Over the last decade or so, more and more scholars of the New Testament have pointed to the need to re-think the terminology we use in our analyses as well as our teaching. Several terms have been asked to retire, as Paula Fredriksen has phrased it, and leave room for new words and expressions that may help us to better grasp what was going on in the first-century Mediterranean world, a time and culture very distant from our own.

–Anders Runesson

from the beginning of his essay

“The Question of Terminology: The Architecture of Contemporary Discussions on Paul”

Paul within Judaism: Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle (Kindle Edition)

George Orwell’s famous novel 1984 demonstrates very well that when you control a people’s language, you control how they think. If a population has no word for “riot” or for “liberty,” they will be unlikely to be able to conceive of, let alone operationalize those ideas.

So the words we use in understanding Paul affect how we think of Paul, his writing, his teaching, and how we conceptualize our Christian faith. Even the term “Christian faith” summons particular thoughts and ideas that Paul may not have (and probably didn’t have) in his possession at any time in his life.

It is said that interpretation begins at translation, the words in English (or whatever other language) we use to translate Biblical Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. How we translate the Bible and what terms we use to express “Christian” ideas are part of what Runesson calls the “politics of translation.” This suggests that any attempt to disturb the status quo of how the Bible is translated now and what terms and phrases are included will encounter resistance. If you change the term “Paul the convert to Christianity” to “Paul the Jewish emissary to the Gentiles,” the accompanying image of Paul immediately and dramatically changes.

In his article, Runesson focuses on two terms in English used in Biblical translations: “Christians” (including “Christianity”) and “church.”

He further states:

It will be argued that “Christians,” “Christianity,” and “church” are politically powerful terms that are inadequate, anachronistic, and misleading when we read Paul…

These terms serve the needs of the 21st century church but in doing so, wholly misrepresent Paul the Apostle and everything he ever wrote or taught. Both modern Christianity and modern Judaism receive the same image of the Apostle from this mistaken illustration of Paul, and while the Church hails the story of a Jewish Pharisee who converted to Christianity and taught new disciples to replace the Law with Grace, Judaism reviles him for the same reasons.

In discussing “translating history,” Runesson asks if we are “colonizing the past or liberating the dead?” America is a colonial nation and as we know from our own history, and that of other such empires, one colonizes a “new world” and an indigenous people by subjugating what was there before and reforming it to resemble the colonizing nation and the colonizing people.

If we (Gentile Christianity) have done so with the past, with Paul, with the Bible, then we aren’t interpreting Paul in any accurate manner. Rather than employing exegesis, or taking our meaning of the Biblical text from the original context of that text, we are performing eisegesis or overwriting the text by inserting our own meaning anachronistically and erroneously.

I mentioned in my previous review some of the historical events surrounding men like Augustine and Luther in terms of their probable motives for rewriting Paul’s history and they aren’t all pretty. In that review, you will recall, I quoted Magnus Zetterholm as saying that it is the Christian Church that must change, that must adjust how it chooses to understand Paul, to be more historically accurate and Biblically sustainable.

Runesson states:

New insights are thus dependent on our willingness to de-familiarize ourselves with the phenomena we seek to understand…

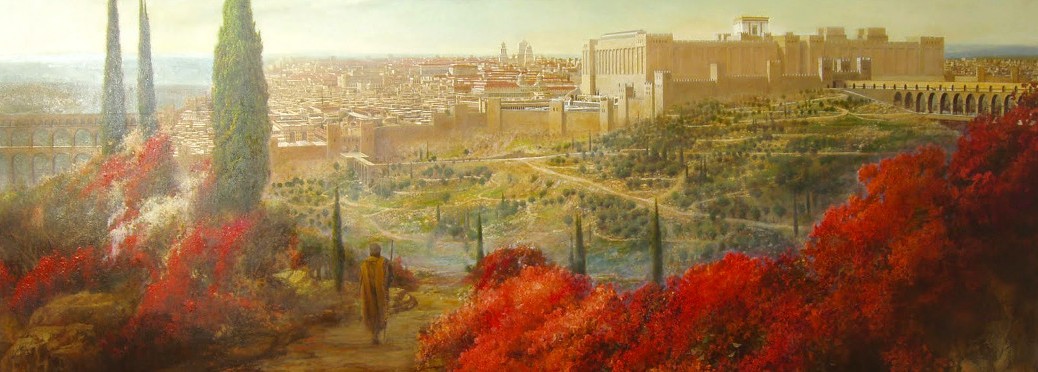

We think we know Paul. We think we know Jesus (Yeshua). We think we are intimately familiar with the late Second Temple period in Roman occupied Judea, not because we read the Bible, but because we listen to the prevailing Christian doctrine about the Bible as preached from the pulpit and taught in Sunday school class.

