve been a champion (minor league, of course) of the cause of Messianic Jews to be considered Jewish and operating within a Judaism, just the same as other observant Jews in various other religious Jewish streams.

Only of late have I found it necessary to advocate for the Gentiles, and more specifically, me. Only recently have I realized that while it’s a good thing to emphasize Judaism for the Messianic Jew, it has some serious drawbacks for the so-called “Messianic Gentile,” not the least of which is resulting in some non-Jewish believers losing their identity because they’re surrounded by all things Jewish, including siddurim, kippot, Torah services, and tallit gadolim.

While I still believe that a significant role of the Judaicly aware Gentile as well as the more “standard” Christian is in support of Israel and the Jewish people, just as Paul required of his Gentile disciples in ancient times, I also believe there has to be something more for us to hang onto.

Or to borrow and adapt a hashtag from recent social media outbursts, #GentileLivesMatter (by the way, using Google image search to look up “goy” or “goyishe” returns some pretty anti-Semitic graphics).

I did find a blog post I wrote in January 2014 called The Consequences of Gentile Identity in Messiah, but I’m not sure how useful it is in my current quest, in part because I wrote:

I did find a blog post I wrote in January 2014 called The Consequences of Gentile Identity in Messiah, but I’m not sure how useful it is in my current quest, in part because I wrote:

I wrote a number of detailed reviews of the Nanos book The Mystery of Romans including this one that described a sort of mutual dependency Paul characterized between the believing Gentiles and believing and non-believing Jews in Rome.

You can go to the original blog post to click on the links I embedded into that paragraph, but if part of who we non-Jews are is mutually dependent on Jews in Messiah, that leaves me pretty much up the creek without a paddle.

Of course, that’s citing Nanos and his classic commentary The Mystery of Romans, which describes a rather particular and even unique social context, so there may be more than one way to be a Judaicly aware Gentile and relate to God.

The problem then is how to take all this “Judaic awareness” and manage to pull a Gentile identity out of it that doesn’t depend on (Messianic) Jewish community. Actually, I would think this would be as much a priority for Messianic Jews as it is for me, especially when, as I’ve said in the past, in order for Messianic Jewish community to survive let alone thrive, Messianic Jewish community must be by and for Jews.

To put it another way quoting Rabbi Kravitz’s lengthy article:

The growth of Christian support for Israel has created an illusion that we have nothing to worry about because “they are our best friends.”

It would be a mistake to think the risk has been minimized, especially to Jewish students and young adults, just because missionaries are less visible on street corners and offer much appreciated Christian support for Israel.

Granted, R. Kravitz must paint the Church in the role of adversary if he believes that Christians are dedicated to missionizing young Jews so that they’ll abandon Jewish identity and convert to Goyishe Christianity, but we non-Jews in Messianic Jewish community are also sometimes cast as a danger in said-community because our very presence requires some “watering down” of Jewish praxis and Jewish interaction.

I suspect the same was true in Paul’s day and ultimately, it was this dissonance that resulted in a rather ugly divorce between ancient Jewish and Gentile disciples of Messiah.

Gentiles resolved the conflict by inventing a new religion: Christianity, and they kicked the Jews out of their own party, so to speak, by refactoring everything Jesus and Paul wrote as anti-Torah, anti-Temple, and anti-Judaism.

That does me no good because I don’t believe all that stuff, that is, I’m not an Evangelical Christian. I need an identity that allows for my current perspective, my pro-centrality of Israel and Torah for the Jews perspective, my King Messiah is the King of Israel and will reign over all the nations from Jerusalem in Messianic Days perspective, and still lets me be me, or the “me” I will be in those days, Hashem be willing.

Think about it.

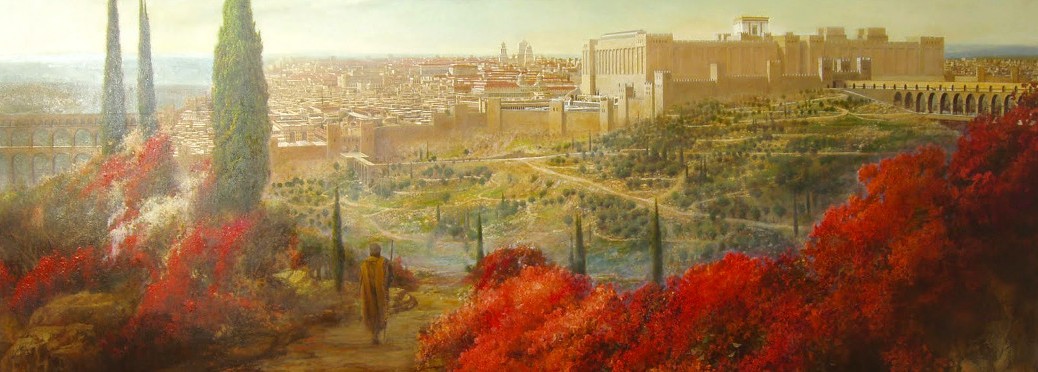

All Jewish people will live in Israel. It will once again be a totally Jewish nation. As far as I can tell, people from the nations will be able to visit as tourists, but by and large, besides a rare exception or two, we will live in our own countries, which in my case is the United States of America…a United States devoid of Jews, synagogues, tallit gadolim, and all that, because they will only exist among the Jews in Israel.

I don’t know the answer to this one, but I think this is the central question I’m approaching. How will we Gentiles live in our own nations half a world away from Israel and King Yeshua? What will our relationship be to God?

I don’t know the answer to this one, but I think this is the central question I’m approaching. How will we Gentiles live in our own nations half a world away from Israel and King Yeshua? What will our relationship be to God?

The answer to how we’ll live in the future is the answer to my current puzzle.

As I ponder what I just wrote, I realize that even searching out Paul’s perspective on the Gentiles is a mistake. He was trying to find a way for Jews and Gentiles to co-exist in Jewish community. He never succeeded as far as I can tell. No one has succeeded since then, including in the modern Messianic Jewish movement.

But in the Messianic future, as such, Jews and Gentiles really won’t be co-existing in Jewish communal space. Jewish communal space will be the nation, the physical nation of Israel. We goys will be living every place else except in Israel. Maybe the Kingdom of Heaven will be more “bilateral” than I previously imagined.

Or have I answered my own question?