And Nobah went and captured Kenath and its dependencies, renaming it Nobah after himself.

And Nobah went and captured Kenath and its dependencies, renaming it Nobah after himself.

–Numbers 32:42 (JPS Tanakh)

Why did the Almighty include this verse in the Torah?

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch elucidates: Throughout the world powerful leaders have wanted to leave monuments to themselves through statues and buildings named after them. Kings and conquerors have even named large cities after themselves. However, names can very easily be changed and then nothing is left, as happened to Novach. (Neither Novach nor the city he named after himself are remembered to history.) The good deeds of a person and his spiritual attainments are the only true everlasting monuments.

When you view the good that you do as your eternal monument, you will feel greater motivation to accomplish as much as you can. A life of spiritual attainments is everlasting. Feel joy in every positive act you do, for it gives greater splendor to your monument!

Dvar Torah for Matot–Massei

based on Growth Through Torah by Rabbi Zelig Pliskin

as quoted by Rabbi Kalman Packouz in “Shabbat Shalom Weekly”

Aish.com

Rabbi Packouz also tells a story about the consequences of doing good.

It reminds me of the story of the father asking his son, the Boy Scout, if he did his good deed for the day. The boy says, “Sure, I helped an old lady cross the street. It took 12 of us.” “Why did it take 12 boys to help her across the street?” asks the father. Answers the son, “Because she didn’t want to cross!”

Every act of kindness has the possibility of a personal benefit. We must work to divest ourselves from our personal interest and to do kindness just to help someone.

Often, we choose to do the good deed or act of kindness that we want done for us or that we define as “good.” This is like the small boy who chooses to buy a toy he’s always wanted for a Mother’s Day gift. It would certainly seem like a kindness if he received the toy, but his mother might have other ideas about what she wants.

Forcing a “kindness” on someone who doesn’t want it is not only failing in your attempt to do good to another person, but it’s actually causing them harm. Imagine how the poor elderly woman felt in Rabbi Packouz’s story, when she found herself forced by twelve well-meaning but misguided boys, across the street. She is now where she didn’t want to be and, if she has difficulty crossing the street unaided, may not be able to easily get back home or to some place safe. And what if, in attempting to re-cross the street (without the aid of twelve “helpful” Boy Scouts this time), she is hit and injured by a car? Is that kindness?

I sometimes feel this way about sharing the gospel or the “good news” of Jesus, particularly with people who haven’t asked for such “news”. I remember the conversation that eventually led me to accept that Jesus is Messiah and Savior. I’d heard the same spiel many times before, and each time it was unwelcome and uncomfortable. I never wanted to be rude, but I also didn’t want to have to listen to someone tell me that I needed to be saved from my sins.

Fortunately, it wasn’t the spiel all by itself that resulted in my decision. A series of highly unlikely “coincidences” occurred over a period of six or more months finally resulted in getting me inside a church and then it took months and months more before I felt uncontrollably drawn (dragged kicking and screaming, metaphorically speaking) toward a life of faith and across the threshold into that life.

Almost immediately afterward, my life fell apart in more ways than I want to describe. Then, every time I thought I was starting to get a handle on what I was doing and why, another roadblock or explosion occurred. In more recent days, I tend to experience fewer explosions and more detours and frustrations on my journey.

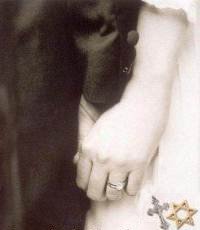

When my wife and I first married, neither one of us were religious, so her being Jewish and me being a Gentile didn’t make it seem like we were “intermarried.” There really weren’t any Jewish members of her family on our side of the country, so I never experienced Jewish in-laws. Faith and religion wasn’t an issue then as it is today.

When my wife and I first married, neither one of us were religious, so her being Jewish and me being a Gentile didn’t make it seem like we were “intermarried.” There really weren’t any Jewish members of her family on our side of the country, so I never experienced Jewish in-laws. Faith and religion wasn’t an issue then as it is today.

I’ve been a believer for over fifteen years now, and if I could find the youth pastor who first shared the “good news” of Jesus Christ with me and started this ball rolling, I don’t know if I’d shake his hand or hit him.

No, I wouldn’t hit him and I don’t regret my decision.