We don’t truly comprehend how alien that ancient world really was, how few historical facts have survived from that time and place. We want to believe that if Paul miraculously appeared in one of our Evangelical churches today, he would immediately feel at home and provide us with a sermon of unparalleled insight (assuming he spoke a language we understood). In fact, even if he understood our language, he would have absolutely no idea what was going on and probably wouldn’t even understand that we are the descendants of the Gentile disciples he taught.

We need to learn to experience Paul as someone we’ve never met. We need to learn about him from that view. We need to stop creating Paul in our own image and cease colonizing the ancient near east of the Apostolic Scriptures.

As Runesson puts it:

Reconstructing and translating history inevitably begins and ends with language. When we defamiliarize ourselves with texts and other artifacts, we engage in a process of decolonizing the past, liberating the dead from the bondage of our contemporary political identities.

This he calls the “reconstruction of silenced voices.”

So how are we going to change the “architecture of the conversation?”

Terminological edifices are built slowly over time and are not easily torn down. Now-unsustainable scholarly ideas from previous eras influence current discourses…

It might be easier for you to pick up your car with your bare hands and lift it over your head than it would be to change a Christian’s time-honored and “sacred” traditions about the words they/we use to describe Paul.

We need, therefore, to reconsider and discuss not only the conclusions we draw, but also the “architecture” within which we formulate them.

Terminology is pregnant with meaning that often goes unnoticed in the analytical process, which it nevertheless controls from within.

The minute we use a term or set of terms to describe an idea, we have shaped the meaning of that idea, even unknowingly, into something that might be completely foreign to the person who originated that concept.

When we talk about New Testament scholarship in general and Paul in particular, it has been the convention to say that one is studying (earliest) “Christianity” and/or (the early) “Christians.” Already at this point we have framed the shape and thus the likely outcome of the discussion…

Even the term “New Testament” as contrasted with another term, “Old Testament” creates a dichotomy that doesn’t necessarily exist. I’ve known intelligent, learned, well-read Christian clergy who actually believe the New Covenant (which we find in Jer. 31 and Ezek. 36) is actually synonymous with New Testament. I choose to think of the Bible as being divided into four basic parts: Torah, Prophets, Writings, and Apostolic Scriptures. None of those classifications is designed to divorce one part of the Bible from the other as the terms “Old Testament” and “New Testament” do. They simply classify different areas of emphasis for different sections of our Holy text. If we must “carve up” the Bible, let’s do it without setting one part in direct opposition to another.

Even the term “New Testament” as contrasted with another term, “Old Testament” creates a dichotomy that doesn’t necessarily exist. I’ve known intelligent, learned, well-read Christian clergy who actually believe the New Covenant (which we find in Jer. 31 and Ezek. 36) is actually synonymous with New Testament. I choose to think of the Bible as being divided into four basic parts: Torah, Prophets, Writings, and Apostolic Scriptures. None of those classifications is designed to divorce one part of the Bible from the other as the terms “Old Testament” and “New Testament” do. They simply classify different areas of emphasis for different sections of our Holy text. If we must “carve up” the Bible, let’s do it without setting one part in direct opposition to another.

Runesson asks if the earliest followers of Messiah would have recognized the “umbrella term” we’ve assigned to them: “Christianity” and their own identity as “Christians” as we comprehend the term today? Would they have understood that when they gathered to fellowship and to worship, they were going to “church?”

Christianity is a religion. But up until a couple of centuries ago or so, “religion” wasn’t a distinct entity that could be wholly separated from other societal functions. So to call the “religion” of Paul “Christianity” or even “Judaism,” as such, is to impose a modern concept on an ancient people. Although there was not one uniform practice of Judaism in the first century world (although according to Rabbi Carl Kinbar, there was a core Judaism that all branches of Judaism agreed upon and variations were then applied), if one was a Jew, one’s lifestyle included the mitzvot in devotion to God (apart from the periodic heretic or two).

Calling Paul a Christian and saying he practiced Christianity is totally anachronistic and forces modern Church concepts on an ancient Jewish Pharisee who saw himself quite differently.

Even acknowledging the existence of the Greek word “christianos” (translated into English as “Christian”) does not mean that how “christianos” was thought of and lived out nearly two-thousand years ago has very much or even anything to do with how Christians think of and live out their faith today. What would a modern Evangelical think if he took a trip in Mr. Peabody’s “Wayback Machine” and found himself in Paul’s “church” in Antioch? How would that Christian navigate through what would (in my mind) undoubtedly be a Jewish synagogue prayer service on Shabbat rather than a Sunday church fellowship?

The most natural point of departure for renewed terminological reflection around who Paul was and how he self-identified would be to speak not of “Paul the Christian” but of “Paul the Jew”; of Paul as someone who practiced “Judaism,” not “Christianity.”

Simply put, “Christianity” didn’t exist while Paul lived in the world. Paul taught about and wrote about and lived out a Judaism called “the Way,” and he applied it to his Gentile disciples as it was relevant to them as Gentiles. He himself was a Jew, a Pharisee, a devout Hebrew, dedicated to the mitzvot, the Temple, the Torah, and Hashem, God of his fathers.

If anyone else has a mind to put confidence in the flesh, I far more: circumcised the eighth day, of the nation of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; as to the Law, a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to the righteousness which is in the Law, found blameless.

–Philippians 3:4-6 (NASB)

And as Runesson says:

…that speaking of Paul as a Jew practicing a form of Judaism is a more historically plausible point of departure for interpreting his letters…

And given all that, how do we read and interpret Paul’s letters if we employ this drastically changed paradigm?

Actually, it’s harder than that.

This does not mean, of course, that we should understand “Jewish” in essentialist terms as ahistorically referring to specific characteristics completely untouched by time and culture.

And…

…the observer needs to focus on how “a society understands and represents Jews at any given time and place…”

So dropping Paul in a modern Orthodox Jewish synagogue on Shabbat might not be a particularly familiar experience for him either, though he’d have something more in common with the other Jews present than he would a Christian congregation.

So dropping Paul in a modern Orthodox Jewish synagogue on Shabbat might not be a particularly familiar experience for him either, though he’d have something more in common with the other Jews present than he would a Christian congregation.

We have to answer the question of what kind of Judaism Paul practiced. Only then can we gain a better understanding of what he was writing about in his letters. If we could only view them through his own interpretive lens or through the eyes of his immediate audience, what revelations would we see?

Runesson said that he and Mark Nanos have coined the term “Apostolic Judaism” to refer to the sort of Judaism Paul practiced and taught. How that Apostolic Judaism was lived out by Jews and by Gentiles is our mission of discovery.

Moving on to his discourse on the term “church,” Runesson brings up a point that I’ve written about on more than one occasion. The Old English word which eventually became “church” and originated in earlier Germanic languages wouldn’t be coined for many, many centuries after Paul penned letters mentioning the “Ekklesia” of Messiah. Translating the word “Ekklesia” as “Church” in our English Bibles is not only anachronistic, it is misleading and probably even dishonest.

Ekklesia, at least in Paul’s mind, was probably more closely associated to the Hebrew word “Kahal” than “Church”. It would be better, if we need to use an English word, to translate “Ekklesia” as “Assembly,” which more accurately maps to the first century Greek meaning of the term. Paul didn’t invent “Church,” either the word or the attendant concept. Later Christian Gentiles did that.

Paul never uses the word synagoge, but since ekklesia as a term was applied also to Jewish synagogue institutions at this time, it is instructive to compare how translators work with synagoge in relation to ekklesia.

In modern Bible translations and modern Christian thought, we have created a separate and opposing relationship between church and synagogue. Christians think of synagogue as the polar opposite and negative reflection of church. But this “anachronistic dividing line” is a manufactured artifact of later Church history and has nothing to do with Paul. Paul would have more closely associated Ekklesia and Synagoge in his thoughts than this thing called “church” which had no existence in his era.

Nevertheless…

Ekklesia occurs 114 times in the New Testament. The NRSV translates all but five of these with “church”…

What Runesson says next supports what I said above:

…the English translation “church” is inappropriate and misleading…

It is more accurate to say:

Paul’s use of ekklesia indicates that as the “apostle to the nations” he is inviting non-Jews to participate in specific Jewish institutional settings, where they may share with Jews the experience of living with the risen Messiah, of living “in Christ.”

Maybe that can be said to be true also of Gentiles who find themselves in fellowship within modern Messianic Jewish community. We are invited to share in a Jewish institutional setting while remaining Gentiles, and “share with Jews the experience of living with the risen Messiah.”

We can dispense with colonizing the past and instead participate in giving a voice to the dead, letting them speak to us again, letting them…letting Paul use his own voice, or as close to it as we can manage.

We can dispense with colonizing the past and instead participate in giving a voice to the dead, letting them speak to us again, letting them…letting Paul use his own voice, or as close to it as we can manage.

Runesson concludes his essay with:

The terminology used by the sources themselves invites us to understand Paul as practicing and proclaiming a minority form of Judaism that existed in the first century. Such an invitation is, however, not the end of the research project; it is its very beginning.

I’ll continue my review soon.