But if I were a secular Gentile instead of a Christian, who I am wouldn’t be such an issue for my wife as a religious Jew. There are plenty of intermarried couples who freely attend the local synagogues in my community. Certainly the Reform shul doesn’t have difficulties with intermarried Jewish members. There are even non-Jews on the synagogue’s board. And the Chabad’s mission is to bring secular or assimilated Jews back to the Torah. As part of that effort, their non-Jewish spouses are welcome within their walls.

I once told my Pastor that one of the reasons I stopped any sort of overt “Messianic” worship or lifestyle was that my wife found it embarrassing. He asked something like, “She isn’t embarrassed about you being a church-going Christian?”

Actually, I strongly suspect she is. She doesn’t invite Jewish friends over to our house. She doesn’t go to shul anymore. She hasn’t even volunteered at either synagogue in a quite a while. She and my daughter used to spend a lot of time helping the Chabad Rebbitzin with various projects.

Was it a kindness to my wife that I became a Christian? Does that seem like a good deed to her? Is it what she asked for in a husband, or is it the moral equivalent of twelve overly zealous Boy Scouts forcing a helpless old lady across a busy city street?

Someone recently said to me that love does not see religion but people do. Another person has said to me not to seek any religion but to seek an encounter with God.

I trust I speak in charity, but the lack in our pulpits is real. Milton’s terrible sentence applies to our day as accurately as it did to his: “The hungry sheep look up, and are not fed.” It is a solemn thing, and no small scandal in the Kingdom, to see God’s children starving while actually seated at the Father’s table.

from the Preface of A.W. Tozer’s book

The Pursuit of God

I would hope one thing my wife and I have in common is the pursuit of God. Our paths are quite different, but perhaps not as different as you might imagine. While I would not abandon my faith in Jesus as Messiah, I would enter into her world in a heartbeat. As awkward as it might be for me (I don’t know Hebrew and the liturgical service would present quite a learning curve), I know now that I would strive to be a good and productive member of her community for her sake. But she’s told me that she would never, ever enter mine and, for the life of her, she can’t imagine why I would want to enter hers.

So would it be a kindness to try to introduce her to my world? She wouldn’t experience it that way and in fact, quite the opposite. She would feel like I was trying to drag her kicking and screaming into a place she never wanted to go. And whenever I’ve tried to enter her world, she’s always seen me as an intruder.

Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein and many other Jewish people like him were not dragged kicking and screaming into faith in Yeshua as Messiah. They each followed the paths Hashem placed before them and by faith, they walked those paths, though it was always difficult and hazardous.

None of those Rabbis became Christians and none of them believed in “Jesus Christ.” They simply examined the Hebrew scriptures and what the church calls “the New Testament” and discovered the clues to the truth of Moshiach in their pages. If some missionary had tried to “convert” them, maybe some would have become “Christians” but Judaism would have lost great leaders and Messiah would have lost devoted Jewish disciples.

None of those Rabbis became Christians and none of them believed in “Jesus Christ.” They simply examined the Hebrew scriptures and what the church calls “the New Testament” and discovered the clues to the truth of Moshiach in their pages. If some missionary had tried to “convert” them, maybe some would have become “Christians” but Judaism would have lost great leaders and Messiah would have lost devoted Jewish disciples.

I don’t know that it is a kindness to cause a Jewish person to convert to Christianity. No, let me change that. I know it’s not a kindness. It’s not a kindness to destroy someone’s identity and purpose, especially if that identity and purpose was given to them directly by God. It is a kindness to help them on the next step on their journey, but they have to want to go. If they don’t want to start that part of the journey, you can’t force them to, even if you think it’s the best thing in the world for them. All you can do is open the door.

If they don’t go in, that doesn’t mean you’ve failed. If they don’t go in, that doesn’t mean you stop loving them. Kindness, compassion, and love, like all other things, are expressed by you and by me, but they are always from God.

God sets the course, He provides the path, He charts the journey. He does all this in love and compassion and kindness.

We can ask the elderly woman if she wants to cross the street and if she says, “no,” then we must let the answer be “no.” If the answer is “yes,” then it is a kindness to help her. If she wants to cross the street and asks for our help, we have a responsibility to be available, receptive, and then to escort her.

Kindness consists of loving people more than they deserve

-Jacqueline Schiff

God creates the street, but it is up to each person to ask for help crossing it. Then we can start walking and continue our journey.

Good Shabbos.

82 days.